In pharmaceutical development timing isn’t just a factor; it’s the fulcrum upon which success or failure teeters. A few months can be the difference between capturing a billion-dollar market and arriving at a party that’s already over. For companies leveraging the sophisticated 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway—a hybrid route that masterfully blends innovation with established science—this temporal precision becomes even more critical. You’re not just racing against the clock; you’re navigating a complex, multi-dimensional chessboard of patents, regulatory exclusivities, and competitive maneuvers.

So, how do you transform this daunting complexity into a competitive advantage? The answer lies not in a crystal ball, but in the meticulous, strategic interpretation of drug patent data. This isn’t about simply looking up an expiration date in the FDA’s Orange Book. It’s about becoming a data-driven oracle, capable of predicting patent litigation landscapes, identifying hidden windows of opportunity, and ultimately, timing your New Drug Application (NDA) submission to achieve maximum commercial impact.

This article is your comprehensive guide to mastering that art. We will journey deep into the architecture of the 505(b)(2) pathway, dissect the anatomy of pharmaceutical patents, and reveal the advanced strategies that leading companies use to turn data into market dominance. Whether you are a regulatory affairs professional, an IP strategist, a business development executive, or a CEO, the insights that follow will empower you to move beyond reactive tactics and embrace a proactive, data-informed approach to your 505(b)(2) filings. Prepare to learn not just how to use patent data, but how to think with patent data, transforming it from a static list of dates into a dynamic roadmap for success.

Demystifying the 505(b)(2) Pathway: The Strategic Bridge

Before we can weaponize patent data, we must first deeply understand the unique terrain of the 505(b)(2) pathway. It’s often described as a “hybrid” or “bridge” application, but what does that truly mean in practice? Think of it as the pharmaceutical equivalent of building a state-of-the-art skyscraper using a proven, time-tested foundation. You’re not reinventing the wheel (or the concrete), but you are creating something novel and valuable.

What is a 505(b)(2) NDA? A Bridge Between Innovation and Imitation

The 505(b)(2) New Drug Application, established by the Hatch-Waxman Amendments of 1984, is one of three routes to U.S. drug approval. It resides strategically between the full-scale 505(b)(1) NDA for a New Chemical Entity (NCE) and the streamlined 505(j) Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for a generic drug.

A 505(b)(1) application is a monumental undertaking. The sponsor must conduct all the preclinical and clinical studies necessary to prove the drug’s safety and efficacy from scratch. It’s a high-risk, high-cost, decade-plus journey. At the other end of the spectrum, a 505(j) ANDA is for a generic drug that is identical—in active ingredient, dosage form, strength, route of administration, and labeling—to a previously approved brand-name drug, known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). The ANDA applicant primarily needs to prove bioequivalence.

The 505(b)(2) pathway offers a third way. It allows a sponsor to create a differentiated product while relying, in part, on the FDA’s previous findings of safety and effectiveness for an approved drug. This is the core principle: you don’t have to redo every single study yourself. You can reference existing data, which can dramatically reduce the time, cost, and risk of development.

The Core Advantage: Leveraging Existing FDA Findings

The true power of the 505(b)(2) route lies in Section 505(b)(2) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act itself, which allows an application to contain “full reports of investigations of safety and effectiveness” where “the applicant has not obtained a right of reference or use from the person by or for whom the investigations were conducted” [1]. This legal clause is the key that unlocks the value.

Imagine the RLD’s dossier as a vast library of research. A 505(b)(2) applicant gets to check out several volumes from this library (the publicly available data and the FDA’s findings) to support their own application. They only need to conduct the new studies—often called “bridging studies”—necessary to support the specific changes or differences between their proposed product and the RLD.

This creates a powerful value proposition. You can bring a clinically meaningful improvement to market without the gargantuan expense of a full NCE development program.

“The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development pegged the estimated average out-of-pocket cost to develop a new medicine at $1.3 billion, with capitalized costs bringing the total to $2.6 billion in 2013 dollars. More recent estimates suggest this figure is now closer to $3 billion.”— Joseph A. DiMasi, Henry G. Grabowski, Ronald W. Hansen [2]

When viewed against these staggering figures, the appeal of a pathway that leverages existing data becomes profoundly clear. The 505(b)(2) route offers a path to innovation on a more manageable budget, democratizing drug development and fostering competition.

