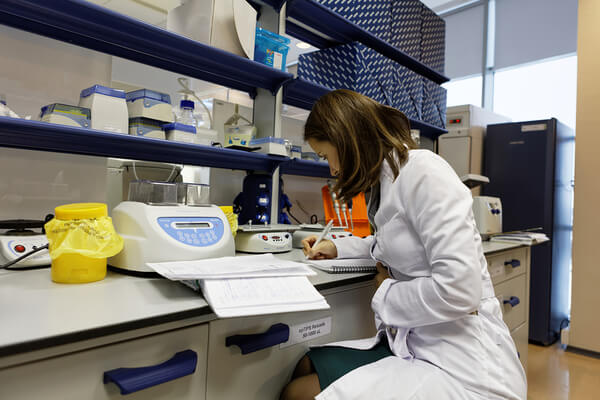

1. Introduction: Defining the Landscape of Off-Label Use and Drug Repurposing

The pharmaceutical sector is continuously seeking innovative avenues to deliver effective treatments while optimizing resource allocation. Within this pursuit, the utilization of existing drugs for new therapeutic applications has emerged as a powerful strategy. This section establishes a foundational understanding by clearly defining and distinguishing between off-label drug use and drug repurposing, tracing their historical evolution, and highlighting their growing contemporary significance.

1.1. Clear Definitions and Distinctions

Off-Label Drug Use

Off-label drug use occurs when a physician prescribes a medication that has received official approval from regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a purpose, dosage, or method of administration not explicitly listed on its approved label.1 This can involve prescribing the drug for a different disease or medical condition than its approved indication, at a dosage different from the approved range, or through an unapproved route of administration.1 For example, a tricyclic antidepressant, approved for depression, might be prescribed off-label to manage certain types of pain.1 While this practice is entirely legal for physicians, who base their decisions on their medical judgment and available scientific data, it is crucial to note that pharmaceutical companies are legally prohibited from advertising or promoting their drugs for these unapproved uses.1 Violations of these marketing restrictions can lead to substantial monetary settlements and penalties under acts like the Federal False Claims Act.6

Drug Repurposing (Repositioning/Reprofiling)

In contrast, drug repurposing, also known as drug repositioning or reprofiling, represents a deliberate, industry-driven strategic approach. It involves the systematic identification of novel therapeutic applications for existing drugs that are already approved for other indications, or even for compounds that were previously studied but failed to gain initial approval.10 This strategy is considered a core approach in drug development, aiming to accelerate the discovery process by leveraging the extensive existing pharmacological knowledge and clinical data associated with these compounds.10

Distinction

The fundamental difference between these two concepts lies in their initiator and primary objective. Off-label use is a clinical decision made by a physician for an individual patient, driven by medical judgment. Drug repurposing, however, is a strategic research and development (R&D) and commercialization endeavor undertaken by a pharmaceutical company or research institution. Its goal is to gain formal regulatory approval for a new indication, thereby officially expanding the drug’s market and securing new commercial opportunities.1

The legality and widespread nature of physician-initiated off-label use 1 inadvertently create a “real-world laboratory” for observing potential new indications for existing medications. The anecdotal or preliminary data generated from this extensive medical practice 2 can serve as a crucial initial signal for pharmaceutical companies. This pre-validated hypothesis significantly de-risks the early stages of formal drug repurposing R&D, reducing the initial investment and uncertainty for companies exploring new indications. The observation of a drug’s effectiveness in an off-label context can thus organically inform and accelerate industry R&D strategies, leading to the formal validation and commercialization of beneficial new uses.

1.2. Historical Context and Growing Significance

Historical Practice

The informal practice of physicians prescribing approved drugs for new purposes has been a part of medical practice for many years.23 Historically, many successful examples of drug repurposing arose serendipitously, stemming from unexpected observations in clinical settings or during early trials.12 A classic example is sildenafil (Viagra), which was initially developed by Pfizer for angina but unexpectedly demonstrated efficacy in treating erectile dysfunction, leading to its repurposing and subsequent blockbuster success. It later found another use in treating pulmonary arterial hypertension.12 Similarly, thalidomide, infamous for causing severe birth defects in the 1960s, was later repurposed and approved for treating leprosy and multiple myeloma, demonstrating a dramatic revitalization of a drug with a tragic past.12 Aspirin, a long-standing analgesic and antipyretic, provides another compelling example, with numerous off-label uses now considered standard care, such as for cardiovascular disease prophylaxis in high-risk patients.5

Modern Relevance

Drug repurposing has gained immense strategic importance in recent decades, primarily due to the escalating costs, protracted timelines, and high attrition rates associated with traditional de novo drug discovery.10 It offers a more streamlined and efficient pathway to clinical translation, bypassing many early-stage development hurdles.12 The urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic further underscored its value, propelling hundreds of clinical trials aimed at repurposing existing drugs to combat the virus, thereby demonstrating its critical role as a rapid response mechanism for global health crises.13

The historical reliance on accidental discoveries for drug repurposing 12 is progressively being supplanted by systematic, data-driven approaches.15 This evolution, driven by the integration of “big data” methodologies and the increasing sophistication of artificial intelligence (AI) and omics technologies 15, signifies a maturation of the drug repurposing field. This progression implies that future market domination will increasingly depend on predictable and strategic scientific endeavors rather than mere chance, necessitating significant investment in advanced analytical capabilities. Companies that fail to adopt advanced computational and data analytics may find themselves at a significant competitive disadvantage as the process becomes more predictable and less reliant on serendipitous findings.

Table 1: Key Differences: Off-Label Use vs. Drug Repurposing

| Aspect | Off-Label Use | Drug Repurposing |

| Definition | Physician prescribes for unapproved use/dose/route 1 | Industry identifies new therapeutic uses for existing drugs 10 |

| Initiator | Physician | Pharmaceutical company/research institution |

| Legality (for initiator) | Legal for physician 1 | Legal (as R&D strategy) |

| Legality (for manufacturer promotion) | Illegal for manufacturer to promote 1 | Legal (if new indication is formally approved) |

| Regulatory Oversight | FDA does not regulate practice of medicine 1 | FDA/EMA regulatory approval process 34 |

| Primary Goal | Patient benefit based on medical judgment 1 | Formal market expansion, addressing unmet needs, lifecycle management 11 |

| Required Evidence (for use) | Physician’s clinical judgment, often limited data 2 | Rigorous clinical trials 34 |

| Typical Risk Profile | Higher risk of adverse effects due to limited testing for specific use 3 | Lower risk than de novo (known safety profile) 10 |

| Commercial Incentive for Manufacturer | Indirect (increased sales, but no formal market expansion incentive) 7 | Direct (new patents, market exclusivity, increased revenue) 15 |

2. The Strategic Imperative: Why Drug Repurposing Offers a Competitive Edge

In an increasingly competitive pharmaceutical landscape, drug repurposing stands out as a powerful strategic tool. Its inherent advantages in terms of cost, time, and risk mitigation, coupled with its ability to address critical unmet medical needs and enhance portfolio value, position it as a key driver for market domination.

