Section 1: Executive Summary

Core Opportunity

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the strategic and financial viability of developing a novel Fixed-Dose Combination (FDC) analgesic. The core opportunity involves combining two well-established, off-patent generic pain medications into a single, proprietary oral dosage form. By leveraging the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, this strategy aims to transform commodity active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) into a differentiated, branded therapeutic asset. This approach is designed to address specific clinical needs in pain management while creating a new period of market exclusivity, thereby capturing significant value from a highly mature and commoditized segment of the pharmaceutical market.

Strategic Rationale

The value proposition for this venture is twofold, resting on a foundation of both clinical enhancement and commercial innovation:

- Clinical Value: The primary clinical rationale is the principle of multimodal analgesia, which posits that combining drugs with different mechanisms of action can provide superior pain relief, often with an improved safety profile.1 The FDC offers the potential for synergistic efficacy, allowing for lower doses of each component, which can reduce dose-dependent adverse events and improve patient tolerability. Furthermore, by simplifying the treatment regimen from multiple pills to a single tablet, the FDC is expected to significantly improve patient adherence, a key driver of positive therapeutic outcomes.3

- Commercial Value: The commercial strategy is a sophisticated life-cycle management play. An FDC of existing drugs is regulated as a new drug product, eligible for its own period of market exclusivity and patent protection. Approval via the 505(b)(2) pathway can confer three years of regulatory exclusivity, while a novel and non-obvious formulation can secure new patents. Historical data indicates that such FDCs add a median of 7.7 to 11.5 years of combined patent and market exclusivity beyond that of the individual generic components, effectively creating a high-margin branded product from low-cost inputs.5

Total Estimated Investment

The total capital investment required to bring this FDC product from concept to market is substantial and subject to the specific requirements of the clinical development program. The primary cost driver is the clinical trial(s) needed to satisfy the FDA’s “Combination Rule” (21 CFR 300.50), which mandates that the contribution of each active ingredient to the product’s overall effect be demonstrated. The total estimated investment is projected to be in the range of $15 million to $75 million. A more precise budget can only be established following the pivotal pre-Investigational New Drug (pre-IND) meeting with the FDA, which will define the scope of the required clinical studies.

Projected ROI and Financials

Financial modeling, based on a set of conservative assumptions regarding market penetration, pricing, and reimbursement, indicates a strong potential for return on investment. Over a 10-year post-launch forecast period, the project is projected to achieve a positive Net Present Value (NPV) and a compelling Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Peak annual sales are forecast to be significant, contingent upon successful execution of the market access strategy. The financial outcomes are highly sensitive to three key variables: the final negotiated price with payers, the total cost of the clinical development program, and the duration of market exclusivity achieved through intellectual property protection.

Key Risks and Mitigation

The venture carries significant but manageable risks inherent to pharmaceutical development:

- Regulatory Risk: The scope, complexity, and cost of the clinical trials required by the FDA represent the largest uncertainty. This risk is mitigated by engaging expert 505(b)(2) consultants to design a robust and efficient clinical plan and by treating the pre-IND meeting as a critical go/no-go decision gate.

- Market Access Risk: Payers may exhibit resistance to granting premium pricing for an FDC composed of inexpensive generic drugs. This risk is addressed by designing the clinical program to generate compelling pharmacoeconomic data that demonstrates clear value beyond mere convenience, such as superior efficacy or a meaningful reduction in adverse events.

- Intellectual Property Risk: Securing strong, defensible patents for a combination of known substances is challenging due to the legal standard of non-obviousness. This risk is mitigated by focusing formulation and clinical development on generating data that demonstrates unexpected or synergistic results, which form the strongest basis for patentability.

Definitive Recommendation

The development of a generic FDC analgesic represents a high-risk, high-reward opportunity. The analysis concludes that this is a strategically sound and financially attractive venture, provided that key milestones can be met. It is recommended to proceed with an initial investment phase focused on candidate selection, pre-formulation studies, and preparation for a pre-IND meeting with the FDA. A final decision to commit to the full development program should be contingent upon receiving favorable feedback from the FDA that confirms a clinical trial pathway consistent with the financial projections outlined in this report.

Section 2: The Value Proposition of Combination Analgesia

The strategic foundation for developing a fixed-dose combination (FDC) analgesic rests on a dual value proposition that addresses unmet needs for patients and prescribers while creating a significant commercial opportunity. This section details the clinical imperative for multimodal pain management and the compelling commercial rationale for transforming generic assets into a proprietary, value-added therapeutic.

2.1 The Clinical Imperative: Multimodal Analgesia

Pain is not a monolithic sensation but a complex pathophysiological process involving multiple signaling pathways in both the peripheral and central nervous systems.2 Consequently, single-agent therapies, which typically target only one mechanism, often provide insufficient pain relief or require doses high enough to cause limiting side effects.7 The concept of multimodal analgesia, which involves the concurrent administration of two or more analgesic agents with different mechanisms of action, has become a cornerstone of modern pain management.2 This approach seeks to attack the pain process from multiple angles simultaneously, leading to superior clinical outcomes.

Synergistic Efficacy

The primary clinical objective of an analgesic FDC is to achieve an additive or, ideally, a synergistic therapeutic effect.1 Synergy occurs when the combined analgesic effect of two drugs is greater than the sum of their individual effects. This can be achieved by combining agents that act on different points in the pain pathway. For instance, combining a centrally acting agent like tramadol (which affects μ-opioid receptors and serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake) with a peripherally acting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) like diclofenac (which inhibits cyclo-oxygenase enzymes at the site of injury) can provide more comprehensive pain control than either agent alone.9 Clinical studies of existing FDCs, such as tramadol/paracetamol, have confirmed that the combination provides better efficacy than either component administered individually in acute pain models like third molar extraction.1

Improved Safety and Tolerability (Dose-Sparing Effect)

A critical consequence of synergistic efficacy is the ability to achieve robust pain relief using lower doses of each individual component.1 This dose-sparing effect is a fundamental advantage of FDCs, as it directly translates to an improved safety and tolerability profile. Many of the most significant adverse events associated with analgesics are dose-dependent. For example, high doses of opioids are associated with an increased risk of respiratory depression, sedation, nausea, and constipation, while high doses of NSAIDs increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal toxicity.9 By combining an opioid with an NSAID, it is possible to achieve a target level of analgesia with a significantly lower total opioid dose, thereby “sparing” the patient from the side effects of higher-dose opioid monotherapy.8 This opioid-sparing effect is not only a clinical benefit but also a significant public health advantage in the context of the ongoing opioid crisis.

