The pharmaceutical landscape is, without a doubt, a dynamic and often bewildering domain. The headlines are consistently captured by the monumental breakthroughs of biologics—monoclonal antibodies, gene therapies, and cell-based treatments that command astronomical price tags and promise personalized, curative medicine. This narrative, while compelling and deeply impactful, has created a common misconception that small-molecule drugs are a legacy business, a declining relic of a bygone era. A closer, data-driven examination, however, reveals a profoundly different reality. While biologics rightly earn their accolades, the small molecule remains the bedrock of global healthcare, a quiet but powerful engine of innovation that continues to treat billions of patients worldwide and holds immense strategic value for those who understand its true potential.

This report is a deep dive into that strategic potential. It moves beyond the simplistic “small molecule vs. biologic” dichotomy to explore a more nuanced truth: that the two modalities are not in a zero-sum competition, but rather are complementary forces shaping the future of medicine. For pharmaceutical executives, R&D leaders, IP professionals, and investors, understanding this duality is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for turning verifiable, hard data into a decisive competitive advantage.

The Quiet Giants: Re-Evaluating the Small Molecule Narrative

At a glance, the pharmaceutical market seems to be a story of biologics’ explosive growth. The global biologics market was estimated at $348.03 billion in 2022, with projections to reach over $620.31 billion by 2032, representing a noteworthy compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6% over the forecast period.1 This expansion is a testament to the revolutionary impact of these therapies in treating complex diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders.2

Yet, the parallel narrative of the small molecule market is equally compelling, albeit with less fanfare. The global small molecule active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) market was valued at an astonishing $194.96 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach approximately $331.56 billion by 2034, with a robust CAGR of 5.45% from 2025 to 2034.1 Other analyses place the 2024 value at $194.7 billion, growing at a 5.8% CAGR to reach $341.6 billion by 2034.3 Regardless of the specific numbers, the conclusion is consistent: this is a vast, stable, and growing market that serves as the foundation of the pharmaceutical industry.

The Unsung Dominance of Small Molecules

The global dominance of small molecules is undeniable. In 2023, these drugs still comprised approximately 60% of total pharmaceutical sales, with a global market value of around $550 billion.2 They are the standard for managing widespread chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and infections, where their affordability and accessibility are paramount.2 For the business development and investment professional, this stability represents a significant strategic asset. While a novel biologic may offer a high-risk, high-reward profile, the small molecule market provides a foundation of predictable, scalable products that can generate reliable revenue for decades.

This is particularly true for therapeutic areas that have been the traditional strongholds of small molecule innovation. The oncology segment, for example, accounted for a major market share of 27% in 2024, driven by the continuous development of novel small-molecule cancer therapies.1 Similarly, the cardiovascular segment dominated the market with a 20.6% share in 2024, a reflection of the rising prevalence of heart diseases and the continued demand for advanced medical technologies to treat them.3 The existence of a steady, multi-hundred-billion-dollar market with robust, predictable growth is not a story of decline; it is a story of enduring commercial power and parallel expansion that complements the high-profile narrative of biologics.

The Anatomy of a Molecule: A Definitive Comparison

The commercial and clinical distinction between small molecules and biologics is not accidental; it is a direct consequence of their fundamental physical and chemical properties. Small molecules are chemically synthesized compounds, typically composed of 20 to 100 atoms with a molecular mass of less than 1 kilodalton ($<$1 kDa).4 In contrast, biologics are large, complex molecules, such as proteins or nucleic acids, that are produced from living organisms.5 They can contain anywhere from 5,000 to 50,000 atoms per molecule, making them orders of magnitude larger than their small-molecule counterparts.4

This fundamental difference in size and structure dictates their interaction with the human body. Because of their compact size, small molecules can be designed to cross cell membranes and, critically, the blood-brain barrier.7 This opens up an immense range of intracellular and central nervous system (CNS) targets that are inaccessible to the vast majority of biologics. Furthermore, their small size makes them suitable for most forms of administration, but they are most often administered orally.7 This seemingly simple detail is a profound clinical and commercial advantage. Patient adherence to a medication regimen is a critical factor for success, and the oral administration of a pill or tablet is the method most preferred by patients, particularly for chronic conditions.7 This “pill vs. injection” dichotomy is a primary reason why small molecules, despite their lower revenue per dose, quietly treat billions of patients worldwide. It directly links the science of molecular weight to the business outcome of patient convenience and, ultimately, market penetration.