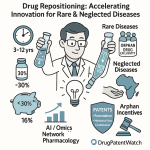

2.1. Economic Advantages: Reduced Costs and Accelerated Timelines

Drug repurposing offers compelling financial and temporal efficiencies compared to traditional de novo drug development. The overall development expenses for repurposed drugs are estimated to be 50-60% lower, typically around $300 million, a stark contrast to the $2-3 billion often required to bring a novel drug to market.17 This substantial cost reduction is primarily attributed to the ability to bypass early, resource-intensive stages such as preclinical compound discovery and Phase I safety studies, as safety and toxicity data for existing compounds are usually already available.10 In some instances, the well-established safety profile of a repurposed drug may even allow for direct progression to Phase II clinical studies focused on efficacy for the new indication, further streamlining the process.17

Beyond cost savings, repurposing significantly accelerates development timelines. It can shorten the typical drug development process by an average of 5 to 7 years, with approval times ranging from 3 to 12 years, considerably faster than the 10-17 years for new chemical entities.12 This expedited path to market provides quicker access to much-needed drugs for patients, enhancing a company’s responsiveness to market demands.22

Furthermore, repurposed drugs exhibit a remarkably higher approval rate compared to novel compounds. While only about 10% of new drug applications typically gain market approval, approximately 30% of repurposed drugs successfully navigate the regulatory pathway.16 This reduced risk of failure stems directly from their established safety and toxicity profiles, which have already been de-risked in prior development efforts.10

The synergistic combination of significantly reduced R&D costs, accelerated development timelines, and remarkably higher approval rates fundamentally alters the risk-reward equation for pharmaceutical companies, making it far more favorable.16 This is not merely about achieving cost savings; it is about optimizing the return on investment (ROI) and fostering a more predictable and sustainable pipeline. The inherent unpredictability and high failure rates associated with traditional

de novo drug discovery are mitigated, providing a more reliable pathway for capital deployment and market entry.

2.2. Addressing Unmet Medical Needs and Expanding Patient Access

Drug repurposing plays a crucial role in addressing areas of significant medical need that are often overlooked by traditional drug development models.

Rare and Neglected Diseases

It holds particular value for rare and neglected diseases, where conventional de novo drug development is frequently financially unviable due to limited patient populations and lower projected market returns.10 Repurposing offers a more economically viable pathway to provide new treatments for these underserved patient groups, transforming what might otherwise be commercially unattractive endeavors into feasible projects.11

Emerging Health Crises

The rapid response capability inherent in drug repurposing was vividly demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hundreds of clinical trials were swiftly initiated to investigate existing drugs for new uses to combat the virus, highlighting its critical role as an agile mechanism for addressing pressing public health threats.13 This ability to quickly pivot and test existing compounds in new crisis situations underscores its strategic importance beyond typical market considerations.

Vulnerable Populations

Off-label use, which often precedes formal repurposing efforts, is common in patient populations with limited approved treatment options, such as cancer patients (approximately half of all anticancer drugs are prescribed off-label) 1 and children (where lack of pediatric indications often leads to off-label prescribing).9 Formal repurposing can legitimize and standardize these uses, ensuring safer, evidence-based treatments for these “therapeutic orphans” who might otherwise lack approved therapeutic options.7

2.3. Lifecycle Management and Portfolio Enhancement

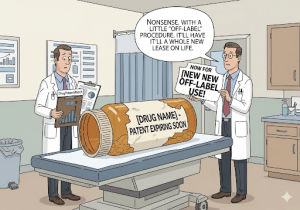

Drug repurposing is a powerful strategy for optimizing a product’s lifecycle and enhancing a company’s overall portfolio.

Extending Patent Life and Market Share

It serves as a pivotal strategy for lifecycle management, enabling pharmaceutical and biotech companies to extend the commercial lifespan of their products. This is achieved by applying existing drugs to adjacent diseases or new patient populations beyond their original primary indication.15 By securing new method-of-use patents or leveraging orphan drug designations, companies can obtain crucial market exclusivity, significantly increasing market share and overall revenue potential.15

Rejuvenating Portfolios

This strategic maneuver offers an effective means to breathe new life into mature drug products.19 By identifying new applications, companies can transform dormant assets into revenue-generating products, thereby contributing to sustainable growth and enhancing the overall value and resilience of their pipeline.16

The demonstrated economic viability of drug repurposing for rare and neglected diseases 10 signals a significant strategic shift away from an exclusive, high-risk focus on “blockbuster” drugs for large patient populations. Traditionally, the high costs of

de novo development necessitated targeting vast markets to recoup investment. However, the lower development costs associated with repurposed drugs make smaller patient populations, such as those with rare diseases, financially attractive.11 This enables companies to pursue drug candidates that might have been abandoned due to insufficient market size, fostering a more resilient business model that is less dependent on a few high-revenue drugs. This diversification also aligns with enhanced social responsibility by addressing previously unmet medical needs.

Table 2: Economic Advantages of Drug Repurposing vs. De Novo Drug Development

| Metric | De Novo Drug Development | Drug Repurposing |

| Average Development Cost | $2-3 Billion 17 | ~$300 Million (50-60% lower) 17 |

| Average Development Time | 10-17 Years 17 | 3-12 Years (5-7 years shorter) 17 |

| Phase I to Approval Success Rate | <10% 16 | ~30% 16 |

| Risk of Failure (Safety/Toxicity) | High (~45% due to safety/toxicity) 22 | Reduced (known safety profile) 10 |

| Ability to Address Rare Diseases | Financially Challenging 10 | Economically Viable 11 |

3. Scientific Foundations: Identifying Repurposing Opportunities

The success of drug repurposing hinges on a deep understanding of underlying biological mechanisms and the application of sophisticated discovery methodologies. This section explores the scientific principles that guide the identification of new therapeutic uses and the modern computational and experimental tools that facilitate this process.

3.1. Underlying Scientific Principles

Drug Pleiotropy

Drug pleiotropy is a fundamental phenomenon describing how genetic variants or genes can influence multiple distinct traits or phenotypes.43 In the context of drug repurposing, this implies that a drug designed to target a specific gene or pathway for one disease might inadvertently or intentionally affect other traits or diseases that share a common underlying genetic architecture.43 This dual effect can lead to both novel therapeutic opportunities and, if undesirable, potential side effects.43 Understanding pleiotropic effects allows researchers to predict potential new indications by tracing shared genetic associations across different conditions.

Polypharmacology (Multi-targeting)

Polypharmacology refers to the ability of a single drug molecule to interact with multiple known biological targets, either within a single disease pathway or across multiple distinct disease pathways.14 While unintended polypharmacology can sometimes lead to off-target side effects, beneficial multi-target activities are highly sought after in drug repurposing, as they can offer potentially higher therapeutic efficacy and synergistic effects.14 The traditional “one drug, one target” philosophy in drug design has evolved towards embracing “one drug, multiple targets” as a modern drug discovery paradigm, recognizing that complex diseases often require modulation of multiple pathways.45 Aspirin, for instance, is a classic example of a polypharmacological drug, with its diverse effects extending far beyond its original analgesic properties.45

Shared Disease Mechanisms

A growing understanding in network medicine reveals that diseases, even those that appear clinically disparate, can share similar underlying biological defects, signaling pathways, or molecular mechanisms.11 Identifying these commonalities is crucial for repurposing, as it allows for the application of drugs that modulate these shared mechanisms to new indications.11 For example, a drug developed to treat one type of cancer might be effective against another if they share common pathways of uncontrolled cell growth.48 Tools such as disease networks and knowledge graphs are instrumental in uncovering these hidden connections and relationships among diseases, genes, and molecular processes.46

3.2. Modern Discovery Methodologies

Pharmaceutical organizations typically employ a range of systematic strategies to identify drug repurposing candidates, moving beyond serendipitous discoveries.