Evidence from Existing Combinations

The clinical value of analgesic FDCs is not merely theoretical; it is well-established in clinical practice.

- Tramadol/Paracetamol: This combination leverages the central action of tramadol with the central and peripheral effects of paracetamol. Its synergistic action allows for effective management of moderate to severe pain with lower doses of each substance, improving its overall pharmacological profile.6

- Tramadol/Diclofenac: This FDC combines an atypical opioid with a potent NSAID and has demonstrated substantial efficacy and safety in treating acute severe pain, including postoperative pain and musculoskeletal pain. Evidence shows this combination provides multimodal analgesia at lower, better-tolerated doses than monotherapy with either drug.9

- Ibuprofen/Acetaminophen: An FDC of these two common over-the-counter analgesics has been shown to be highly effective for acute dental pain, providing pain relief superior to or similar to some opioid combinations but with fewer adverse events.10

2.2 The Commercial Rationale: Creating a Differentiated, Proprietary Asset

While the clinical rationale provides the medical justification for an FDC, the commercial rationale provides the business case. The strategy is to leverage established clinical benefits to create a new, proprietary product with a defensible market position and a high-margin revenue stream.

Patient Adherence and Convenience

The most immediate and tangible benefit of an FDC is the reduction in “pill burden.” For patients with conditions requiring multiple medications, simplifying the regimen to a single tablet can dramatically improve compliance and adherence.3 Non-adherence to therapy is a major global health problem that leads to poor clinical outcomes and increased healthcare system costs.4 A systematic review of 21 studies covering over 27,000 subjects showed consistently better compliance and therapeutic effect among patients receiving FDCs.3 This improved convenience is highly valued by both patients and physicians, making an FDC a preferred therapeutic option.3

Life-Cycle Management and Market Exclusivity

The core of the commercial opportunity lies in the regulatory and intellectual property advantages afforded to FDCs. An FDC of two previously approved drugs is considered a “new drug product” by the FDA, not a generic. As such, it is eligible for approval via the 505(b)(2) pathway, which can confer its own period of market exclusivity.13 If the approval requires new clinical investigations—which is almost certain for an FDC under the FDA’s Combination Rule—the product is granted

three years of market exclusivity.5 This exclusivity prevents the FDA from approving a generic version of the FDC for that period, providing an initial window of market protection.

Patent Extension

More significant than regulatory exclusivity is the potential for new patent protection. A combination of known drugs can be patented if the combination is shown to be novel, useful, and, most critically, non-obvious.5 Demonstrating an unexpected synergistic effect or a unique formulation that improves stability or bioavailability can overcome the “obviousness” hurdle.15 A successful patent strategy transforms the commercial landscape. Instead of a short three-year exclusivity, the FDC can gain long-term market protection. Historical analysis of FDCs approved between 1980 and 2012 found that those without a new molecular entity added a median of

9.7 years of patent and market exclusivity protection compared to their single-ingredient components.5 This is the central mechanism for value creation: converting two low-margin, off-patent generic drugs into a single, high-margin, patent-protected branded asset for a decade or more.

Cost Efficiencies

While secondary to the IP opportunity, FDCs also offer tangible cost savings across the healthcare value chain. For manufacturers, producing, packaging, and distributing one product is more efficient than two.5 For patients, a single prescription typically means a single co-payment instead of two, reducing their out-of-pocket costs.5 For physician offices and pharmacies, managing one prescription is administratively simpler than managing two separate ones.3

The success of this venture, however, cannot rely on the argument of convenience alone. Payers are increasingly sophisticated and often view FDCs with skepticism, particularly when the components are available as low-cost generics.17 They may perceive the FDC as a life-cycle extension strategy designed primarily to protect revenue rather than to deliver substantial clinical value. Therefore, to secure favorable reimbursement and justify a price premium, the commercial value story must be inextricably linked to the clinical value proposition. The development program must be designed not just to gain regulatory approval, but to generate robust data demonstrating that the FDC offers superior efficacy or, more compellingly, a significantly improved safety profile. Evidence of an opioid-sparing effect, for example, can be translated into a powerful pharmacoeconomic argument about reducing the costs associated with opioid-related adverse events and addiction. The narrative presented to payers must shift from “this is a more convenient pill” to “this is a safer, more effective therapy that provides better outcomes.”

Ultimately, the entire FDC strategy is an investment in creating intellectual property. The financial return is not driven by manufacturing efficiencies but by the high-margin sales enabled by a new, defensible period of market exclusivity. The difference between the negligible profit margins of the two generic components and the potential revenue from the branded FDC is a direct function of the duration and strength of the IP generated. Therefore, every strategic decision, from candidate selection to clinical trial design, must be viewed through the lens of its contribution to building a robust and defensible IP position.

Section 3: Candidate Selection and Development Strategy

The transition from a conceptual business strategy to a viable pharmaceutical product requires a rigorous, data-driven process for selecting the right drug candidates and defining a technically sound development and manufacturing plan. This section outlines a multi-factorial analysis for identifying an optimal analgesic combination and details the formulation and manufacturing pathway, emphasizing a capital-efficient partnership model.

3.1 Identifying a Winning Combination: A Multi-Factorial Analysis

The selection of the two generic active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is the most critical foundational decision in the FDC development program. An ideal combination must satisfy clinical, market, and technical criteria to maximize the probability of success.

- Clinical Synergy and Rationale: The foremost criterion is a strong scientific and medical rationale for the combination. The chosen drugs must have complementary, non-redundant mechanisms of action that create a plausible basis for additive or synergistic efficacy.1 Combining drugs that act on the same target or pathway is considered irrational and should be avoided.1 The goal is to select a pair where the combined effect on pain is mechanistically sound and can be convincingly demonstrated in a clinical trial.