The Economic Engine: R&D, Investment & Manufacturing

The conventional wisdom in biopharma often suggests that biologics represent a superior investment opportunity due to their higher returns. While financial models have reported a higher internal rate of return (IRR) for biologics projects, and the net present value (NPV) for an average preclinical biologic is estimated at $104 million compared to $37 million for a small molecule, the reality of the market tells a more complex story.8 Despite this apparent financial advantage, small-molecule companies surprisingly comprise the majority of the total IPO pool.8

The Surprising Economics of Drug Development

There is a clear disconnect between what financial models predict and how investors actually behave. The reason for this paradox lies in the different risk profiles and time horizons associated with each modality. While the long-term, risk-adjusted value of a biologic might be higher, the data suggests that a small-molecule program may be perceived as proceeding “more quickly or more economically through discovery and early development”.8 This perception, whether fully borne out by the numbers or not, is a powerful driver of investor behavior. A small-molecule startup can offer a quicker path to a clinical milestone, a faster time-to-market, or a more attractive runway for a strategic exit, even if the ultimate revenue potential of the individual drug is lower than a blockbuster biologic. This contrasts sharply with the often multi-billion-dollar, longer-term commitment required to bring a biologic to market.9 For a venture capital firm or an investor with a shorter time horizon, the small molecule pipeline offers a compelling blend of proven technology and a more manageable path to a return on investment.

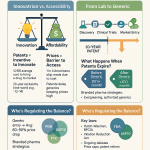

From Lab Bench to Billions: Manufacturing as a Strategic Advantage

The economic discussion of small molecules cannot be complete without a deep dive into manufacturing. Here, the strategic advantages of small molecules are perhaps most pronounced. The average production cost for a small-molecule drug is approximately $5 per pack, in stark contrast to the $60 per pack for a biologic.10 Another analysis shows that a daily dose of a biologic costs an average of 22 times more than that of a small molecule.11 This immense cost disparity is not just a footnote; it is a fundamental driver of market dominance and patient accessibility, especially for generic drugs.

The relative simplicity and stability of small molecules allow them to be manufactured through well-established chemical synthesis methods.6 This process is highly scalable and reproducible, enabling the large-scale production of generic drugs at a fraction of the cost of their brand-name counterparts. This regulatory and manufacturing efficiency is the fundamental source of the cost savings associated with generic drugs. The impact of this on the healthcare system is monumental. In the U.S., generic drugs account for over 80% of all prescriptions filled and provided a record-breaking $445 billion in savings in 2023 alone.12 This economic efficiency is a direct consequence of the small molecule’s inherent physicochemical properties and is a core component of their enduring relevance.

This dynamic also explains the critical and growing role of Contract Development and Manufacturing Organizations (CDMOs). With the outsourced manufacturing segment accounting for the largest market share in 2024 at 61.8%, CDMOs are no longer just service providers; they are strategic partners.3 They provide the specialized expertise and infrastructure required to handle complex, high-potency APIs and enabling formulations, which are becoming increasingly common in the modern small molecule pipeline.14 The race to develop a more effective oral GLP-1, for example, will require advanced formulation expertise, increasing the demands on CDMOs to create intellectual property and add value beyond simple manufacturing.14

The Strategic Fortress: Intellectual Property as the Core Asset

In the high-stakes game of pharmaceutical development, intellectual property is not just a legal construct; it is the primary engine of value creation and the core driver of competitive advantage. The IP landscape for small molecules and biologics is a study in contrasts, a reflection of different legal frameworks and distinct strategic approaches. Understanding these differences is paramount for any business professional aiming to protect a portfolio or challenge an existing market leader.

The Differential Landscape of IP Protection

The U.S. legal system, through a series of legislative acts, has established a differential set of protections for each drug class. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, new small-molecule drugs are granted up to 5 years of statutory exclusivity, a period during which the FDA cannot review applications for generic versions.15 By contrast, the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA) grants biologics a more substantial 12 years of exclusivity before a biosimilar can be approved for marketing.15

This difference in statutory exclusivity is further compounded by the realities of patent protection. A comprehensive analysis of new drugs approved from 2009 to 2023 found that biologics were protected by a median of 14 patents, compared to just 3 patents for small-molecule drugs.15 This dense collection of patents around a single product is often referred to as a “patent thicket,” and its primary purpose is to create a defensive moat that deters competition by making the legal challenge prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.16

“Biologics were protected by a median of 14 patents (IQR: 5-24 patents) compared to 3 patents (IQR: 2-5 patents) for small-molecule drugs (P<0.001). The median time to biosimilar competition was 20.3 years… compared to 12.6 years… for small-molecule drugs.”