Phenotypic Screening

This method involves observing the effects of drugs on cells or whole organisms without necessarily requiring prior knowledge of the specific molecular target or mechanism of action.49 It has historically been successful in discovering many approved molecules and biologics, often leading to serendipitous discoveries of new uses. This approach offers a high chance of application across various drugs or conditions because it focuses on observable outcomes rather than predefined targets.49

Target-Based Methods

This strategy necessitates specific knowledge about the drug targets, such as their 3D protein structures, and involves systematically screening drugs for their interaction with a particular protein or biomarker of interest.49 This can be achieved through both

in vitro and in vivo high-throughput screening (HTS/HCS) or in silico screening methods like ligand-based docking. By directly linking drugs to known disease mechanisms, this approach significantly improves the chances of successful drug discovery, as it offers a more directed path to finding therapeutically beneficial compounds.49

Knowledge-Based Methods

These methods leverage existing, vast repositories of information about drugs, diseases, and their interactions, employing bioinformatics or cheminformatics approaches.49 This includes data from drug-target networks, chemical structures of targets and drugs, clinical trial information, FDA approval labels, and signaling or metabolic pathways. By integrating this wealth of known data, these methods are designed to predict unknown mechanisms, novel drug targets, and obscure drug-drug similarities, thereby improving prediction accuracy and uncovering connections that might not be obvious through other means.49

Signature-Based Methods

This advanced approach utilizes gene signatures derived from disease omics data (e.g., genomics, proteomics), with or without treatment, to uncover unknown off-target or disease mechanisms.49 Publicly available databases like NCBI-GEO are critical resources for accessing such genomics data. These methods are powerful in identifying molecular-level mechanisms, such as significantly changed genes, through computational analyses, providing a deeper understanding of a drug’s effects at a systems level.49

Disease-Centric, Drug-Centric, Target-Centric Approaches

Pharmaceutical organizations typically employ one of these three systematic strategies in their repurposing efforts.48 The

disease-centric approach evaluates existing medications to find those that can address a specific disease by targeting homologous underlying biological mechanisms. The drug-centric approach expands the application of an existing drug to a new indication, often initiated by observing existing off-label uses. The target-centric approach matches a new indication, for which no treatment exists, with an established drug and its known molecular target, even if the old and new indications differ significantly.48 The disease-centric method currently holds the largest market share in drug repurposing.50

The effectiveness of modern drug repurposing is not merely a sum of its parts; it stems from the synergistic integration of a deep understanding of scientific principles like drug pleiotropy and polypharmacology with advanced computational and experimental methodologies.14 For instance, identifying a pleiotropic effect of a drug 44 can be systematically explored and validated using signature-based methods 49 or knowledge graphs 48 to uncover new therapeutic applications. This moves beyond the accidental discoveries that characterized early repurposing efforts.15 The most promising candidates often emerge from a holistic strategy where theoretical understanding, such as a drug’s multi-target activity, guides the application of advanced computational and experimental tools. This synergy provides a more robust and predictable pathway to identifying viable candidates.

3.3. The Transformative Role of AI and Bioinformatics

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and bioinformatics has profoundly transformed the drug repurposing landscape, making it a highly data-driven and accelerated process.

Accelerated Identification

AI algorithms and advanced bioinformatics tools are systematically employed to identify and predict interactions between drugs and protein targets.18

In silico drug repositioning, powered by these technologies, offers significant advantages in terms of speed and reduced costs, allowing for rapid screening of vast drug libraries.49

Data Integration and Analysis

AI and machine learning are revolutionizing drug repurposing by enabling more precise and rapid identification of new therapeutic uses. This is achieved through the sophisticated integration and analysis of diverse data sources, including genomics, proteomics, and real-world data.12 Tools like knowledge graphs organize complex biological data into networks, allowing researchers to quickly identify, visualize, and analyze direct and indirect relationships between biological concepts and molecular classes.48 Graph neural networks (GNNs), a form of deep learning, can process these rich data structures to predict drug-target interactions and identify possible therapeutics for new indications.48

Competitive Intelligence

Natural Language Processing (NLP), a subfield of AI, is becoming indispensable for analyzing vast amounts of unstructured textual data from scientific publications, patents, clinical trial reports, and market intelligence sources.52 By automating knowledge extraction from these diverse sources, NLP enables researchers and pharmaceutical strategists to identify emerging therapeutic targets, track competitor pipelines, and uncover novel drug-repurposing opportunities with unprecedented speed and accuracy.52 Platforms like DrugPatentWatch and Cortellis leverage these capabilities to provide comprehensive business intelligence, including patent data, clinical trial progress, and regulatory information, aiding in strategic decision-making and market forecasting.55

The increasing and sophisticated reliance on AI and big data in identifying drug repurposing candidates 18 fundamentally transforms drug repurposing from a purely scientific pursuit into a critical competitive battleground. If AI can process vast, disparate datasets and identify non-obvious connections with greater speed and accuracy 17, it directly impacts the efficiency and success rate of identifying repurposing opportunities. This capability becomes a key differentiator, making investment in advanced AI not just an R&D enhancement but a strategic imperative for achieving and maintaining market leadership.

Table 3: Strategic Approaches to Identifying Repurposing Candidates

| Approach Type | Description | Key Advantage(s) | Data Sources/Tools |

| Phenotypic Screening | Observing drug effects on cells/organisms without knowing specific molecular target. | Identifies new compounds based on observed benefits; high chance of application across drugs/conditions; serendipitous discoveries. | Cell-based assays, in vitro and in vivo models.49 |

| Target-Based Methods | Systematically screening drugs for interaction with a specific protein or biomarker. | Direct link to disease mechanism; improved chances of finding therapeutically beneficial compounds. | 3D protein structures, HTS/HCS, in silico screening (ligand-based docking).49 |

| Knowledge-Based Methods | Leveraging existing information about drugs, diseases, and interactions using bioinformatics/cheminformatics. | Predicts unknown mechanisms, novel targets, obscure drug-drug similarities; improves prediction accuracy. | Drug-target networks, chemical structures, clinical trial data, FDA labels, signaling pathways.49 |

| Signature-Based Methods | Utilizing gene signatures from disease omics data to uncover off-target or disease mechanisms. | Identifies molecular-level mechanisms (e.g., changed genes); uncovers unknown mechanisms of action. | Public databases (NCBI-GEO, SRA, CMAP, CCLE), computational analyses.49 |

| Disease-Centric | Evaluates existing medications to address a specific disease by targeting homologous biological mechanisms. | Addresses diseases with unmet or partially effective treatments; valuable for rare diseases. | Disease models, pathway analysis, scientific literature, knowledge graphs.48 |

| Drug-Centric | Expands the application of an existing drug to a new indication. | Leverages known safety/efficacy profiles; often initiated by observing off-label uses. | Off-label use data, investigational/abandoned drug reviews, patent expiry analysis.48 |

| Target-Centric | Matches a new indication with an established drug and its known molecular target. | Investigates specific molecular targets implicated in disease pathology; useful for rare diseases. | Molecular target databases, drug-target interaction data.48 |

4. Navigating the Regulatory Maze: Approvals and Compliance

Successfully bringing a repurposed drug to market requires meticulous navigation of complex regulatory frameworks. This section outlines the pathways for new indication approvals by leading agencies and clarifies the critical distinction between permissible physician discretion and prohibited manufacturer promotion of off-label uses.