- Market Opportunity and Prescribing Patterns: The most commercially viable FDC candidates are those that formalize an existing, informal clinical practice. Analyzing prescribing data to identify two analgesics that are frequently co-prescribed as separate pills (“loose-dose combination”) provides strong evidence of physician acceptance and a pre-existing market need.5 This de-risks the commercial adoption phase, as the FDC is not introducing a novel therapeutic concept but rather optimizing a familiar one. Common co-prescribed categories for pain include an opioid with an NSAID, an opioid with acetaminophen, or an NSAID with acetaminophen.18

- Formulation Feasibility: The APIs must be physically and chemically compatible to be combined into a single, stable dosage form. A thorough pre-formulation assessment is required to identify potential challenges such as chemical degradation when the APIs are in direct contact, hygroscopicity issues where one API absorbs moisture and destabilizes the other, or significant differences in particle size and density that could lead to problems with content uniformity during manufacturing.21 A large differential in the required dose of each API can also pose significant formulation and processing challenges.21

- Intellectual Property Landscape: A preliminary freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis is necessary to ensure that an FDC of the chosen candidates does not infringe on existing patents held by other companies. Concurrently, an initial patentability assessment should be conducted to evaluate the potential for securing new, defensible patents on the combination.

Proposed Candidate for Analysis

Based on the criteria above, this report will use a fixed-dose combination of Tramadol and Diclofenac as the model for detailed regulatory and financial analysis. This pairing is strategically sound for several reasons:

- Strong Clinical Rationale: It combines tramadol, an atypical centrally acting analgesic with a dual mode of action (μ-opioid receptor agonism and monoamine reuptake inhibition), with diclofenac, a potent peripherally acting NSAID.9 This provides a clear basis for multimodal analgesia.

- Validated Combination: The tramadol/diclofenac FDC is not a purely theoretical concept. It has been successfully developed and is used in clinical practice in markets outside the U.S. (e.g., India), with substantial scientific literature supporting its efficacy and safety for acute severe pain, including postoperative and musculoskeletal pain.9 This existing data strengthens the rationale presented to the FDA and reduces scientific risk.

- Clear Market Need: The combination of an opioid-like drug with an NSAID is a standard approach for managing moderate-to-severe acute pain, indicating a large and established market of potential users.9

3.2 Formulation and Manufacturing Pathway

Once the API candidates are selected, the focus shifts to developing a robust and scalable manufacturing process. For a new venture, the most prudent and capital-efficient approach is to partner with a specialized third-party organization.

Dosage Form Selection

The oral solid dosage (OSD) form, specifically a tablet, is the logical choice for this product. Tablets are the most widely accepted dosage form by patients and physicians due to their ease of administration, accurate dosing, and good stability.3 From a manufacturing perspective, tablet production is a mature, well-understood, and cost-effective process.22 This analysis will proceed on the assumption of developing a standard immediate-release bilayer tablet, which can help mitigate potential API incompatibility issues by keeping the two active layers physically separate until ingestion.

Key Formulation Challenges

The development of a successful FDC tablet formulation requires overcoming several technical hurdles:

- API-Excipient Compatibility: Both tramadol and diclofenac must be compatible not only with each other but also with the inactive ingredients (excipients) used to form the tablet, such as binders, fillers, and lubricants. Incompatibility can lead to degradation and the formation of impurities over the product’s shelf life.21

- Content Uniformity: The manufacturing process must guarantee that every tablet produced contains the exact specified dose of both APIs. Achieving this is a primary focus of process validation and is critical for patient safety and regulatory approval, especially when the doses of the two APIs are different.21

- Bioavailability and Bioequivalence: A critical regulatory requirement is to demonstrate that the FDC tablet delivers both drugs to the bloodstream in the same manner as taking the two individual tablets concurrently. The formulation must be carefully designed to ensure that the release and absorption profiles of both tramadol and diclofenac from the single FDC tablet are bioequivalent to the co-administered reference products. Failure to meet bioequivalence endpoints is a common and costly reason for the failure of FDC development programs.24

Manufacturing Strategy: The CDMO Partnership Model

Developing and manufacturing a novel FDC requires specialized expertise, advanced analytical capabilities, and GMP-certified facilities. For a company focused on this single asset, building this infrastructure internally would involve prohibitive capital expenditure and significant time delays. Therefore, the recommended strategy is to outsource these activities to a reputable Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization (CDMO) with proven experience in FDC products.12

A CDMO partnership offers several key advantages:

- Access to Expertise: CDMOs provide immediate access to teams of formulation scientists, analytical chemists, and process engineers with deep experience in solving the specific challenges of FDCs.12

- Capital Efficiency: It eliminates the need for investment in manufacturing plants and equipment, converting a large fixed cost into a variable, project-based expense.26

- Speed to Market: Leveraging an existing CDMO infrastructure and experience can significantly shorten development timelines compared to building capabilities from the ground up.12

- Regulatory Compliance: Established CDMOs operate under cGMP standards and have experience in preparing the Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) section of the NDA, which is a critical component of the regulatory submission.

While the regulatory strategy and clinical trials are often seen as the primary hurdles, the technical aspects of formulation and manufacturing should not be underestimated. A small, upfront investment in thorough pre-formulation studies, API compatibility testing, and feasibility assessments represents a critical de-risking activity. These early technical studies are essential not only to prevent a late-stage failure in a pivotal bioequivalence study but also to develop a credible and technically sound CMC plan. This plan is a prerequisite for a successful pre-IND meeting, as the FDA will expect a clear and well-supported strategy for producing a consistent, stable, and high-quality clinical trial material before allowing human studies to proceed.13

Section 4: Navigating the Regulatory Gauntlet: The 505(b)(2) Pathway

The regulatory strategy is the central pillar of the FDC development plan. The choice of the 505(b)(2) pathway is a deliberate decision designed to balance innovation with efficiency, providing a structured, lower-cost route to market compared to developing a new molecular entity (NME) from scratch. This section provides a detailed roadmap of this pathway, highlighting its advantages, the critical hurdles that must be overcome, and the projected timeline for approval.

4.1 An Overview of the 505(b)(2) Advantage

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, created three primary pathways for drug approval in the U.S. Understanding their distinctions is fundamental to appreciating the strategic value of the 505(b)(2) route.13

- The “Hybrid” Application: The 505(b)(2) pathway is a full New Drug Application (NDA) that allows a sponsor to rely, in part, on data not developed by them—specifically, the FDA’s previous findings of safety and effectiveness for a previously approved drug, known as a “listed drug” or “reference listed drug”.13 This “right of reference” means the sponsor does not need to conduct a full suite of preclinical toxicology studies or large-scale Phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials to re-establish the safety and efficacy of the individual components. Instead, the sponsor must provide “bridging” data that scientifically justifies the reliance on the existing information for their new, modified product.13

- Ideal for FDCs: This pathway is perfectly suited for developing FDCs of previously approved drugs like tramadol and diclofenac.14 The development program can focus exclusively on demonstrating the safety and efficacy of the

combination product, leveraging the vast body of existing knowledge on the individual agents. - Contrast with Other Pathways: The strategic positioning of the 505(b)(2) pathway becomes clear when compared to the other two routes.