Key Differences from 505(b)(1) (NDA) and 505(j) (ANDA)

To truly grasp the strategic implications, let’s crystallize the differences:

| Feature | 505(b)(1) NDA | 505(b)(2) NDA | 505(j) ANDA |

| Product Type | New Chemical Entity (NCE) | Differentiated product (new dosage, strength, indication, etc.) | Generic equivalent |

| Data Reliance | Full, self-conducted studies | Combination of own studies and reliance on FDA’s findings for an RLD | Reliance on FDA’s findings for an RLD |

| Clinical Studies | Full suite of Phase 1, 2, 3 trials | “Bridging” studies to support the change from the RLD | Bioequivalence (BE) study |

| Market Exclusivity | Eligible for 5-year NCE, 3-year NCI, Orphan, Pediatric | Eligible for 3-year NCI, Orphan, Pediatric | 180-day generic drug exclusivity for the first successful P-IV filer |

| Patent Certification | Not applicable for initial filing | Required (Paragraph I, II, III, or IV) | Required (Paragraph I, II, III, or IV) |

| Development Cost | Very High ($1B+) | Moderate | Low |

| Development Time | 10-15+ years | 3-7 years | 2-4 years |

This table illustrates the unique position of the 505(b)(2) pathway. It’s faster and cheaper than an NCE but allows for product branding, differentiation, and the potential for its own market exclusivity—advantages that are unavailable to a standard generic ANDA.

The Spectrum of 505(b)(2) Applications

The flexibility of the 505(b)(2) pathway is one of its greatest assets. The “change” or “differentiation” from the RLD can take many forms, creating a wide spectrum of opportunities. Common examples include:

- New Dosage Form: Changing a drug from a tablet to an oral film, a patch, or an extended-release capsule. A classic example is Suboxone®, which transitioned from a sublingual tablet to a sublingual film, offering improved characteristics.

- New Strength: Developing a strength that is not currently available for the RLD, which may be beneficial for specific patient populations.

- New Indication: Seeking approval for a new use of an already-approved drug. This is a common strategy for drug repurposing.

- Change in Formulation or Excipients: Altering the inactive ingredients to improve stability, taste, or reduce allergic reactions.

- New Combination Product: Combining two or more approved drugs into a single product for improved convenience and compliance.

- Change in Route of Administration: Moving from an injectable to an oral formulation, for instance.

Each of these changes requires a unique development plan and, crucially, a distinct patent and timing strategy. The choice of which modification to pursue is deeply intertwined with the existing patent landscape of the RLD.

The Central Role of Patent Data in 505(b)(2) Strategy

If the 505(b)(2) pathway is the vehicle, then patent data is the GPS, the satellite imagery, and the weather forecast all rolled into one. It tells you where you can go, what obstacles lie in your path, and when the conditions are most favorable for your journey. Ignoring this data is like setting sail in a storm without a map or compass.

Beyond the Orange Book: A Deeper Dive into Patent Intelligence

For many, “drug patent data” is synonymous with the FDA’s “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” more famously known as the Orange Book [3]. The Orange Book is an essential starting point. It lists approved drug products and identifies the patents and regulatory exclusivities that the RLD holder has asserted cover its drug.

However, viewing the Orange Book as the beginning and end of your patent search is a rookie mistake. It’s merely the cover of the book, not the full story. A robust patent intelligence strategy goes far deeper. It involves:

- Analyzing the patents themselves: Reading the claims to understand precisely what is protected. Does the patent cover the active ingredient, a specific crystalline form (polymorph), the method of use, or the formulation?

- Searching USPTO databases: Uncovering patents and patent applications that are not listed in the Orange Book but could still be relevant and pose a litigation risk.

- Monitoring international patent offices: Understanding the global patent strategy of the innovator, which can provide clues about their U.S. strategy.

- Tracking patent litigation: Keeping tabs on lawsuits involving the RLD’s patents can reveal their strengths, weaknesses, and the innovator’s willingness to settle.

This holistic view transforms static patent listings into a dynamic, predictive tool. It’s the difference between knowing a roadblock exists and knowing its exact location, its size, what it’s made of, and when it’s scheduled to be removed.

Why Timing is Everything: The High Stakes of Market Entry

In the pharmaceutical industry, the timing of your market entry dictates your commercial trajectory. The goal of a 505(b)(2) applicant is often to launch “at-risk” before all patents have expired, or to be the first differentiated alternative to the brand as soon as patent protection wanes.

Consider two scenarios:

- Scenario A: Perfect Timing. You file your 505(b)(2) NDA at a moment that allows you to resolve any patent disputes and gain approval just as a key blocking patent on the RLD expires. You enter the market with a branded, differentiated product, facing limited competition, and can command a premium price. You may even secure your own 3-year market exclusivity, preventing other 505(b)(2) or ANDA applicants from gaining approval for the same change.