— Source: Findings from a study on FDA-approved therapeutic agents, 2009-2023.15

This data reveals a powerful truth: the legislative premise that biologics require extended exclusivity due to weaker patent protection is not supported by the facts.15 In practice, originator companies use the patent system itself to create multi-layered thickets that extend their market exclusivity well beyond the statutory period. The median time to biosimilar competition for a biologic is a staggering 20.3 years, while for a small molecule it is 12.6 years.15 For the challenger—the generic or biosimilar manufacturer—this means navigating a minefield of legal challenges, where the invalidation of a single patent may not be enough to open the door to competition.16

This is precisely where the strategic value of comprehensive patent intelligence, such as that offered by DrugPatentWatch, becomes indispensable. Such platforms provide the tools to systematically analyze a competitor’s patent filings, identify key patents, and assess the strength of a patent thicket. This analysis can inform a strategic decision on which patents to challenge via administrative pathways like inter partes review (IPR), a process that has been used by biosimilar manufacturers to invalidate patents and facilitate market entry.17

The Art of the Deal: M&A Due Diligence and Patent Intelligence

In pharmaceutical mergers and acquisitions, the value of a company often resides not in its physical assets, but in its intangible intellectual property.18 A robust patent portfolio for a key drug asset can grant a legal monopoly for decades, creating a period of market exclusivity where the owner can recoup massive R&D investments and generate substantial profits without direct generic competition.19

Therefore, patent due diligence in an M&A context is not a routine legal check; it is a strategic operation with three core objectives: mitigating risk, enabling accurate valuation, and ensuring strategic alignment.18 The investigation must go beyond simply verifying patent validity to asking a series of deeper questions: How strong is the patent? How broad is the protection? What is the true remaining duration of market exclusivity when secondary patents and regulatory exclusivities are factored in? This includes scrutinizing the “crown jewel” composition-of-matter (CoM) patents, which are the most valuable, as well as the more layered method-of-use (MoU) patents that cover a drug’s specific application.19 A thorough analysis can uncover hidden liabilities, such as weak claims or a history of litigation that could signal an easy target for competitors.19 Conversely, it can also reveal unforeseen opportunities, such as unlisted patents on a novel formulation or method of use that can be leveraged to increase the asset’s value post-acquisition. The ability to identify these nuances is a core competitive advantage for a savvy M&A team.

Real-World Case Studies in Small Molecule Strategy

The theoretical concepts of market dynamics and intellectual property become concrete when viewed through the lens of real-world case studies. The stories of blockbuster small molecules are not just tales of scientific achievement; they are masterclasses in commercial strategy, demonstrating how innovation, legal acumen, and lifecycle management can transform a single drug into a multi-billion-dollar franchise.

The Lipitor Masterclass: Navigating the Patent Cliff

Pfizer’s Lipitor (atorvastatin) is perhaps the most famous example of a small molecule blockbuster. Over 14 years, it generated more than $125 billion in revenue for the company, becoming the world’s most-sold drug and a symbol of pharmaceutical dominance.21 When its primary U.S. patent expired in 2011, the industry watched with bated breath to see how Pfizer would manage the inevitable revenue plunge.

The company’s strategy was a textbook example of sophisticated lifecycle management. Before the patent expired, Pfizer employed a multi-pronged defense that included legal delaying tactics and aggressive direct-to-consumer marketing to solidify the brand’s reputation.21 However, the most effective strategies were executed post-expiry. Pfizer launched an “authorized generic” version of Lipitor through a partnership, a strategic maneuver that allowed them to retain a significant portion of the revenue and prevent a complete market share collapse during the crucial 180-day generic exclusivity period.21 The company also implemented a sophisticated rebate strategy for its branded product, offering coupons and deals to insurance plans and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to make Lipitor’s cost to the patient and payer competitive with its new generic rivals.21

The Lipitor story proves that for a mature small molecule, the game is not over when the primary patent expires. It becomes a new, multifaceted competition based on legal, marketing, and commercial strategies. It is a powerful illustration of how a deep understanding of the regulatory environment and a willingness to use every available tool can manage the challenges of patent expiry and extend a drug’s profitability for years.21

The Viagra Story: A Serendipitous Pivot

Pfizer’s Sildenafil, marketed as Viagra, is a classic example of serendipity in drug discovery. The compound was originally developed in the late 1980s to treat angina, a heart condition.23 During a Phase I clinical trial in the early 1990s, an observant nurse noted that many of the male participants were lying on their stomachs, a sign of embarrassment related to an unexpected side effect: erectile dysfunction.24