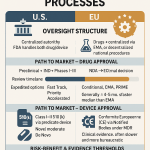

Table 1: Comparison of FDA Approval Pathways

| Feature | 505(b)(1) NDA (New Molecular Entity) | 505(b)(2) NDA (Hybrid/Value-Added) | 505(j) ANDA (Generic) |

| Description | A “stand-alone” application for a new active ingredient not previously approved by the FDA.28 | A full NDA that relies on existing data for a previously approved drug, plus new “bridging” studies for the modification.13 | An “abbreviated” application for a duplicate of an existing approved drug (the RLD).28 |

| Data Requirement | Full preclinical and clinical (Phase 1, 2, 3) program conducted by the sponsor.31 | Relies on FDA’s findings for RLD; requires new bridging studies (e.g., bioequivalence, clinical trial) to support the change.13 | Must demonstrate bioequivalence to the RLD and sameness in active ingredient, dosage form, strength, etc..28 |

| Typical Development Cost | >$1 billion, with some estimates reaching $2.6 billion.31 | $5 million – $200 million, highly dependent on the scope of required bridging studies.33 | Significantly lower, focused primarily on formulation and bioequivalence studies. |

| Typical Development Timeline | 10 – 15 years from discovery to approval.13 | 3 – 8 years from concept to approval.33 | 2 – 4 years. |

| Market Exclusivity | 5 years for a New Chemical Entity (NCE).33 | 3 years for requiring new clinical studies; potential for 5 or 7 years in specific cases (e.g., orphan drug).13 | 180 days for the first generic filer to challenge a patent (Paragraph IV).32 |

4.2 The Combination Rule (21 CFR 300.50): The Central Hurdle

While the 505(b)(2) pathway provides significant advantages, it is not a simple administrative process. For FDCs, approval is contingent upon satisfying a specific and demanding regulation known as the “Combination Rule”.29

- The Core Requirement: Codified in 21 CFR § 300.50, the rule states that two or more drugs may be combined in a single dosage form only when “each component makes a contribution to the claimed effects”.29 This means it is insufficient to merely show that the combination product is effective. The sponsor must provide rigorous evidence that both Drug A and Drug B are necessary to achieve the observed therapeutic benefit. The FDA’s intent is to prevent “irrational” combinations where one component adds no value but may add risk or cost.35

- The Factorial Clinical Trial: The standard and most direct method for satisfying the Combination Rule is to conduct a clinical trial with a factorial design.29 This type of study is specifically designed to isolate the effect of each component and the combination. For the proposed Tramadol/Diclofenac FDC, a typical factorial trial would need to enroll patients with a specific type of acute pain (e.g., post-surgical pain) and randomize them into at least four parallel treatment arms 29:

- Placebo: To establish the baseline effect.

- Tramadol alone: To measure the effect of the first component.

- Diclofenac alone: To measure the effect of the second component.

- Tramadol/Diclofenac FDC: To measure the effect of the combination.

The primary endpoint would be a measure of pain relief over a set period. The trial would be considered successful if it demonstrates that the FDC arm is statistically superior to both the Tramadol-alone arm and the Diclofenac-alone arm, thus proving that both components are contributing to the overall effect.

- Implications for Cost and Timeline: This factorial clinical trial is the single most significant undertaking in the entire development program. It is the primary driver of both cost and time. Analysis of previously approved 505(b)(2) FDCs shows that two-thirds required at least one Phase 2 or 3 study for approval, with a substantial number requiring more than four such studies.29 This underscores a critical point: the 505(b)(2) pathway for an FDC is a clinical development program, not merely a reformulation exercise. The investment required is measured in tens of millions of dollars, and the timeline is measured in years.

4.3 Projected Timeline and FDA Engagement

The regulatory process is a structured sequence of events, with one particular milestone holding disproportionate importance for the project’s viability.

- Step 1: Pre-IND Meeting: This is the most critical meeting in the entire development process.13 Before committing the capital to a large clinical trial, the sponsor prepares a comprehensive briefing package outlining the product, the clinical rationale, the CMC plan, and the proposed design of the factorial clinical trial. The objective of the meeting is to present this plan to the relevant FDA review division and gain their feedback and, ideally, their concurrence on the proposed development program.13 A positive outcome from this meeting provides a clear and de-risked path forward. An unfavorable outcome, such as the FDA requiring multiple pivotal trials or a much larger or more complex study design, could increase costs to a point where the project is no longer financially viable. This meeting, therefore, serves as the project’s primary strategic inflection point and a key go/no-go decision gate for investors.

- Step 2: IND Submission: Following a successful pre-IND meeting and incorporation of the FDA’s feedback, the sponsor finalizes the clinical trial protocol and submits the formal Investigational New Drug (IND) application. Once the IND is active (typically 30 days after submission unless the FDA places a clinical hold), the sponsor can begin enrolling patients in the clinical trial.

- Step 3: Clinical “Bridging” Studies: This phase involves the execution of the factorial trial(s) as agreed upon with the FDA. This is the longest phase of the project, typically taking 18-24 months to complete enrollment, treatment, and data analysis.

- Step 4: NDA Submission and Review: Once the clinical trial is complete, all CMC, nonclinical (if any), and clinical data are compiled into the 505(b)(2) NDA and submitted to the FDA. The FDA then conducts its formal review. It is a common misconception that 505(b)(2) applications have a faster review time. The statutory review clock under the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) is the same for 505(b)(2) and 505(b)(1) applications, typically 10 months for a standard review.37 The time and cost savings of the 505(b)(2) pathway are realized in the reduced scope of the

development program, not in an abbreviated agency review period.13 - Total Estimated Timeline: From project inception to potential FDA approval, the estimated timeline is 3 to 5 years.

The strategic decision to use the 505(b)(2) pathway must be made with a clear understanding of its nature. It is a powerful tool for cost reduction relative to the billion-dollar cost of NME development, but it is not a shortcut that bypasses the FDA’s rigorous standards for safety and efficacy.31 The program requires a substantial clinical investment to generate the new data necessary to bridge to the existing knowledge base. Success hinges on a meticulously planned strategy, deep regulatory expertise, and, most importantly, achieving alignment with the FDA on the scope of that clinical investment at the pre-IND meeting.