- Scenario B: Mistiming. You file too early, triggering a patent infringement lawsuit and a 30-month stay of approval that you weren’t prepared for. By the time you get to market, several ANDA generics have already launched, the price has plummeted, and your “differentiated” product struggles to gain traction. Or, you file too late, and another 505(b)(2) competitor has already beaten you to the punch, captured the “first mover” advantage, and potentially blocked you with their own exclusivity.

As Dr. John LaMattina, former President of Pfizer Global R&D, astutely notes, “The financial rewards in the pharmaceutical industry are skewed to the first two or three players in a new class. Being fourth or fifth to market is a tough way to make a living” [4]. While he speaks of new classes, the principle is equally potent for differentiated follow-on products. The first mover in the post-patent-cliff space sets the new standard.

The Cost of Mistiming: Lost Revenue and Competitive Disadvantage

The financial consequences of poor timing are brutal. Every day a product is delayed from its optimal launch date is a day of lost revenue. For a product with peak sales potential in the hundreds of millions, a six-month delay can mean a loss of tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars.

But the cost isn’t just financial. It’s strategic. Mistiming can lead to:

- Eroded Market Share: Arriving after generics have saturated the market makes it incredibly difficult to convince physicians and payers to choose your premium-priced product.

- Pricing Pressure: The presence of low-cost alternatives severely limits your pricing flexibility.

- Wasted R&D Investment: The capital invested in developing the product may never be fully recouped if the commercial launch falters.

- Damaged Credibility: A failed or significantly delayed launch can damage a company’s reputation with investors and partners.

Therefore, the investment in a sophisticated patent intelligence and timing strategy is not a cost center; it is one of the most critical investments you can make to de-risk your entire 505(b)(2) program.

Building Your Patent Intelligence Arsenal

To execute a winning timing strategy, you need the right tools and a deep understanding of how to use them. Your “patent intelligence arsenal” consists of several key data sources, each with its own strengths and limitations. Assembling a complete picture requires triangulating information from all of them.

Key Data Sources: The FDA’s Orange Book and Beyond

The journey begins with public data, but true mastery requires looking beyond the obvious. Your primary sources will be the FDA and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), but specialized commercial services are often essential for efficiency and deeper insights.

The Indispensable Orange Book: Strengths and Limitations

The Orange Book is the bible for anyone in the generic and 505(b)(2) space. It’s the official register where brand-name companies list the patents they claim cover their drug product, drug substance, or method of use.

Strengths:

- Official Source: It is the definitive list that governs patent certifications in an NDA and the triggering of 30-month stays.

- Key Dates: It provides patent numbers, expiration dates, and information on any patent term extensions (PTE) or pediatric exclusivity.

- Exclusivity Information: It clearly lists regulatory exclusivities like NCE (5-year), NCI (3-year), and Orphan Drug (7-year) exclusivities, which act as non-patent-based market protection.

- Use Codes: For method-of-use patents, it includes FDA-assigned use codes that describe the specific indication covered by the patent.

Limitations:

- Incomplete Picture: The brand company is responsible for submitting patents for listing. They may not list every relevant patent. Patents covering manufacturing processes, for example, are generally not listable but could still be asserted in litigation.

- Lack of Claim Detail: The Orange Book tells you a patent is listed; it doesn’t tell you what the patent claims. Two patents might have the same expiration date, but one might cover the core molecule (very hard to design around) while the other covers a specific manufacturing impurity (potentially easier to avoid).

- No Pending Applications: It does not include information on pending patent applications, which could issue at any time and pose a future threat (the so-called “submarine patents”).

- Static Nature: While updated, it’s a snapshot. It doesn’t provide context on litigation history, validity challenges, or international counterparts.

The Orange Book tells you what the innovator claims. It’s your job to verify, question, and investigate those claims.

USPTO Databases: Unearthing Hidden Gems

The next layer of your investigation is the USPTO’s own databases. This is where you go to read the patents themselves and search for those not listed in the Orange Book. Key resources include:

- Patent Full-Text and Image Database (PatFT): Allows you to search for and view the full text of issued U.S. patents. Here you can analyze the claims, the specification, and the prosecution history.

- Patent Application Full-Text and Image Database (AppFT): Lets you search for published patent applications. This is crucial for identifying potential future threats. Is the innovator trying to patent a new polymorph, a new formulation, or a metabolite of their drug? This database provides the answer.

- Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) End-to-End Search: This is where you find information about challenges to a patent’s validity, such as inter partes review (IPR) proceedings. If a patent listed in the Orange Book is already under attack in a PTAB proceeding, its strength may be questionable.