This observation led to a radical pivot in the drug’s development. The company recognized the massive commercial potential and successfully pivoted the drug’s use, securing new method-of-use patents and creating a multi-billion-dollar franchise.24 The very same compound, sildenafil, was later approved to treat a heart condition called pulmonary arterial hypertension and is sold under the brand name Revatio.24

This story highlights a key advantage of small molecules: their ability to interact with multiple targets and penetrate different physiological barriers.4 This versatility can lead to the discovery of new indications, which, in turn, can be protected by new method-of-use patents.20 The Viagra story demonstrates the enduring value of a strong IP portfolio that extends beyond the initial composition-of-matter patent. The ability to layer new patents on top of an existing drug is a core component of “evergreening” and a powerful strategy for extending a franchise’s commercial life. It shows how a single, well-understood molecule can be a platform for continuous innovation.

The Regulatory Edge: Leveraging ICH Q12

Lifecycle management is not exclusively a legal and marketing discipline; it is also a regulatory and manufacturing one. A case study on a small molecule product illustrates how a company successfully used the ICH Q12 framework to streamline post-approval manufacturing changes, an area that has historically been a significant source of delay and inefficiency.25

The company leveraged the principles of Quality by Design (QbD) to define “Established Conditions” in its regulatory application, which are legally binding details considered necessary to assure product quality.25 This prospective life-cycle management planning allowed the company to manage and implement post-approval changes in a more predictable and efficient manner. For example, by providing sufficient data, they were able to get approval to report the potential future omission of a purification step as a minor change, known as a “Notification Moderate,” rather than the time-consuming and costly “Prior Approval Supplement” that would have otherwise been required.25

This demonstrates how the relative simplicity and predictability of small molecule synthesis, compared to the complexity and variability of biologics, make them ideal candidates for this kind of process optimization.6 By reducing waste and improving efficiency at the manufacturing level, these seemingly minor changes contribute directly to a lower cost of goods and higher profit margins over the product’s long commercial life. It shows that a deep understanding of manufacturing and regulatory pathways is just as important as a robust patent strategy for creating long-term value.

The Future of Medicine is Small

While the high-profile narrative of biologics may suggest small molecules are a legacy business, the reality is that the field is undergoing a profound and exciting reinvention. Far from being a mature space, small molecules are at the cutting edge of modern drug discovery, driven by revolutionary new modalities and a fundamental shift in the way R&D is conducted.

From Undruggable to Unstoppable: The Next Wave of Small Molecule Innovation

The next wave of small molecule innovation is not focused on simply inhibiting enzymes or receptors. It is centered on entirely new mechanisms of action, such as those employed by Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues.26 These molecules are designed to exploit the cell’s natural protein degradation machinery, the ubiquitin-proteasome system, to selectively eliminate unwanted or harmful proteins rather than just inhibiting their function.27

The most profound advantage of these new modalities is their potential to target previously “undruggable” proteins.27 For decades, many disease-driving proteins have been considered impossible to target with traditional small-molecule inhibitors because they lack a clear binding pocket. PROTACs circumvent this problem by acting as a bridge between the target protein and a ligase, a process that can lead to a catalytic effect where a single PROTAC molecule can degrade many target protein molecules.27 This, in turn, can lead to efficacy at much lower concentrations, potentially resulting in fewer off-target effects and a more favorable safety profile.27 The growing demand for these complex small molecule APIs, particularly in areas like Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) and GLP-1 receptor agonists, is a powerful indicator that the small molecule is not just a legacy product but an integral part of the future of medicine.29

AI, Automation, and the Reinvention of Discovery

The high cost and long timelines of drug development have always been a major headwind for the pharmaceutical industry. However, advancements in technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are fundamentally changing this dynamic, particularly in the small molecule space.12 AI algorithms can analyze vast datasets to identify new drug targets and optimize molecular structures at a fraction of the traditional cost and time, dramatically improving “hit rates” and expediting the discovery process.12

This acceleration directly addresses the high-risk, high-cost nature of drug development. By improving efficiency and reducing timelines, AI makes small molecules an even more attractive proposition for R&D teams and investors. For the business development professional, this presents a unique opportunity to partner with and invest in companies that are leveraging these new technologies to unlock previously inaccessible targets, creating a powerful new playbook for small molecule innovation.14 The future of medicine is not exclusively biologic or small molecule; it is a convergence, where the precision of new technologies is applied to the fundamental, versatile power of the small molecule.