Section 5: Comprehensive Financial Analysis and Investment Profile

A thorough financial analysis is essential to quantify the investment required for the FDC project, understand its cost structure, and ultimately determine its potential for profitability. This section provides a detailed breakdown of the projected costs, from initial development through manufacturing and intellectual property protection. The financial profile of this venture is characterized by a significant upfront investment in research and development, followed by low marginal production costs post-approval, a model typical of branded pharmaceutical products.

5.1 Deconstructing Development and Approval Costs

The total cost to achieve FDA approval is the sum of several distinct, multi-million-dollar components. The clinical program represents the largest and most variable expense.

Table 2: Estimated Cost Breakdown for 505(b)(2) FDC Development Program

| Cost Category | Low Estimate | High Estimate | Key Assumptions & Drivers |

| Clinical Program | $10,000,000 | $50,000,000 | The primary driver is the size, duration, and complexity of the factorial trial(s) required by the FDA’s Combination Rule.29 Costs include CRO fees, patient recruitment for an acute pain model, clinical site management, and data analysis. The high end of the range reflects the potential need for more than one pivotal study. |

| CMC & Formulation Development | $2,000,000 | $5,000,000 | Includes costs for partnering with a CDMO for formulation development, analytical method development and validation, manufacturing of GMP-grade clinical trial materials, and conducting multi-year stability studies.22 |

| Regulatory & Consulting | $1,000,000 | $2,000,000 | Fees for specialized 505(b)(2) regulatory consultants to guide strategy, prepare briefing documents, manage FDA interactions (especially the pre-IND meeting), and compile the final NDA submission.14 |

| FDA User Fees (PDUFA) | $4,000,000 | $4,100,000 | The Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) fee for an NDA with clinical data. This is a fixed fee set annually by the FDA. The FY2024 fee is approximately $4.04 million. |

| Total Estimated Development Cost | $17,000,000 | $61,100,000 | This range represents the total projected cash outlay to reach the point of potential FDA approval. |

5.2 Manufacturing and Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

In stark contrast to the high development costs, the ongoing manufacturing cost per unit for the FDC product is expected to be very low. This creates the high gross margin potential that is central to the project’s ROI.

- API Sourcing: The two primary inputs are the generic APIs for tramadol and diclofenac. The cost of API is generally the most significant component of a generic drug’s production cost, often accounting for approximately 52% of the total cost of goods.39 However, for established generics like these, API prices are relatively low due to a competitive global supply market. Based on publicly available data on API exports from major manufacturing hubs like India, the average price for many common APIs ranges from $10 to $1,000 per kilogram.40 For the purpose of this model, a blended cost for the required amount of tramadol and diclofenac per tablet is estimated to be in the range of $0.04 to $0.14.

- Conversion Cost: This represents the cost of all other manufacturing steps: combining the APIs with excipients, granulating, pressing the material into tablets, coating, and packaging. Extensive analysis of generic solid oral dosage form manufacturing has established a well-accepted industry benchmark for this conversion cost at approximately $0.01 per tablet.40 This figure includes operating costs, depreciated capital costs, and compliance with current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) standards.

- Total Estimated COGS: The total COGS per tablet is the sum of the API costs and the conversion cost. Based on these inputs, the fully loaded COGS for the final FDC product is projected to be in the range of $0.05 to $0.15 per tablet. This extremely low marginal cost of production highlights that the project’s profitability is not dependent on manufacturing efficiency but rather on the ability to secure a premium price and sufficient sales volume in the market.

5.3 Licensing and Intellectual Property Costs

Protecting the innovation created through the FDC development program is paramount to securing the long-term revenue stream. This requires a proactive and strategic investment in intellectual property.

- Patent Prosecution: This includes the legal fees associated with drafting, filing, and prosecuting new patent applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and potentially in other key international markets. The patents will seek to protect the novel aspects of the FDC, such as the specific formulation, the unique dosage ratio, or a method of use for a specific indication based on data from the clinical trial.15 The estimated cost for a robust patent prosecution strategy is

$100,000 to $300,000. - Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Before significant investment is made, a comprehensive FTO analysis must be conducted by patent attorneys to ensure that the proposed FDC product does not infringe on any valid, existing patents. This is a critical de-risking step to avoid costly future litigation. The cost of this analysis is typically included within the broader legal and IP budget.

- In-Licensing (if applicable): This analysis assumes that the FDC will be developed using standard formulation technologies that are in the public domain. If, however, a proprietary drug delivery system or a novel formulation technology from a third party is required to achieve the desired product profile (e.g., to ensure stability or achieve bioequivalence), the costs would include licensing fees and potential future royalties to that third party. Such a scenario would need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

The financial structure of this venture is clear: it requires a substantial, high-risk, fixed investment in R&D and IP creation, which, if successful, unlocks the ability to produce a product with very low variable costs. The entire business case rests on the ability of future high-margin sales to recoup this initial investment and generate a significant profit over the product’s protected life. This is the classic economic model of the branded pharmaceutical industry, and all strategic planning must be aligned with its realities.

Section 6: Market Landscape and Commercialization Strategy

Successful commercialization of the Tramadol/Diclofenac FDC hinges on a nuanced understanding of the market environment and a sophisticated strategy for pricing, reimbursement, and market access. The primary challenge is not a lack of clinical need but the deeply entrenched use of low-cost generic alternatives. The commercial plan must be architected to overcome this market inertia by demonstrating superior value that justifies a premium price and a change in prescribing behavior.

6.1 Market Sizing and Competitive Environment

- Overall Pain Market: The U.S. pain management drug market is a vast and mature sector, valued at over $31 billion in 2023 and projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 4.1% through 2033.41 The oral route of administration is the dominant segment, reflecting its convenience and patient acceptance.43 This large, stable market provides a substantial revenue opportunity for a new entrant that can capture even a modest share.

- Target Segment: The FDC is specifically designed to target the treatment of moderate-to-severe acute pain. This includes prevalent conditions such as post-surgical pain, acute musculoskeletal injuries (e.g., sprains, fractures), and flares of chronic conditions like osteoarthritis.9 The addressable patient population consists of individuals for whom a physician would typically consider prescribing a combination of an opioid or opioid-like drug and an NSAID.