Diving into USPTO records is non-negotiable. It’s where you find the granular detail that separates a winning strategy from a losing one. For example, by analyzing the “file wrapper” (the public record of communication between the applicant and the patent examiner), you can understand what arguments the innovator used to get the patent, which can reveal potential weaknesses.

Leveraging Specialized Services: The Role of Platforms like DrugPatentWatch

Conducting this level of deep-dive analysis manually is incredibly time-consuming and requires specialized expertise. This is where commercial intelligence platforms become invaluable strategic assets.

While the Orange Book and USPTO databases provide the raw materials, specialized services act as the refinery, turning crude data into high-octane strategic fuel. To gain a true competitive edge, many firms turn to platforms like DrugPatentWatch. These services don’t just aggregate data; they curate, analyze, and contextualize it. For a 505(b)(2) strategist, the benefits are immense:

- Integrated Data: They collate information from the FDA, USPTO, international patent offices, clinical trial registries, and court records into a single, searchable interface. This saves hundreds of hours of manual data collection.

- Advanced Analytics: Platforms like DrugPatentWatch provide sophisticated analysis, such as projecting patent expiration landscapes, tracking litigation outcomes, and identifying all potential competitors (both ANDA and 505(b)(2)) for a given RLD.

- Alerts and Monitoring: You can set up alerts to be notified of critical events in real-time: a new patent is listed, a lawsuit is filed, a patent’s status changes at the PTAB, or a competitor files an application. This proactive monitoring allows you to adapt your strategy on the fly.

- Strategic Visualization: They often present complex data in intuitive formats, like timelines and charts, making it easier to identify patent cliffs and strategic gaps.

Using such a service is akin to having a dedicated team of analysts working for you 24/7. It allows your internal team to focus less on data gathering and more on what truly matters: high-level strategic decision-making.

Assembling the Puzzle: What to Look for in a Patent

Once you have access to the data, you need to know what you’re looking for. A patent is a complex legal document, but for a 505(b)(2) strategist, the focus is on a few key elements that dictate your freedom to operate.

Expiration Dates, Patent Types, and Term Extensions

This is the most basic, yet most fundamental, piece of information. The patent’s base term is 20 years from its earliest non-provisional filing date. However, this is rarely the final expiration date. You must account for:

- Patent Term Adjustment (PTA): The USPTO may add time to a patent’s term to compensate for administrative delays during its examination. This can add days, months, or even years.

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): An innovator can apply to have the term of one patent restored to compensate for the time lost during the FDA’s regulatory review process. This can add up to five years to a patent’s life, but the total effective patent life cannot exceed 14 years from the drug’s approval date [5].

- Pediatric Exclusivity: If the innovator conducts pediatric studies requested by the FDA, they are granted an additional six months of market exclusivity, which attaches to all existing patents and regulatory exclusivities for that drug.

A single drug can have a dozen patents, each with a different expiration date after all adjustments and extensions are calculated. Mapping these dates on a timeline is the first step in building your strategic plan.

Use Codes, Polymorphs, and Formulation Patents

Beyond the date, the type of patent is paramount.

- Composition of Matter Patent: This is typically the strongest type of patent. It covers the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) itself. It is virtually impossible to design around and usually represents the longest and most formidable barrier to entry.

- Method-of-Use Patent: This patent covers a specific approved use or indication of the drug. If the RLD is approved for three indications but only one is patented, you may be able to launch your 505(b)(2) product for the other two unpatented indications. This is the basis of the “skinny label” strategy.

- Polymorph Patent: Drugs can often exist in different solid-state crystalline forms, known as polymorphs. An innovator may have an early patent on the API and later patents on more stable or more soluble polymorphs. A 505(b)(2) strategy could involve developing a product with a different, non-infringing polymorph.

- Formulation Patent: This covers the specific recipe of the drug product—the API plus all the excipients (inactive ingredients). It is often possible to design a new formulation that avoids infringing the innovator’s patent claims, making this a fertile area for 505(b)(2) development.

Understanding this hierarchy is critical. A landscape dominated by a single, broad composition of matter patent presents a very different strategic challenge than one cluttered with multiple, narrow formulation and method-of-use patents.

The Strategic Chessboard: Identifying Optimal Filing Windows

With your intelligence arsenal assembled, it’s time to play the game. The goal is to identify the optimal window to file your 505(b)(2) NDA. This is not a single date but a strategic period defined by the interplay of patent expirations, litigation risk, and your own development timeline.

The Foundational Step: Mapping the RLD’s Patent Landscape

The first and most important task is to create a comprehensive visual map of the RLD’s entire patent and exclusivity portfolio. This is your master blueprint.