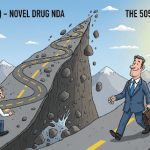

4.1. Regulatory Pathways for New Indication Approvals (FDA & EMA)

FDA Process

The FDA’s drug approval process is inherently rigorous, designed to establish both the safety and efficacy of a drug for a specific indication.1 This multi-step process commences with preclinical testing, followed by three phases of clinical trials: Phase I (safety in small groups), Phase II (effectiveness and optimal dosing in larger patient groups), and Phase III (substantial evidence of efficacy and safety in hundreds to thousands of patients).34 Upon successful completion, a New Drug Application (NDA) is submitted, containing extensive data from all testing phases, which the FDA meticulously reviews to ensure that the benefits outweigh any potential risks.34

For repurposed drugs, their pre-existing, well-established safety profiles can often streamline this process, potentially allowing for abbreviated clinical development paths.10 The 505(b)(2) pathway, in particular, is a crucial route that permits reliance on existing data from previously approved products, including published literature and the FDA’s prior findings on safety, significantly shortening the regulatory process for new indications.20 This pathway acknowledges the inherent de-risking of compounds with known safety profiles.

EMA Process

In the European Union, pharmaceutical companies submit a single marketing authorization application to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) under the centralized procedure. If approved, this authorization is valid across all EU and European Economic Area (EEA) countries.36 The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) conducts a thorough scientific assessment of the application, evaluating safety, quality, and efficacy standards based on submitted data.36 Similar to the FDA, repurposed drugs can benefit from expedited pathways such as Orphan Drug Designation (for rare diseases), Fast Track, and Breakthrough Therapy designations, especially when addressing unmet medical needs.20 The EMA also offers a Hybrid Regulatory Pathway that allows the submission of previously generated clinical data to support new indications, further expediting development.39

Challenges in Formal Approval

Despite the inherent advantages of repurposing, obtaining formal regulatory approval for new indications for existing drugs requires substantial financial resources and specialized regulatory expertise.64 A significant challenge arises because companies rarely pursue new indications for drugs that have been generic for a long time, primarily due to commercial disincentives related to recouping investment.64 The cost of conducting confirmatory clinical trials, even if abbreviated, can outweigh the potential return on investment, particularly for off-patent compounds. Furthermore, regulators currently lack the authority to unilaterally add new efficacy indications to product labeling without a formal application from a sponsor 64, placing the onus and financial burden squarely on the industry.

4.2. Regulations on Off-Label Promotion vs. Physician Discretion

Manufacturer Prohibition

It is strictly illegal for pharmaceutical companies to advertise or promote their drugs for off-label uses.1 This prohibition is a cornerstone of regulatory oversight, designed to prevent manufacturers from circumventing the rigorous FDA approval process for new indications.3 Violations of these regulations can lead to severe criminal and civil penalties, including multi-billion dollar fines, corporate integrity agreements, deferred prosecution agreements, and even jail time for company executives.6 Enforcement is often pursued under statutes like the Federal False Claims Act, with penalties including up to three times the amount of damages plus significant per-claim fines.6 Numerous historical examples, such as the settlements involving Neurontin, Serostim, and Zyprexa, underscore the severe consequences of off-label promotion.66

Physician Discretion

In contrast, once a drug has received FDA approval for at least one indication, physicians are legally free to prescribe it for any purpose they deem medically appropriate, based on their clinical judgment and available scientific evidence.1 This is a critical distinction, as regulatory bodies like the FDA regulate drugs and their labeling, but not the practice of medicine itself.1 Off-label prescribing is a common practice, accounting for an estimated 10-20% of all prescriptions, and significantly higher in specialized fields like oncology (56% of prescriptions) or in pediatric populations where approved options are limited.9 Physicians often resort to off-label use when approved treatments fail or when an unmet medical need exists.3

Ethical Considerations of Informed Consent

The practice of off-label prescribing introduces complex ethical considerations, particularly regarding informed consent. Patients might not be fully aware that the medication they are receiving is being prescribed for an unapproved use, which means they may not completely grasp the potential risks and benefits associated with that specific off-label application.3 This can undermine the fundamental principle of informed consent, which requires providing patients with all necessary information about a treatment, including its approved uses, potential benefits, and potential risks, and then obtaining their voluntary agreement.3 While explicit written consent is required for experimental or research uses, it is generally not mandated for off-label clinical use, leading to a debate among ethicists and legal scholars.70 Some argue that off-label use, especially when scientific support is limited, should be considered experimental, thus requiring explicit consent.70 Others contend that informing patients of the off-label status might “confound patient decision making by diverting attention to medically irrelevant information”.70 Despite this ambiguity, healthcare providers have a crucial responsibility to fully inform patients when a medication is being prescribed off-label and to obtain their consent before proceeding.3

The delicate balance between allowing physician autonomy for patient benefit and preventing exploitative manufacturer promotion is a constant regulatory challenge. While physicians have the legal right to prescribe off-label based on their medical judgment, manufacturers are strictly forbidden from promoting these uses. This highlights the ethical imperative for transparent communication with patients regarding off-label status, despite current legal ambiguities. Upholding patient autonomy and trust in the medical relationship necessitates clear disclosure of the unapproved nature of the use, the supporting evidence (or lack thereof), and potential risks and benefits.3

A significant barrier to market access and commercial viability for both off-label and formally repurposed drugs stems from reimbursement policies. Insurers often consider off-label use to be “experimental” or “investigational,” leading to denials of coverage, even when there is scientific evidence supporting the use.1 While laws like the Cancer Treatment Act of 1993 and updated Medicare rules in 2008 have expanded coverage for medically appropriate off-label cancer therapies, particularly if supported by recognized compendia or peer-reviewed literature 1, challenges persist. Many off-label uses, especially for rare diseases or those not listed in specific compendia (e.g., Pegasys for MPNs), continue to face denials.40 This necessitates strategic engagement with payers and proactive efforts by manufacturers to secure compendia listings or formal new indication approvals to ensure broad reimbursement and market uptake.

5. Commercialization Strategies for Market Domination

Achieving market domination through drug repurposing requires a sophisticated commercialization strategy that extends beyond scientific discovery and regulatory approval. This involves robust intellectual property protection, astute pricing and reimbursement models, comprehensive competitive intelligence, and strategic engagement with key opinion leaders.

5.1. Intellectual Property (IP) Protection and Patent Strategies

Intellectual property (IP) protection is paramount for maximizing the profitability and securing market exclusivity for repurposed drugs.15 While the original compound may no longer be patentable (due to patent expiration), several avenues exist for innovators to seek IP protection for their repurposing efforts:

- Method-of-Use Patents: These patents protect the specific method by which a known compound is used to treat a new therapeutic indication.19 This is often the “bread and butter” of drug repurposing patents.