Key Takeaways

- Small Molecules Remain a Market Giant: The small molecule API market is a massive, multi-hundred-billion-dollar industry with robust, predictable growth that serves as the enduring foundation of global healthcare, quietly treating billions of patients for widespread chronic conditions.

- Manufacturing is a Core Strategic Asset: The cost-effectiveness, scalability, and stability of small molecule manufacturing provide a profound competitive advantage. This efficiency enables the development of affordable generic drugs that drive a significant portion of healthcare savings.

- IP is a Game of Leverage: The IP landscape for small molecules is complex, with regulatory exclusivity and patent thickets creating a nuanced environment. Strategic patent due diligence and a deep understanding of different claim types are essential for creating value in M&A and protecting market position.

- Innovation is Reinvigorating the Field: New small molecule modalities like PROTACs and molecular glues are at the cutting edge of medicine, offering the potential to target previously “undruggable” proteins. Combined with the power of AI and automation, these advances are breathing new life into the small molecule pipeline and opening up new therapeutic frontiers.

- The Future is Convergent: The most successful pharmaceutical companies will not choose between small molecules and biologics. They will leverage the unique strengths of each modality and the power of technology to address a wider range of diseases and create enduring value for patients and shareholders alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why, if biologics have a higher NPV, do small molecule companies still dominate the IPO market?

The apparent paradox stems from a difference in risk profiles and time horizons. While a financial model may show a higher long-term, risk-adjusted value for biologics, investors often favor small molecules due to a perception of a quicker and more economical path through early development. A small-molecule company can offer a faster path to a clinical milestone or a strategic exit, which can be more appealing to venture capital and investors operating on a shorter timeline, even if the ultimate revenue potential is lower.

2. How can a generic manufacturer navigate a “patent thicket” and what role does patent data play?

A patent thicket is a dense web of patents around a single drug, making it difficult and expensive for competitors to enter the market. A generic manufacturer must conduct comprehensive patent analysis to navigate this landscape. This involves identifying all relevant patents, assessing their legal strength, and deciding which ones to challenge in court or through administrative processes like inter partes review (IPR). Patent data is a critical intelligence source, providing detailed information on a competitor’s R&D priorities, filing patterns, and legal challenges. This information allows a company to plan its market entry strategy, anticipate legal risks, and focus its resources on challenging the most vulnerable patents.

3. Given the rise of biologics, how do you see the role of CDMOs changing in the small molecule space?

The role of CDMOs is evolving from that of a simple manufacturer to a strategic partner. As small molecule R&D increasingly focuses on more complex APIs, such as those for ADCs and new modalities, pharmaceutical companies are relying on CDMOs for specialized expertise in formulation, bioavailability enhancement, and handling highly potent compounds. CDMOs are also adding value by offering services that strengthen their clients’ IP positions and optimize the manufacturing process for long-term efficiency and scalability, thereby helping companies reduce costs and add value throughout the product lifecycle.

4. What are the key strategic advantages of a small molecule drug that has been “repurposed” for a new indication?

The repurposing of an existing small molecule for a new indication offers several key strategic advantages. First, it significantly reduces R&D costs and timelines, as the drug’s safety profile is already well-understood. Second, it allows a company to secure new method-of-use patents, thereby extending the commercial life of the drug and creating a new revenue stream. Third, it leverages the drug’s inherent physicochemical properties, such as its ability to cross physiological barriers like the blood-brain barrier, which may be a significant advantage over other therapeutic modalities for the new indication.

5. Are new modalities like PROTACs and molecular glues the future of small molecules, or are they a niche market?

New modalities like PROTACs and molecular glues are not just a niche market; they are at the forefront of the next wave of small molecule innovation. Their ability to target and degrade previously “undruggable” proteins represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, opening up a vast new landscape of potential therapeutic targets. While still early in their development, these modalities are garnering significant investment and attention, suggesting they will become a critical component of the small molecule pipeline, particularly in areas like oncology, where their precise mechanism of action offers a powerful alternative to traditional therapies.