Creating a Comprehensive Patent Expiry Timeline

Start by listing every Orange Book-listed patent for the RLD. For each patent, find its adjusted and extended expiration date. Then, go to the USPTO and search for any other patents or applications owned by the innovator that are related to the drug but not listed in the Orange Book. Plot all of these dates on a single timeline.

Next, overlay the regulatory exclusivities. Mark the end of the 5-year NCE exclusivity (if applicable), any 3-year NCI exclusivities tied to new clinical studies, the 7-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE), and the 6-month pediatric exclusivity period.

The resulting timeline will reveal several critical features:

- The “Patent Cliff”: The date when the most significant patents (usually the composition of matter and primary formulation patents) expire.

- Patent Thickets: Clusters of overlapping patents with different expiration dates, designed to create uncertainty and deter competition.

- Strategic Gaps: Periods where only weaker patents (e.g., a specific method of use) remain, potentially creating an opening.

Identifying the “Pivotal Patent” – The Last Substantive Barrier

Within this timeline, your task is to identify the “pivotal patent.” This isn’t always the last patent to expire. It is the last patent that you believe is both valid and infringed by your proposed 505(b)(2) product. In other words, it’s the last patent that you cannot design around or confidently challenge.

Your entire timing strategy will revolve around this date. Your goal is to receive final FDA approval as close as possible to the expiration of this pivotal patent. This requires working backward from that date, factoring in the FDA review time (typically 10 months for a priority review, 12+ for standard), your development and manufacturing timeline, and, most importantly, the potential for patent litigation.

The Paragraph IV Certification: A High-Risk, High-Reward Gambit

What if you don’t want to wait for the pivotal patent to expire? What if your analysis suggests that a listed patent is invalid, unenforceable, or would not be infringed by your product? This is where you deploy the most aggressive and potent tool in the Hatch-Waxman arsenal: the Paragraph IV (P-IV) certification.

When you submit your 505(b)(2) NDA, you must make a certification for each patent listed in the Orange Book for the RLD. There are four options:

- Paragraph I: Patent information has not been filed.

- Paragraph II: The patent has expired.

- Paragraph III: The date on which the patent will expire. You commit to not launching until this date.

- Paragraph IV: The patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of your proposed drug product [6].

Filing a P-IV certification is an act of commercial warfare. You are directly challenging the innovator’s intellectual property. This act requires you to send a detailed notice letter to the patent holder explaining the basis for your challenge. The patent holder then has 45 days to decide whether to sue you for patent infringement.

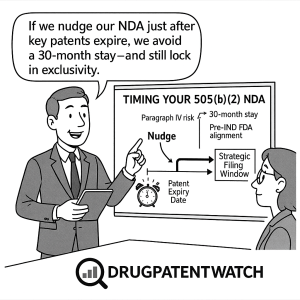

Understanding the 30-Month Stay of Approval

If the patent holder sues you within that 45-day window, it triggers an automatic 30-month stay of the FDA’s ability to grant final approval to your application. The FDA can still review your application and grant tentative approval, but final approval is frozen for up to 30 months, or until the patent litigation is resolved in your favor, whichever comes first.

This 30-month stay is the innovator’s primary defensive weapon. It buys them time to protect their market. For the 505(b)(2) filer, it’s a critical variable in the timing equation. Your decision to file a P-IV certification must be based on a cold, hard calculation:

- Can you win the ensuing litigation?

- Can you win it in less than 30 months?

- Does the commercial reward of launching early justify the enormous legal costs and the risk of the stay?

As one seasoned IP lawyer commented, “Filing a Paragraph IV is like placing a massive bet at the poker table. You need to be confident in your hand—your non-infringement or invalidity arguments—and you need the financial stamina to see the bet through, because your opponent is almost certainly going to call.”

Assessing the Likelihood of Litigation

Not all P-IV certifications result in a lawsuit. Before filing, you must assess the RLD holder’s propensity to litigate. Factors to consider include:

- Commercial Value of the RLD: The more revenue the brand drug generates, the more fiercely the innovator will defend it.

- Past Behavior: Has the company aggressively litigated its patents against other challengers? A review of past court cases is essential.

- Strength of the Patent: Is the patent a core composition of matter patent that has survived previous challenges, or is it a weaker, later-filed formulation patent with a dubious prosecution history?

- Your Company’s Reputation: Large, well-funded companies may be more willing to litigate than smaller firms.

This assessment is part art, part science. It requires deep legal expertise and a solid understanding of your adversary’s business strategy.

Finding the “White Space”: Opportunities for Non-Infringing Innovation

A P-IV challenge is not the only path. Often, a more elegant and less contentious strategy is to find the “white space” in the patent landscape—the areas left unprotected by the innovator’s patents. This is the essence of “designing around.”