- Formulation Patents: Novel formulations or delivery methods for existing drugs can be patented, offering new ways to administer a drug that might improve its safety, efficacy, or patient convenience (e.g., nasal delivery for naloxone).19

- Combination Patents: New combinations of known drugs may also be eligible for patent protection, especially if they demonstrate synergistic effects for a new indication.20

Despite these opportunities, patenting repurposed drugs is not without its challenges. Prior art (existing publications or patents) can limit the scope of protection, and demonstrating non-obviousness for a new use of a known compound can be difficult.17 Furthermore, if the original drug’s patent has already expired, securing broad and long-lasting exclusivity becomes more challenging, as competitors can introduce generic versions.17 This can lead to accusations of “evergreening”—a practice where companies attempt to extend patent protection through minor modifications or new uses, often facing scrutiny over their validity.19

To incentivize repurposing, particularly for rare diseases, regulatory bodies offer programs like Orphan Drug Designation. This provides benefits such as tax credits, grant funding, and extended periods of market exclusivity (e.g., seven years in the US).19 Additionally,

Patent Term Extensions may be granted by the FDA to compensate for time lost during regulatory review, allowing companies to maximize their return on investment.19

5.2. Pricing and Reimbursement Strategies

Effective pricing and reimbursement strategies are crucial for the commercial success of repurposed drugs, especially given the unique challenges they face.

Pricing Models

Pharmaceutical companies can employ various pricing models for repurposed drugs:

- Value-Based Pricing: This approach links the drug’s price to its perceived effectiveness and the clinical benefits it offers, particularly for repurposed drugs addressing high unmet medical needs or offering significant therapeutic advantages (e.g., improved patient convenience, different administration routes).15

- Cost-Plus Pricing: A straightforward method that adds a predetermined profit margin to production and R&D costs, often favored by generic manufacturers.15

- Competitive-Based Pricing: Setting prices based on competitors’ pricing for similar treatments, which for repurposed drugs might involve pricing against existing therapies for the new indication.15

Reimbursement Challenges

A significant hurdle for repurposed drugs, particularly those used off-label or those that are off-patent, is obtaining reimbursement. Insurance companies often consider off-label drug use to be “experimental” or “investigational,” leading to denials of coverage.1 This perception can persist even when substantial scientific evidence supports the off-label use.

While the Cancer Treatment Act of 1993 and updated Medicare rules (2008) have expanded coverage for medically appropriate off-label cancer therapies, especially if supported by recognized compendia or peer-reviewed literature 1, challenges remain. Many off-label uses, particularly for rare diseases or those not listed in specific compendia (e.g., Pegasys for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms), continue to face insurance denials.40 This necessitates strategic engagement with payers and proactive efforts by manufacturers to secure compendia listings or formal new indication approvals to ensure broad reimbursement and market uptake.

The impact of reformulation and changes in administration routes can significantly influence pricing and reimbursement. For instance, a change to a hospital administration setting can lead to a substantial price increase.15 New formulations adapted for different administration routes (e.g., subcutaneous or oral) can also be sufficient to obtain new patents, further influencing pricing potential and justifying a higher price point to payers.15

IP protection alone is insufficient for successful commercialization; a holistic strategy that aligns IP, regulatory approvals, and reimbursement pathways is essential. The commercial viability of a repurposed drug is heavily influenced by the ability to secure new IP, navigate abbreviated regulatory pathways, and, critically, obtain favorable reimbursement. This requires early engagement with payers to understand their evidence requirements and to design clinical trials that generate the specific data needed to demonstrate the value of the repurposed drug for the new indication.1 Without a clear path to reimbursement, even a scientifically sound and approved repurposed drug may struggle to gain market access and achieve commercial success.

5.3. Competitive Intelligence and Market Positioning

In the dynamic pharmaceutical industry, robust competitive intelligence (CI) is indispensable for identifying repurposing opportunities and effectively positioning new products. CI involves the systematic collection, analysis, and application of data about competitors, market trends, and regulatory changes to inform strategic decision-making.55

Key areas of CI relevant to drug repurposing include:

- Market Intelligence: Understanding global market trends, patient demographics, and regulatory landscapes to identify emerging therapeutic areas and shifts in treatment guidelines.55

- Pipeline Intelligence: Tracking competitor drug pipelines, monitoring clinical trial progress, analyzing R&D investments, and assessing the probability of regulatory approvals for new indications.55

- Regulatory & Policy Intelligence: Staying abreast of FDA, EMA, and other global regulatory bodies’ decisions, changes in pricing and reimbursement policies, and new market access barriers.55

- Product & Portfolio Intelligence: Assessing competitor product lifecycles, analyzing generic/biosimilar threats, and understanding launch sequencing strategies to optimize portfolio management.55

The integration of patent data, scientific literature, and real-world evidence (RWE) is crucial for comprehensive CI in drug repurposing. Advanced analytics, including AI and Natural Language Processing (NLP), are transforming this process. NLP tools can analyze vast amounts of unstructured textual data from scientific publications, patents, clinical trial reports, and market intelligence sources to extract actionable insights.52 This enables researchers and strategists to identify emerging therapeutic targets, track competitor pipelines, and uncover novel drug-repurposing opportunities with unprecedented speed and accuracy.52

RWE, derived from sources like electronic health records (EHRs) and claims data, provides valuable insights into the actual patterns of drug treatment and outcomes in real-world settings, complementing traditional clinical trial data.53 Platforms like Cortellis and DrugPatentWatch integrate these diverse data sources—including over 589,000 patents, 709,000+ drugs, and extensive scientific literature—to provide a holistic view of the competitive landscape.57 This allows companies to make informed go/no-go decisions, benchmark their drug candidates against competitors, and refine their market positioning for repurposed drugs.57

Integrating diverse data sources (patent, scientific literature, RWE) through advanced analytics (AI/NLP) provides a comprehensive view of the competitive landscape, enabling proactive strategic decisions. This data-driven approach allows companies to identify emerging opportunities, refine their market positioning for repurposed drugs, and anticipate competitor movements, thereby fostering a significant competitive advantage.17

5.4. Medical Education and Key Opinion Leader (KOL) Engagement

Formal regulatory approval for a repurposed drug is a critical milestone, but it is only the first step towards widespread market adoption. Effective commercialization requires robust medical education and strategic engagement with Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs). KOLs are highly knowledgeable experts in specific therapeutic areas who possess significant influence among healthcare professionals (HCPs) and within the broader medical community.75 Their status is often derived from extensive clinical experience, research publications, participation in clinical trials, speaking engagements at conferences, and leadership roles in professional organizations.75

KOLs play a multifaceted role in the commercialization of on-label repurposed drugs:

- Advising R&D: They provide invaluable guidance during the research and development process for new treatments, including those being repurposed.76

- Clinical Trial Participation: Their involvement in clinical trials lends credibility and helps generate robust data for new indications.76

- Effective Market Education: KOL mapping helps pharmaceutical teams identify respected experts who can educate the market about a new drug or disease. Engaging credible KOLs early ensures that when a product launches, there are knowledgeable advocates who trust the science and can influence their peers.75

- Influence Networks: KOL mapping goes beyond simple identification by uncovering relationships and networks among HCPs. Understanding these networks allows companies to leverage KOLs to amplify messages through peer-to-peer channels, ensuring wider dissemination of information about the new on-label indication.75

- Targeted Resource Allocation: By identifying high-potential prescribers and influencers, KOL mapping enables commercial teams to prioritize their educational and promotional efforts, increasing efficiency and return on investment.75

- Faster Uptake at Launch: Early KOL engagement can build disease awareness or guideline support that trickles down to frontline HCPs, setting the stage for rapid uptake once the repurposed product receives formal approval.75

Formal approval for a repurposed drug is only the initial step; effective commercialization requires robust medical education and KOL engagement to drive adoption and overcome prescriber inertia. Given the historical context where physicians may already be using the drug off-label, educating them on the new on-label indication, its supporting evidence, and any refined formulations or dosing is crucial to transition from informal use to standardized, reimbursed practice. This strategic imperative ensures that the scientific and regulatory investments translate into tangible market success.75

6. Risks and Challenges: Mitigating Obstacles to Market Domination

While drug repurposing offers significant opportunities, it is not without its complexities and risks. Navigating these challenges effectively is crucial for sustainable market success and patient safety.