Works cited

- Small Molecule API Market Size to Reach USD 331.56 Bn by 2034 – BioSpace, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/press-releases/small-molecule-api-market-size-to-reach-usd-331-56-bn-by-2034

- Biologics vs. Small Molecule Drugs: Market Share and Growth Trends (Latest Data), accessed September 22, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/biologics-vs-small-molecule-drugs-market-share-and-growth-trends-latest-data

- Small Molecule API Market Size & Share Report, 2025 – 2034, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/small-molecule-api-market

- Small Molecules vs. Biologics: Key Drug Differences – Allucent, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.allucent.com/resources/blog/points-consider-drug-development-biologics-and-small-molecules

- Navigating the Complexities of Biologic Drug Patents – PatentPC, accessed September 22, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/navigating-complexities-biologic-drug-patents

- Biologics vs Small Molecules – An Overview – Upperton Pharma Solutions, accessed September 22, 2025, https://upperton.com/biologics-vs-small-molecules-key-considerations-in-drug-development/

- Are small-molecule drugs having their big moment? – Definitive Healthcare, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/small-molecule-drug-rise

- Investigating investment in biopharmaceutical R&D – PMC, accessed September 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5100010/

- Research and development investments for biologics independently developed by US biotechnology startups, 2017–2023 – PMC, accessed September 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12290397/

- What Does—and Does Not—Drive Biopharma Cost Performance – Boston Consulting Group, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2017/biopharmaceuticals-operations-what-does-and-does-not-drive-biopharma-cost-performance

- Major differences between biologics and small molecules [10] – ResearchGate, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Major-differences-between-biologics-and-small-molecules-10_tbl1_347116457

- Small Molecule Drug Discovery Market Forecast, 2025-2032 – Coherent Market Insights, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.coherentmarketinsights.com/market-insight/small-molecule-drug-discovery-market-5214

- The Impact of Generic Drugs on Healthcare Costs – DrugPatentWatch, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-impact-of-generic-drugs-on-healthcare-costs/

- Pharma trends and predictions for 2025: An incoming CEO’s perspective | pharmaphorum, accessed September 22, 2025, https://pharmaphorum.com/rd/pharma-trends-and-predictions-2025-incoming-ceos-perspective

- 1 Differential Legal Protections for Biologics vs. Small-Molecule …, accessed September 22, 2025, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/126180/1/2024.08.03_manuscript.pdf

- BILL TO ADDRESS PATENT THICKETS, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.welch.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Welch.Braun_.Klobuchar-Patent-bill.pdf

- Changes In Biologic Drug Revenues After Administrative Patent Challenges – Health Affairs, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2024.00504

- A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmaceutical Patent Due Diligence in Mergers & Acquisitions, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/ma-patent-due-diligence-comprehensive-guide/

- The Billion-Dollar Question: Using Drug Patent Data as Your Crystal Ball in Pharma M&A Due Diligence – DrugPatentWatch, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-billion-dollar-question-using-drug-patent-data-as-your-crystal-ball-in-pharma-ma-due-diligence/

- What Is the Difference Between Composition and Method-of-Use Claims?, accessed September 22, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/what-is-the-difference-between-composition-and-method-of-use-claims

- (PDF) Managing the challenges of pharmaceutical patent expiry: a …, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309540780_Managing_the_challenges_of_pharmaceutical_patent_expiry_a_case_study_of_Lipitor

- Who holds the patent for Atorvastatin? – Patsnap Synapse, accessed September 22, 2025, https://synapse.patsnap.com/article/who-holds-the-patent-for-atorvastatin

- Sildenafil – Wikipedia, accessed September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sildenafil

- Viagra’s famously surprising origin story is actually a pretty common way to find new drugs, accessed September 22, 2025, https://qz.com/1070732/viagras-famously-surprising-origin-story-is-actually-a-pretty-common-way-to-find-new-drugs

- Case Study: Facilitating Efficient Life-Cycle Management via ICH Q12, accessed September 22, 2025, https://ispe.org/pharmaceutical-engineering/case-study-facilitating-efficient-life-cycle-management-ich-q12

- Next generation therapeutics – AstraZeneca, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.astrazeneca.com/r-d/next-generation-therapeutics.html

- A beginner’s guide to PROTACs and targeted protein degradation …, accessed September 22, 2025, https://portlandpress.com/biochemist/article/43/5/74/229305/A-beginner-s-guide-to-PROTACs-and-targeted-protein

- PROTAC® Degraders & Targeted Protein Degradation – Tocris Bioscience, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.tocris.com/product-type/targeted-protein-degradation

- Future of small molecule manufacturing in 2025 | Axplora, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.axplora.com/dcat-api-article-2025/

- Small molecules – AstraZeneca, accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.astrazeneca.com/r-d/next-generation-therapeutics/small-molecule.html