Designing Around Existing Patents

This is where the detailed analysis of patent claims pays dividends. Once you understand exactly what the innovator’s patents protect, you can task your R&D team with designing a product that sidesteps those claims.

- Formulation Design-Around: If the RLD is protected by a patent on a specific controlled-release formulation using certain polymers, can you develop a new controlled-release mechanism using different, unpatented polymers?

- Polymorph Design-Around: If the innovator has patented Form I of their drug substance, can your chemists develop and stabilize a novel Form II that is not covered by the patent and possesses suitable characteristics for a drug product?

- Excipient Design-Around: Sometimes a patent’s claims are surprisingly narrow, covering a formulation with a specific, non-essential excipient. Simply swapping that excipient for another can be enough to achieve non-infringement.

This approach requires a tight, iterative collaboration between your patent attorneys and your formulation scientists. The lawyers identify the boundaries of the patent claims, and the scientists work creatively within those boundaries. This can lead to a Paragraph IV certification of non-infringement, which is often easier to defend than a certification of invalidity.

The “Skinny Label” Strategy: Carving Out Patented Indications

One of the most powerful “design-around” strategies is the skinny label. This applies when the RLD is approved for multiple indications, and only some of them are covered by method-of-use patents.

In this scenario, you can file a 505(b)(2) application seeking approval for only the unpatented indications. Your proposed product label will “carve out” or omit the patented uses. Because your product is not indicated for the patented use, you can certify that you do not infringe that patent.

This strategy allows you to get to market while the method-of-use patent is still in force, targeting a specific slice of the patient population. It’s a surgical approach that can be highly effective, although it has come under increased legal scrutiny in recent years, making expert legal guidance more critical than ever [7].

Advanced Timing Strategies: Integrating Regulatory and Commercial Factors

Masterful timing isn’t just about patents. It’s about orchestrating a symphony of patent strategy, regulatory exclusivity, and commercial intelligence. The most successful 505(b)(2) applicants see the chessboard in three dimensions.

Aligning with Regulatory Exclusivities

Regulatory exclusivities are non-patent-based periods of market protection granted by the FDA. They can be just as formidable as patents, and your timing strategy must account for them.

New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity

An NCE—a drug with an active moiety that has never been approved before—is granted five years of market exclusivity. During this period, the FDA cannot accept a 505(b)(2) or ANDA application for the first four years (the “NCE-1” date). This means the earliest you can submit your application is four years after the NCE’s approval, with the intention of launching at the five-year mark, assuming there are no blocking patents. Your entire development timeline must be reverse-engineered from this NCE-1 date.

New Clinical Investigation (NCI) Exclusivity

If an RLD holder conducts new clinical trials to support a significant change (like a new indication or a switch to OTC), they can be granted three years of NCI exclusivity. This exclusivity protects the change itself. The FDA cannot approve a 505(b)(2) or ANDA for that specific change for three years. Your strategy must either wait for this exclusivity to expire or focus on a different modification that is not covered by the NCI exclusivity. Importantly, a well-designed 505(b)(2) application can earn its own three-year exclusivity, creating a valuable barrier against subsequent filers.

Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) and Pediatric Exclusivity

Drugs for rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.) can receive seven years of Orphan Drug Exclusivity. This blocks the approval of any other drug for the same indication. Your timing must respect this long period of protection.

As mentioned earlier, the six-month pediatric exclusivity attaches to all existing patent and regulatory exclusivities. It is a critical date to factor into your timeline, as it pushes back the entire patent cliff by half a year. For a blockbuster drug, that six months can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars in sales for the innovator, making it a key milestone for you to track.

The Commercial Calculus: Market Dynamics and Competitive Intelligence

The third dimension of your timing strategy is a keen awareness of the commercial landscape. Patents and regulations don’t exist in a vacuum.

Analyzing the RLD Holder’s Lifecycle Management Strategy

Innovator companies are not passive. They actively manage their product’s lifecycle to maximize its revenue stream. This often involves filing for new indications, developing next-generation formulations (e.g., a daily pill to a weekly injection), and strategically listing new patents to create a “patent thicket.”

Your patent intelligence must include monitoring the RLD holder’s clinical trial activity and patent filings. Are they about to launch a new version of their own drug? If so, your 505(b)(2) product might end up competing not with the original RLD, but with a new-and-improved version. This could change your commercial forecast and even your choice of what kind of differentiated product to develop. Timing your entry to come after the original RLD loses patent protection but before the innovator can successfully switch the market to their next-generation product is a sophisticated strategic goal.