6.1. Patient Safety and Ethical Considerations

Risks of Off-Label Use

The widespread nature of off-label drug use, while legal for physicians, carries inherent risks for patients. Unless carefully undertaken and supported by robust scientific data, off-label use can expose patients to elevated risks without proven benefits, or possibly no benefit at all.3 This practice can inadvertently undermine the important safety mission of regulatory bodies like the FDA, which approves drugs only for uses demonstrated to be safe and effective through rigorous testing.7 Furthermore, the prevalence of off-label use may reduce the motivation for pharmaceutical companies to invest in expensive clinical studies to obtain formal approval for new uses, meaning the safety and risks of these uses remain unstudied.7 Studies indicate a higher likelihood of adverse effects associated with off-label drug use, with one study finding a 44% overall higher likelihood in adults.7 There are well-documented examples of serious harms and even fatalities, such as the “fen-phen” combination, which caused significant lung and heart damage.7 Of grave concern is that off-label use frequently occurs among very vulnerable patient groups, including those with mental health disorders, the elderly, pregnant women, and pediatric patients, who are historically under-represented in clinical research, making them “therapeutic orphans” with limited evidence-based treatment options.7

Ethical Dilemmas

Beyond safety, off-label prescribing presents significant ethical dilemmas, particularly regarding informed consent. Patients might not be fully aware that the medication they are receiving is for an unapproved use, potentially leading to a lack of complete understanding of associated risks and benefits.3 This undermines the fundamental principle of informed consent, which mandates full disclosure and voluntary agreement.3 While some argue that off-label status is a regulatory rather than a medical risk, and that discussing it might “confound patient decision making” 70, the ethical imperative for transparency remains. The potential for exploitation also arises when pharmaceutical companies promote products for off-label uses primarily to increase sales, even without strong scientific evidence, which can endanger patients and compromise healthcare system integrity.3

6.2. Legal and Regulatory Hurdles

Off-Label Promotion Penalties

As previously discussed, pharmaceutical companies face severe criminal and civil penalties for promoting medical devices and drugs for uses not approved by regulatory bodies.6 The Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) strictly forbids this practice, leading to billions of dollars in fines, corporate integrity agreements, and even jail time for executives in numerous high-profile cases.6 Companies must implement robust risk management strategies to avoid any actions that could be interpreted as off-label promotion, even when legally profiting from prevalent off-label uses.41

Data Exclusivity and IP Limitations

Despite expedited regulatory pathways, data exclusivity laws can prevent other parties from accessing an approved product’s data for a specified period, potentially delaying the approval of reformulated repurposed drugs by up to 8 years in Europe and 3 years in the US.39 This necessitates reliance on preclinical and clinical publications, which may not always provide the complete picture.39 Furthermore, securing strong IP for repurposed drugs faces challenges from prior art, the difficulty of demonstrating non-obviousness for new uses of known compounds, and the expiration of original patents, which can limit market exclusivity.17

Resource Intensity of Approval

Even with the promise of faster and cheaper development, obtaining formal approval for new indications for repurposed drugs still requires substantial financial resources and specialized regulatory expertise.64 Challenges include defining appropriate inclusion/exclusion criteria for patient populations, isolating drug effects in combination therapies, and choosing the right primary endpoints in clinical trials.77 The process of appropriately describing available data to support a regulatory application and outlining the benefit-risk balance can be resource-intensive for both regulators and researchers.77

6.3. Market Acceptance and Reimbursement Complexities

Payer Skepticism

A significant obstacle to the commercial viability of repurposed drugs is payer skepticism. Insurance companies and managed care organizations often label off-label or newly repurposed uses as “experimental” or “investigational,” leading to denials of coverage.1 This perception can persist even when compelling scientific evidence supports the new use.

Compendia Limitations

While the Fee-for-Service Medicare program and some insurers recognize published compendia as authoritative references for medically accepted off-label uses, the coverage within these compendia is often limited.40 For instance, despite its increasing use and efficacy, Pegasys for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms is not mentioned in most compendia, leading to frequent insurance denials.40 This creates a strong financial disincentive for manufacturers to pursue formal approval or even compendia listings for certain indications.

Pricing Pressures

Repurposed drugs face significant pricing pressures, particularly when they are off-patent and compete with cheaper generics for their original indications.63 Justifying a higher price for a repurposed drug requires a compelling case for its added clinical value, often necessitating new formulations or delivery methods that offer tangible benefits to patients.15 Payers are often reluctant to reimburse a more expensive variant of an already marketed product without clear evidence of superior outcomes.39

Global Variations

The complexity is further compounded by significant variations in reimbursement policies and processes across different countries and healthcare systems.54 This fragmented landscape makes it challenging for pharmaceutical companies to navigate market access globally, leading to delays and uncertainty in the reimbursement process and ultimately affecting patient access.54

7. Conclusions and Strategic Outlook

The landscape of pharmaceutical innovation is undergoing a profound transformation, with drug repurposing emerging as a strategic imperative for market leadership. This report has illuminated the multifaceted potential of leveraging existing drugs for new indications, driven by compelling economic advantages, advanced scientific methodologies, and evolving regulatory frameworks.

The core argument for drug repurposing is its superior risk-reward profile compared to traditional de novo drug discovery. With significantly reduced development costs (approximately $300 million versus $2-3 billion), accelerated timelines (3-12 years versus 10-17 years), and remarkably higher approval rates (around 30% versus less than 10%), repurposed drugs offer a more predictable and capital-efficient pathway to market. This economic reality enables pharmaceutical companies to profitably address unmet medical needs, particularly for rare and neglected diseases that were previously deemed financially unviable, thereby diversifying portfolios and fostering a more resilient business model.

Scientifically, the field is moving beyond serendipitous discoveries towards systematic, data-driven approaches. A deep understanding of drug pleiotropy, polypharmacology, and shared disease mechanisms, coupled with the transformative power of AI and bioinformatics, is revolutionizing candidate identification. Companies that invest in superior AI capabilities and effective access to integrated, high-quality data will gain a significant competitive advantage in identifying and validating promising candidates faster and more efficiently.