- Competitive Landscape: The most formidable competitor is not another branded FDC, but the widespread and long-standing clinical practice of prescribing generic tramadol and generic diclofenac as two separate prescriptions—a “loose-dose combination”.8 This approach is familiar to physicians, clinically effective, and, most importantly, extremely inexpensive. The entire commercial and clinical strategy must be designed to answer one critical question for both prescribers and payers: “Why should we use your more expensive, single-pill FDC when we can achieve a similar outcome with two cheap generics?” The success of the product depends entirely on providing a compelling, evidence-based answer to this question.

6.2 Pricing and Reimbursement Strategy: Overcoming the Payer Hurdle

Securing favorable reimbursement from payers (insurance companies, pharmacy benefit managers, and government programs) is the most critical commercial challenge. Payers are highly cost-conscious and view FDCs of generic components with inherent skepticism.

- The “1+1 = 1.6” Reality: Payers do not typically price an FDC at the simple sum of its components’ branded prices. Instead, they benchmark against the cost of the readily available generic alternatives. An analysis of payer behavior for FDCs where the individual components are available shows that the price achieved by the FDC is, on average, equivalent to only 1.6 times the price of one monotherapy, representing a significant discount from a simple “1+1=2” pricing model.17 This dynamic must be factored into all revenue projections. When one component is already heavily genericized, the FDC price often collapses to be only slightly more than the price of the single branded component in the mix.17

- Value-Based Argument: To command a price that ensures profitability, the reimbursement strategy must be built on a robust value proposition supported by hard data from the clinical development program. The argument must pivot away from convenience and focus on demonstrable clinical and economic value.45 The key pillars of this value argument are:

- Superior Clinical Outcomes: Data from the factorial clinical trial must clearly demonstrate that the FDC provides statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in pain relief compared to each monotherapy.

- Enhanced Safety Profile: This is potentially the most powerful argument. Data showing a significant opioid-sparing effect or a reduction in NSAID-related gastrointestinal adverse events can be used to argue that the FDC is a safer therapeutic option.

- Pharmacoeconomic Benefits: A health economics model should be developed to translate these clinical benefits into cost savings for the healthcare system. For example, better pain control could lead to shorter hospital stays or fewer emergency room visits. An improved safety profile could reduce the costs associated with managing adverse events. This evidence is crucial for convincing payers that the FDC’s higher upfront cost is justified by downstream savings.46

- Pricing Benchmarks: The pricing strategy must be informed by the actual acquisition cost of the generic competitors. The National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) is a benchmark published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that reflects the average price paid by retail pharmacies to acquire drugs.48 By analyzing the NADAC for generic tramadol and generic diclofenac, a precise cost for the “loose-dose” competitor can be established. The FDC’s Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) will then be set at a premium to this generic benchmark, with the size of the premium justified by the value-based arguments above.49

6.3 Market Access and Go-to-Market Plan

Beyond pricing, achieving market access involves navigating a series of technical and administrative hurdles that can prevent a product’s uptake even if it is favorably priced.

- The 505(b)(2) Market Access Challenge: A critical issue with 505(b)(2) products is that they are generally not considered therapeutically equivalent to their reference listed drugs and are therefore not automatically substitutable at the pharmacy level.28 This means the FDC must be prescribed by name and actively adopted by physicians and placed on payer formularies.

- Securing a Unique Reimbursement Code: A crucial operational step is to secure a unique National Drug Code (NDC) and, for products used in institutional settings, a unique Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) J-code. These codes are essential for accurate billing and reimbursement.50 When a 505(b)(2) product shares a generic name with other products but has a different price and reimbursement status, it can create significant confusion in hospital and pharmacy electronic health record (EHR) and billing systems.28 If a provider dispenses the FDC but accidentally bills using the generic code, the claim will be denied, resulting in a financial loss for the provider. This risk of reimbursement errors can be a major deterrent to product adoption. Proactively working with CMS and other coding bodies to secure a unique code is a critical pre-launch activity.50

- Targeted Promotion and Education: The go-to-market plan will not involve a large primary care sales force. Instead, it will be a targeted promotional effort focused on key prescribers in the acute pain space, such as orthopedic surgeons, general surgeons, and emergency department physicians. The core of the marketing message will be the clinical data package from the development program, emphasizing the evidence for superior efficacy and safety. A dedicated market access team will engage directly with key national and regional payers to present the clinical and pharmacoeconomic value dossier and negotiate formulary placement.

The commercial success of this FDC is not guaranteed by FDA approval. It must be earned by winning a two-front battle: first, by convincing clinicians that the product’s benefits are significant enough to change their prescribing habits, and second, by convincing payers that this added value justifies its premium cost. This requires a strategy built on robust evidence and a proactive approach to navigating the complex administrative landscape of the U.S. healthcare system.

Section 7: Strategic Synthesis and Return on Investment (ROI) Projection

This final section integrates the clinical, regulatory, manufacturing, and commercial analyses into a cohesive financial forecast and provides a definitive strategic recommendation. The financial model synthesizes the key assumptions and variables discussed throughout this report to project the potential return on investment, while a sensitivity analysis highlights the key drivers of risk and value.

7.1 Integrated Financial Model (10-Year Pro-Forma)

The financial viability of the Tramadol/Diclofenac FDC project is assessed using a 10-year pro-forma financial model, commencing from the product’s launch. The model is built upon a series of conservative, evidence-based assumptions.

- Revenue Projections: Revenue is projected based on the size of the addressable acute pain market. The model assumes a gradual market penetration, following a standard S-curve adoption model that reaches a peak market share in year 6-7 post-launch. The net price per unit is based on the pricing strategy outlined in Section 6, assuming a premium over the NADAC of the combined generics, but also factoring in a realistic discount negotiated with payers, consistent with the “1+1 = 1.6” benchmark.17

- Cost Projections:

- Upfront R&D: The total estimated development cost from Section 5 (mid-range estimate of ~$39 million) is treated as a sunk cost for the purpose of the post-launch P&L but is fully accounted for in the NPV and IRR calculations.

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): Calculated as a variable cost based on the projected sales volume and the per-unit COGS estimate of $0.10 per tablet, as derived in Section 5.2.

- Sales, General & Administrative (SG&A): This includes the costs for a targeted, specialty sales force, marketing and medical education initiatives, and corporate overhead.

- Profitability Analysis: The model generates annual projections for key profitability metrics, including Gross Margin, EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization), and Net Income.

The table below provides a high-level summary of the projected 10-year financial performance.