Monitoring Competitor 505(b)(2) and ANDA Filings

You are not the only one looking to enter the market. Other companies—both generic ANDA filers and other 505(b)(2) developers—are conducting the same analysis you are. Knowing who your potential competitors are and when they might file is crucial.

- ANDA Filers: The first company to file a “substantially complete” ANDA with a P-IV certification is eligible for 180 days of generic marketing exclusivity. During this time, no other ANDA can be approved. While this doesn’t block a 505(b)(2) approval, the launch of the first generic will dramatically impact pricing. Your optimal timing might be to launch before this first generic hits the market.

- Other 505(b)(2) Filers: Another 505(b)(2) applicant could be developing a product similar to yours. If they get their application approved first and earn three-year NCI exclusivity for their change, they could block your product’s approval. Monitoring competitor pipelines, clinical trials, and press releases is essential. Services that track this competitive landscape, like DrugPatentWatch, are invaluable here, providing early warnings about who else is in the race.

Your filing date is therefore not just a race against the RLD’s patents; it’s a race against your direct competitors.

Case Studies: Learning from Successes and Failures

Theory and strategy are best understood through real-world application. The history of the 505(b)(2) pathway is rich with examples of masterful timing, clever design-arounds, and costly miscalculations.

Case Study 1: The Masterful Reformulation (Suboxone® Film)

A quintessential 505(b)(2) success story is the lifecycle management of Suboxone® (buprenorphine and naloxone), a treatment for opioid dependence. The original product, approved in 2002, was a sublingual tablet. As the primary patents on the tablet formulation neared expiration, the innovator, Reckitt Benckiser, faced the prospect of a devastating patent cliff and generic competition.

The Strategy: The company developed a new dosage form: a sublingual film. They filed a 505(b)(2) application for this new film, relying on the safety and efficacy data from the original tablet. The film offered potential benefits like faster dissolution and individual packaging that could deter misuse.

The Timing and Execution:

- They launched the film well before the tablet patents expired, giving them time to convert patients and physicians from the old product to the new one.

- The new film was protected by its own set of patents and potentially its own market exclusivity.

- When generic versions of the tablet finally launched, a significant portion of the market had already been “product hopped” to the patent-protected film, preserving a large chunk of the brand’s revenue stream.

This was a textbook execution of a defensive 505(b)(2) strategy, perfectly timed to preempt generic erosion.

Case Study 2: The Audacious Paragraph IV Challenge (Treanda®)

Cephalon’s Treanda® (bendamustine) for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma provides an example of how a 505(b)(2) applicant can use a P-IV strategy to create a blockbuster. The active ingredient, bendamustine, was an old German drug. Cephalon developed a novel formulation and filed a 505(b)(2) application.

The Strategy: A key barrier was a series of patents held by a competitor covering specific methods of using bendamustine. Instead of waiting for these patents to expire, Cephalon filed a P-IV certification, challenging their validity.

The Timing and Execution:

- The P-IV filing triggered the expected lawsuit and 30-month stay.

- Cephalon prevailed in the litigation, with the courts finding the competitor’s patents invalid.

- This victory cleared the path for Treanda’s approval and launch. Because it was an orphan drug, it received 7-year ODE. The new formulation and clinical work also earned it 3-year NCI exclusivity.

- The successful P-IV challenge, combined with multiple layers of regulatory exclusivity, allowed Treanda to become a highly successful product, generating billions in sales.

This case demonstrates the high-reward nature of a well-executed P-IV strategy, turning a potential barrier into a market-clearing victory.

Case Study 3: A Timing Miscalculation and its Consequences

Hypothetical cases can be just as instructive. Consider a company, “PharmaCo X,” developing a new extended-release (ER) version of a blockbuster immediate-release (IR) drug for hypertension.

The Flawed Strategy:

- PharmaCo X correctly identifies a key formulation patent on the IR product that will expire on June 1, 2026. They plan their 505(b)(2) filing to get approval right after this date.

- They focus solely on the Orange Book and fail to do a deep dive into the USPTO database. They miss a pending patent application from the innovator covering the use of the drug in a specific patient subgroup with renal impairment—a subgroup that makes up 30% of the market.

- The innovator’s patent issues after PharmaCo X has already locked its clinical trial design and is halfway through its development program.

- Simultaneously, a competitor, “BioGen Y,” who used a more robust intelligence platform, was aware of this pending patent. BioGen Y designed their ER formulation specifically for patients without renal impairment and filed their 505(b)(2) with a skinny label, carving out the newly patented use.