However, achieving market domination through repurposing is not without its challenges. The strict prohibition on manufacturer promotion of off-label uses necessitates careful compliance and robust internal policies to avoid severe legal penalties. The ethical imperative of transparent informed consent for patients, particularly for off-label uses, remains a critical area for responsible practice. Furthermore, reimbursement policies, which often view off-label uses as “experimental,” pose a significant barrier to market access, even for scientifically validated repurposed drugs. This necessitates proactive engagement with payers and strategic clinical trial design to generate evidence of value for new indications.

Actionable Recommendations for Market Domination:

- Prioritize Data-Driven Candidate Identification: Invest heavily in AI, machine learning, and bioinformatics platforms capable of integrating diverse datasets (genomics, proteomics, real-world evidence, patent literature). Develop internal expertise in these advanced analytical techniques to systematically identify and prioritize repurposing candidates with the highest probability of success.

- Proactive Intellectual Property Strategy: Develop a comprehensive IP strategy that focuses on securing method-of-use patents, novel formulation patents, and combination patents for repurposed drugs. Proactively seek Orphan Drug Designations for rare disease indications to leverage market exclusivity incentives. Conduct thorough patent searches to navigate prior art and avoid “evergreening” pitfalls.

- Strategic Regulatory Engagement: Engage early and proactively with regulatory bodies (FDA, EMA) to leverage expedited pathways like 505(b)(2) and Orphan Drug Designation. Design clinical trials specifically to meet the evidence requirements for new indications, ensuring that data generated supports both regulatory approval and reimbursement needs.

- Nuanced Pricing and Reimbursement Models: Develop value-based pricing models that clearly articulate the clinical and economic benefits of repurposed drugs for their new indications, especially when seeking a premium over existing generics. Engage early with payers and health technology assessment bodies to understand their evidence requirements and secure favorable reimbursement terms. Consider new formulations or delivery methods that offer tangible patient benefits to justify higher pricing.

- Robust Competitive Intelligence: Implement sophisticated competitive intelligence systems that integrate patent data, scientific literature, clinical trial registries, and real-world evidence. Utilize AI and NLP to gain a comprehensive, real-time understanding of competitor pipelines, regulatory shifts, and market opportunities, enabling agile strategic adjustments.

- Targeted Medical Education and KOL Engagement: Formal approval is the beginning, not the end. Invest in robust medical education campaigns and strategic Key Opinion Leader (KOL) engagement to inform healthcare professionals about new on-label indications, their supporting evidence, and optimal use. Leverage KOL networks to drive adoption and overcome any lingering perceptions of “off-label” or “experimental” use.

- Commitment to Ethical Practices: Uphold the highest ethical standards, particularly regarding patient safety and informed consent. Ensure transparent communication with patients about the approved status, risks, and benefits of any prescribed medication, whether on-label or off-label. Strictly adhere to regulations prohibiting off-label promotion.

- Foster Collaborative Ecosystems: Actively seek partnerships with academic institutions, non-profit organizations, and Contract Research Organizations (CROs). These collaborations can pool resources, share expertise, and de-risk early-stage repurposing efforts, particularly for indications with limited commercial appeal.

The future of pharmaceutical innovation will increasingly be defined by the ability to unlock the hidden potential within existing drug arsenals. By strategically embracing drug repurposing, pharmaceutical companies can not only achieve significant market advantages but also accelerate the delivery of much-needed therapies to patients worldwide, shaping a more efficient, responsive, and impactful healthcare landscape.

Works cited

- Off-label Use of Drugs | American Cancer Society, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/managing-cancer/treatment-types/off-label-drug-use.html

- Off-label use of drugs: An evil or a necessity? – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4743297/

- Off-label Use – Clinical Research Explained | VIARES, accessed July 27, 2025, https://viares.com/blog/clinical-research-explained/off-label-use/

- Off-label use | European Medicines Agency (EMA), accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary-terms/label-use

- Ten Common Questions (and Their Answers) About Off-label Drug Use – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3538391/

- Off-Label Pharmaceutical Marketing: How to Recognize and Report It – CMS, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.cms.gov/medicare-medicaid-coordination/fraud-prevention/medicaid-integrity-education/downloads/off-label-marketing-factsheet.pdf

- Off-Label Use vs Off-Label Marketing of Drugs: Part 1: Off-Label Use …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9998554/

- Off-Label Drugs: What You Need to Know | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.ahrq.gov/patients-consumers/patient-involvement/off-label-drug-usage.html

- Prescribing “Off-Label”: What Should a Physician Disclose? – AMA Journal of Ethics, accessed July 27, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/prescribing-label-what-should-physician-disclose/2016-06

- Drug repurposing: a systematic review on root causes, barriers and facilitators – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9336118/

- Drug Repurposing – CDCN – Castleman Disease Collaborative Network, accessed July 27, 2025, https://cdcn.org/repurpose/

- Drug repurposing: Clinical practices and regulatory pathways – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12048090/

- Drug Repurposing: The Discovery of New Uses for Existing Pharmaceutical Drugs, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.byarcadia.org/post/drug-repurposing-the-discovery-of-new-uses-for-existing-pharmaceutical-drugs

- Drug Repurposing and Polypharmacology: A Synergistic Approach in Multi-target based Drug Discovery | Frontiers Research Topic, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/34417/drug-repurposing-and-polypharmacology-a-synergistic-approach-in-multi-target-based-drug-discovery/magazine

- Reviving Dormant Assets: A Strategic Blueprint for Drug …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/reviving-a-discontinued-drug/

- Pharmacists: Unlocking Market Domination Through Strategic Drug Repurposing, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/pharmacists-can-play-key-role-in-drug-repurposing/

- Drug Repurposing: An Overview – DrugPatentWatch – Transform …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/drug-repurposing-an-overview/

- Drug Repurposing Strategy (DRS): Emerging Approach to Identify Potential Therapeutics for Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Infection – Frontiers, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/molecular-biosciences/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2021.628144/full

- Biopharmaceuticals: The Patent Implications of Drug Repurposing – PatentPC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-implications-of-drug-repurposing

- Intellectual Property Rights and Regulatory Considerations for Drug …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/intellectual-property-rights-and-regulatory-considerations-for-drug-repurposing/

- Off-label use of medicine: Perspective of physicians, patients, pharmaceutical companies and regulatory authorities – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4008928/

- Drug repurposing from the perspective of pharmaceutical companies – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5758385/

- Giving old drugs new life…to save lives – Wyss Institute, accessed July 27, 2025, https://wyss.harvard.edu/news/giving-old-drugs-new-life-to-save-lives/

- How drug repurposing can advance drug discovery: challenges and opportunities – Frontiers, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/drug-discovery/articles/10.3389/fddsv.2024.1460100/full

- Sildenafil – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sildenafil

- 10 Surprising Off-Label Uses for Prescription Medications – Pharmacy Times, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/10-surprising-off-label-uses-for-prescription-medications

- Repurposed Drugs | Emory University | Atlanta GA, accessed July 27, 2025, https://ott.emory.edu/industry/featured/repurposed.html

- Drug Repurposing Strategies, Challenges and Successes | Technology Networks, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.technologynetworks.com/drug-discovery/articles/drug-repurposing-strategies-challenges-and-successes-384263

- Examples of treatments used off-label – European Brain Council, accessed July 27, 2025, http://www.braincouncil.eu/golup/examples-of-off-label-use/

- The Rise, Fall and Subsequent Triumph of Thalidomide: Lessons Learned in Drug Development – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3573415/