Table 3: Pro-Forma 10-Year ROI Projection Summary

| Metric | Year 1 | Year 3 | Year 5 | Year 7 (Peak) | Year 10 |

| Units Sold (Millions) | 5 | 20 | 45 | 60 | 50 |

| Gross Revenue | Low | Moderate | High | Peak | Declining |

| Net Revenue (After Rebates) | Low | Moderate | High | Peak | Declining |

| COGS | Very Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gross Margin | High | High | High | High | High |

| SG&A Expenses | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| EBITDA | Negative | Positive | High | Peak | High |

| Cumulative Cash Flow | Negative | Breakeven | Positive | High | Very High |

| Key Financial Outcomes | |||||

| Net Present Value (NPV) | Positive | ||||

| Internal Rate of Return (IRR) | >25% | ||||

| Payback Period | ~4-5 Years |

7.2 ROI Calculation and Sensitivity Analysis

The integrated model demonstrates that the project has the potential to be highly profitable, generating a positive NPV and an IRR that would typically exceed the hurdle rate for such an investment.

However, these outcomes are highly dependent on several critical assumptions. A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of changes in these key variables on the project’s NPV. The results confirm that the project’s financial success is most sensitive to the following factors, listed in order of impact:

- Achieved Net Price Per Unit (Market Access Risk): A 10% decrease in the net price realized from payers has the most significant negative impact on the NPV. This underscores that successful price negotiation and reimbursement are the most critical commercial activities.

- Peak Market Share (Commercial Risk): The ability to effectively compete against the “loose-dose” generic standard of care and achieve the projected peak market share is the second most impactful variable.

- Clinical Trial Cost (Regulatory Risk): Variations in the upfront R&D cost have a substantial impact. If the FDA were to require a clinical program at the high end of the estimated range ($50M+), the project’s IRR would decrease significantly, extending the payback period.

- Length of Market Exclusivity (IP Risk): The model assumes a 10-year period of market protection based on new patents. If patent challenges were to shorten this period, the tail end of the revenue stream would be truncated, reducing the total return.

7.3 Final Recommendations and Risk Mitigation

Investment Thesis Summary

The development of a generic FDC analgesic is a high-risk, high-reward venture that seeks to apply a branded pharmaceutical strategy to commodity products. The investment thesis is predicated on the ability to leverage a streamlined regulatory pathway (505(b)(2)) to create a clinically differentiated product that can be protected by new intellectual property, thereby commanding premium pricing and generating a high-margin revenue stream for a decade or more. The financial analysis confirms that, if executed successfully, the project offers a compelling return on investment.

Go/No-Go Criteria

Given the significant risks, a phased investment approach is recommended. The most critical uncertainty is the scope of the clinical program required by the FDA. Therefore, the primary strategic gate for this project is the Pre-IND Meeting. A definitive “Go” decision to commit to the full, multi-million-dollar clinical development program should be made only if the following criterion is met:

- The sponsor receives written feedback from the FDA confirming that a single, well-designed factorial clinical trial (consistent in size and scope with the mid-range cost estimate of this report) is sufficient to satisfy the Combination Rule and support an NDA submission.

Risk Mitigation Plan

A proactive risk mitigation strategy must be implemented from the outset:

- Regulatory Risk: Engage world-class regulatory consultants with specific, proven experience in 505(b)(2) FDC submissions. Their expertise is critical for designing a clinical plan that is both scientifically robust and maximally efficient, increasing the probability of a favorable outcome at the pre-IND meeting.14

- Market Access Risk: Do not wait until after approval to engage with payers. Begin developing the pharmacoeconomic value dossier and conducting preliminary, informal discussions with payer advisors in parallel with Phase 2/3 clinical development. This allows the value story to be refined and tested early.

- Intellectual Property Risk: File patent applications as early as feasible. The patent strategy should focus on claims that are supported by data demonstrating synergy or unexpected results from the clinical program, as this provides the strongest defense against the challenge of obviousness.15

Concluding Statement

The strategic opportunity to create a novel FDC analgesic from generic components is both viable and financially attractive. The pathway is fraught with significant regulatory, commercial, and IP challenges, but these risks are well-defined and can be mitigated through expert execution and strategic planning. The initial investment to advance the project through the pre-IND meeting stage is justified by the scale of the potential return. A final commitment to full development should be contingent on achieving alignment with the FDA on a manageable clinical pathway, which will serve as the definitive validation of the project’s feasibility and the catalyst for unlocking its substantial value.

Works cited

- (PDF) Clinical pharmacology and rationale of analgesic combinations, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10727454_Clinical_pharmacology_and_rationale_of_analgesic_combinations

- Parenteral Ready-to-Use Fixed-Dose Combinations Including NSAIDs with Paracetamol or Metamizole for Multimodal Analgesia—Approved Products and Challenges – MDPI, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/16/8/1084

- Making a case for a fixed dose combination drug strategy | Pfizer CentreOne, accessed October 2, 2025, https://pfizercentreone.com/about-us/resources/making-case-fixed-dose-combination-drug-strategy

- Fixed-Dose Combination Formulations in Solid Oral Drug Therapy: Advantages, Limitations, and Design Features – MDPI, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/16/2/178

- Fixed-dose combination | Cambrex, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.cambrex.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/cambrex-whitepaper-fixed-dose-combinations.pdf

- The Place of the Fixed-Dose Tramadol/Paracetamol Combination in Pain Management | Open Access Journals – Research and Reviews, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.rroij.com/open-access/the-place-of-the-fixeddose-tramadolparacetamolcombination-in-pain-management-.php?aid=86446

- Fixed-dose combinations for emerging treatment of pain | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221965036_Fixed-dose_combinations_for_emerging_treatment_of_pain

- Fixed Dose Versus Loose Dose: Analgesic Combinations – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed October 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9894647/

- Tramadol/Diclofenac Fixed-Dose Combination: A Review of Its Use in Severe Acute Pain, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.springermedizin.de/tramadol-diclofenac-fixed-dose-combination-a-review-of-its-use-i/17710998

- Oral Analgesics for Acute Dental Pain, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/oral-analgesics-for-acute-dental-pain

- Full article: Ibuprofen/acetaminophen fixed-dose combination as an alternative to opioids in management of common pain types – Taylor & Francis Online, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00325481.2024.2382671