- Off- label indications of aspirin in gynaecology and obstetrics outpatients at two Chinese tertiary care hospitals – BMJ Open, accessed July 27, 2025, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/12/2/e050702.full.pdf

- Off-label indications of aspirin in gynaecology and obstetrics outpatients at two Chinese tertiary care hospitals: a retrospective cross-sectional study, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8860038/

- Does Therapeutic Repurposing in Cancer Meet the Expectations of Having Drugs at a Lower Price?, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10097740/

- The Scientist’s Guide to Understanding FDA Drug Approval – Excedr, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.excedr.com/blog/fda-drug-approval-process-guide

- What Does it Take to Get a Medication Approved Through the FDA?, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/family-resources-education/700childrens/2018/03/what-does-it-take-to-get-a-drug-approved-through-the-fda

- Authorisation of medicines – EMA – European Union, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/what-we-do/authorisation-medicines

- Drug Repositioning – Benefits and Challenges for Lifecycle Management – Aptar, accessed July 27, 2025, https://aptar.com/resources/drug-repositioning-benefits-and-challenges-for-lifecycle-management/

- Advantages of Drug Repurposing – pharm-int – Pharmaceutics International, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.pharm-int.com/resources/advantages-of-drug-repurposing/

- The risk-reward balance in drug repurposing – Alacrita, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.alacrita.com/blog/the-risk-reward-balance-in-drug-repurposing

- REIMBURSEMENT FOR OFF LABEL DRUGS – MPN Research …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://mpnresearchfoundation.org/off-label-use-reimbursement/

- Off-Label Promotion – Medmarc, accessed July 27, 2025, https://medmarc.com/life-sciences-news-and-resources/publications/off-label-promotion

- GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Patent Strategy: Securing Patent Protection for New Use of Old Drugs | Foley & Lardner LLP, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.foley.com/insights/publications/2025/03/glp-1-receptor-agonists-patent-strategy-securing-patent-protection/

- A network approach to unravel pleiotropy and identify genetically… – ResearchGate, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/A-network-approach-to-unravel-pleiotropy-and-identify-genetically-informed-drug-targets_fig2_384824517

- Bayesian inference of genetic pleiotropy identifies drug targets and repurposable medicines for human complex diseases | medRxiv, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.03.17.25324106v2.full-text

- Polypharmacology: drug discovery for the future – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3809828/

- A Comparison of Network-Based Methods for Drug Repurposing along with an Application to Human Complex Diseases – MDPI, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/7/3703

- Disease networks and their contribution to disease understanding and drug repurposing. A survey of the state of the art | bioRxiv, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/415257v1.full-text

- Drug repurposing: approaches, methods and considerations | Elsevier, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.elsevier.com/industry/drug-repurposing

- Drug Repurposing: An Effective Tool in Modern Drug Discovery – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9945820/

- Drug Repurposing Market: Strategic Approaches, Technological, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/drug-repurposing-market/273130/

- Drug Repurposing Market Size to Hit USD 59.30 Billion by 2034 – Precedence Research, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.precedenceresearch.com/drug-repurposing-market

- (PDF) HARNESSING NATURAL LANGUAGE PROCESSING FOR AUTOMATED LITERATURE AND COMPETITIVE INTELLIGENCE IN DRUG DISCOVERY – ResearchGate, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392732009_HARNESSING_NATURAL_LANGUAGE_PROCESSING_FOR_AUTOMATED_LITERATURE_AND_COMPETITIVE_INTELLIGENCE_IN_DRUG_DISCOVERY

- The use of real-world data in drug repurposing – PMC, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8492393/

- Navigating Reimbursement Challenges – Number Analytics, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/navigating-reimbursement-challenges

- What is Competitive Intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry? – Lifescience Dynamics, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.lifesciencedynamics.com/press/articles/what-is-competitive-intelligence-in-the-pharma-industry/

- DrugPatentWatch 2025 Company Profile: Valuation, Funding & Investors | PitchBook, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/519079-87

- Cortellis Drug Discovery Intelligence Platform | Clarivate, accessed July 27, 2025, https://clarivate.com/life-sciences-healthcare/research-development/discovery-development/cortellis-pre-clinical-intelligence/

- DrugPatentWatch Pricing, Features, and Reviews (Jul 2025) – Software Suggest, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.softwaresuggest.com/drugpatentwatch

- DrugPatentWatch Review – Crozdesk, accessed July 27, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch/review

- Cortellis Pharma Competitive Intelligence & Analytics | Clarivate, accessed July 27, 2025, https://clarivate.com/life-sciences-healthcare/portfolio-strategy/competitive-intelligence/cortellis-competitive-intelligence-analytics/

- What are the top Biopharmaceutical Business Intelligence Services? – DrugPatentWatch, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-are-the-top-biopharmaceutical-business-intelligence-services/

- The Role of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Drug Approval – brilitas pharmaceuticals, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.brilitas.com/km/blog/medicines-2/the-role-of-the-european-medicines-agency-ema-in-drug-approval-with-brilitas-eu-33

- Drug Repurposing Market Size, Industry Trends And Future Outlook By 2033, accessed July 27, 2025, https://straitsresearch.com/report/drug-repurposing-market

- Comparing Pathways for Making Repurposed Drugs Available In The EU, UK, And US, accessed July 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11788669/

- What is the biggest hurdle in drug repurposing today?—with Mika Newton – YouTube, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrugP7WlJgI

- List of off-label promotion pharmaceutical settlements – Wikipedia, accessed July 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_off-label_promotion_pharmaceutical_settlements

- Defending Products Liability Suits Involving Off-Label Use: Does the Learned Intermediary Doctrine Apply? – Semmes, accessed July 27, 2025, https://semmes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/off-label-use.pdf

- Off-Label Use of Prescription Drugs – Congress.gov, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45792

- The Ethics of Off-Label Prescribing – Number Analytics, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ethics-off-label-prescribing

- Informed Consent for Off-Label Use of Prescription Medications …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/informed-consent-label-use-prescription-medications/2012-07

- Off-Label Drugs: Reimbursement Policies Constrain Physicians in Their Choice of Cancer Therapies – GAO, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/products/pemd-91-14

- Drug repurposing and the prior art patents of competitors Christian Sternitzke, accessed July 27, 2025, https://sternitzke.com/pre-publication/Drug_repurposing.pdf

- Full article: Drug repurposing in pharmaceutical industry and its impact on market access, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3402/jmahp.v2.22814

- From Literature to Knowledge Graphs to Drug Repurposing, accessed July 27, 2025, https://drugrepocentral.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.58647/REXPO.25000078.v1

- HCP and KOL Mapping: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharma Teams …, accessed July 27, 2025, https://intuitionlabs.ai/articles/hcp-kol-mapping-comprehensive-guide-pharma-teams

- KOL Mapping: How to Identify KOLs in Key Therapeutic Areas – Livestorm, accessed July 27, 2025, https://livestorm.co/blog/kol-mapping

- EMA: Drug repurposing efforts saw limited success during pilot – RAPS, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2025/7/ema-drug-repurposing-efforts-saw-limited-success-d

- The impact of drug pricing and reimbursement on the pharmaceutical industry, accessed July 27, 2025, https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/sponsored/the-impact-of-drug-pricing-and-reimbursement-on-the-pharmaceutical-industry/