- Fixed-dose combination: Considerations for design, formulation, manufacturing and analysis, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/sponsored/fixed-dose-combination-considerations-for-design-formulation-manufacturing-and-analysis/

- What Is 505(b)(2)? | Premier Consulting, accessed October 2, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/what-is-505b2/

- FDA’s 505(b)(2) Explained: A Guide to New Drug Applications, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.thefdagroup.com/blog/505b2

- A Strategic Guide to Patenting Drug Combinations – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/successfully-patenting-drug-combinations-strategies-and-challenges/

- Advantages and Challenges of Fixed Dose Combination – Longdom Publishing, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.longdom.org/open-access/advantages-and-challenges-of-fixed-dose-combination-104494.html

- Not All Fixed Dose Combinations (FDCs) are Equal – IQVIA, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/not-all-fixed-dose-combinations-are-equal.pdf

- Pain medicines | Canadian Cancer Society, accessed October 2, 2025, https://cancer.ca/en/treatments/side-effects/pain/pain-medicines

- Opioids: Brand names, generic names & street names – ASAM, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/education-docs/opioid-names_generic-brand-street_it-matttrs_8-28-17.pdf?sfvrsn=7b0640c2_2

- Pain Relievers – MedlinePlus, accessed October 2, 2025, https://medlineplus.gov/painrelievers.html

- Tackling challenges in the development of fixed-dose combinations – PharmTech, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.pharmtech.com/view/tackling-challenges-development-fixed-dose-combinations

- Global Oral Solid Dosage Manufacturing Market Report, [2035] – Roots Analysis, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.rootsanalysis.com/reports/oral-solid-dosage-manufacturing-market.html

- Oral Solid Dosage Pharmaceutical Formulation – Research and Markets, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/global-oral-solid-dose-market

- Challenges of fixed dose combination products development – ResearchGate, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287947895_Challenges_of_fixed_dose_combination_products_development

- Challenges and Opportunities in Achieving Bioequivalence for Fixed-Dose Combination Products – PMC, accessed October 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3385830/

- U.S. Oral Solid Dosage Contract Manufacturing Market, 2030 – Grand View Research, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-oral-solid-dosage-contract-manufacturing-market-report

- Oral solid dose formulation and process development – CPI Markets, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www2.uk-cpi.com/markets/pharma/oral-solid-dose-formulation-and-process-development

- Understanding the 505(b)(2) Pathway | Pharmacy Times, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/understanding-the-505-b-2-pathway

- Fixed-Combination Drug Products: Are Phase 2 And 3 Studies …, accessed October 2, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/fixed-combination-drug-products-phase-2-3-studies-really-necessary/

- Using the 505(b)(2) Pathway to Streamline Regulatory Approval for Combination Products, accessed October 2, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/505b2-pathway-regulatory-combination-products/

- The 505(b)(2) Pathway: Unlocking a Hybrid Strategy for Drug …, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-505b2-drug-patent-approval-process-uses-and-potential-advantages/

- Beyond the Cliff: How Generic Drug Makers Can Forge Value and Market Exclusivity with the 505(b)(2) Pathway – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/why-generic-drug-makers-may-benefit-from-505b2-approval/

- 505(b)(1) vs 505(b)(2): Understanding the Key Differences in FDA Drug Approval Processes, accessed October 2, 2025, https://vicihealthsciences.com/505b1-vs-505b2/

- FDA Proposed Rule on Fixed-Combination and Co-Packaged Drugs – Duane Morris, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.duanemorris.com/alerts/fda_proposed_rule_on_fixed-combination_and_co-packaged_drugs_0316.html

- Fixed dose drug combinations (FDCs): rational or irrational: a view point – PMC, accessed October 2, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2432494/

- Maximizing Potential, Minimizing Time, Cost, & Risk: Mastering 505(b)(2) Development Strategy – Premier Research, accessed October 2, 2025, https://premier-research.com/webinars/maximizing-potential-minimizing-time-cost-risk-mastering-505b2-development-strategy-on-demand/

- 505(b)(2) Approval Times: The Real Scoop | Premier Consulting, accessed October 2, 2025, https://premierconsulting.com/resources/blog/505b2-approval-times-the-real-scoop/

- 505(b)(1) versus 505(b)(2): They Are Not the Same – Premier Research, accessed October 2, 2025, https://premier-research.com/perspectives/505b1-versus-505b2-they-are-not-the-same/

- The impact of the API on the cost price of generic medicine – Pharmaoffer.com, accessed October 2, 2025, https://pharmaoffer.com/blog/impact-of-api-on-medicine-price/

- Estimated costs of production and potential prices for the WHO Essential Medicines List, accessed October 2, 2025, https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/1/e000571

- U.S. Pain Management Drugs Market Size and Growth, Statistics 2024 to 2033 – BioSpace, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/u-s-pain-management-drugs-market-size-and-growth-statistics-2024-to-2033

- U.S. Pain Management Drugs Market Size | Companies – Nova One Advisor, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.novaoneadvisor.com/report/us-pain-management-drugs-market

- Pain Management Drugs Market 2025 Rising OTC Demand, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.towardshealthcare.com/insights/pain-management-drugs-market-sizing

- Analgesics Market Size, Share And Growth Report, 2030 – Grand View Research, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/analgesics-market-report

- The 505(b)(2) Playbook: A Strategic Guide to Portfolio Management, Clinical Innovation, and Market Dominance – DrugPatentWatch, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/integrating-clinical-trials-and-505b2-pathway-into-pharmaceutical-portfolio-management-and-generic-launch-strategy/

- Fixed dose drug combinations – are they pharmacoeconomically sound? Findings and implications especially for lower – University of Strathclyde, accessed October 2, 2025, https://pureportal.strath.ac.uk/files/101143836/Godman_etal_ERPOR_2020_Fixed_dose_drug_combinations_are_they_pharmacoeconomically.pdf

- Regulatory and Reimbursement Considerations – Developing Multimodal Therapies for Brain Disorders – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424616/

- State of Mississippi, accessed October 2, 2025, https://medicaid.ms.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/SPA-17-0002-Pages-Proposed.pdf

- Spotlight on Prescription Drug Pricing in Q1 2024 Trends – Segal, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.segalco.com/consulting-insights/spotlight-on-prescription-drug-pricing-in-q1-2024-trends

- Practices Face Challenges When Manufacturers Turn to Code 505(b)(2), accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.targetedonc.com/view/practices-face-challenges-when-manufacturers-turn-to-code-505-b-2-