The Consequence: PharmaCo X is now faced with a terrible choice: delay their program to redesign their trials, or launch and risk an infringement suit on the new patent. BioGen Y, through superior patent intelligence and timing, gets to market first with a de-risked product, capturing the initial wave of post-patent-cliff prescribing. PharmaCo X’s timing miscalculation, born from incomplete data, has put them years behind and at a significant competitive disadvantage.

Practical Execution: From Data to Dossier

Strategy without execution is merely a hallucination. Turning your brilliant timing plan into a successful NDA submission requires discipline, collaboration, and a dynamic approach.

Building a Cross-Functional Team: IP, Regulatory, and Commercial

Optimal 505(b)(2) timing is not the sole responsibility of the patent attorneys. It requires a deeply integrated, cross-functional team where information flows freely and decisions are made collaboratively.

- IP/Legal Team: Responsible for patent analysis, freedom-to-operate opinions, litigation risk assessment, and drafting the patent certification strategy.

- Regulatory Affairs Team: Responsible for FDA interactions, understanding the nuances of exclusivity rules, managing the submission timeline, and ensuring the NDA dossier is flawless.

- R&D/Formulation Team: Responsible for the scientific work of designing the product, conducting bridging studies, and executing any “design-around” strategies.

- Commercial/Business Development Team: Responsible for market analysis, competitive intelligence, forecasting, and ensuring the final product profile aligns with a viable commercial opportunity.

This team should meet regularly from the earliest stages of project consideration. A decision made in one department has immediate ripple effects on the others. If R&D proposes a formulation change, IP must immediately assess its patent implications. If the commercial team identifies a new competitive threat, the regulatory and IP teams must re-evaluate the filing timeline.

Developing a Dynamic Timing Model

Your initial patent expiry timeline is not a static document. It’s a living model that must be continuously updated with new information. This dynamic model should be a central tool for the cross-functional team.

It should track:

- Changes in patent status (new patents listed, patents invalidated in PTAB, litigation outcomes).

- Updates to competitor pipelines.

- Shifts in the innovator’s lifecycle management strategy.

- Your own internal development progress and any unexpected delays.

This model allows you to run “what-if” scenarios. What if the 30-month stay is triggered? How does that impact our launch date and budget? What if a competitor gets 180-day exclusivity? How does that change our first-year sales forecast? A dynamic model allows you to be agile, adapting your strategy as the battlefield changes.

The Pre-IND Meeting: Getting Early FDA Feedback

One of the most valuable tools for de-risking your timeline is the Pre-Investigational New Drug (Pre-IND) meeting with the FDA. This is an opportunity to get the agency’s early feedback on your proposed development plan.

You can discuss your proposed RLD, the bridging studies you believe are necessary, and your overall regulatory strategy. Positive feedback from the FDA can give you the confidence to proceed with your plan, while critical feedback can help you pivot early, saving you from wasting years and millions of dollars on a flawed development path. The outcome of this meeting is a critical input into your overall project timeline and, by extension, your NDA filing date.

The Future of 505(b)(2) Strategy: An Evolving Landscape

The world of pharmaceutical patents and regulation is never static. The strategies that work today must evolve to meet the challenges of tomorrow. Several trends are shaping the future of 505(b)(2) timing.

The Impact of AI and Machine Learning on Patent Analysis

The sheer volume of patent and scientific data is exploding. Manually sifting through thousands of patents and clinical trials is becoming untenable. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are poised to revolutionize patent intelligence.

AI-powered tools are emerging that can:

- Scan and analyze thousands of patents in minutes, identifying key concepts and potential infringement risks.

- Predict the likelihood of a patent being invalidated based on its characteristics and litigation history.

- Monitor global data sources for signals of competitive activity or new scientific breakthroughs.

Companies that embrace these technologies will be able to make faster, more accurate, and more predictive decisions about their 505(b)(2) candidates and timing strategies.

Evolving Legal Precedents and their Implications

The legal landscape surrounding Hatch-Waxman is constantly being shaped by court decisions. Rulings on issues like “skinny labels,” what constitutes “obviousness” for patent invalidity, and the scope of safe harbor for development activities can all have a profound impact on strategy.

For example, recent court decisions have created more uncertainty around the viability of the skinny label strategy, making the risk assessment for this approach more complex [7]. Staying abreast of these legal developments is not just a job for lawyers; it’s a strategic imperative for the entire development team. The optimal filing strategy must always be compliant with the latest interpretation of the law.

Conclusion: From Data Points to Decisive Action

The 505(b)(2) pathway is a testament to strategic ingenuity—a route that rewards not just scientific innovation, but business and legal acumen. At the heart of this acumen lies the ability to transform drug patent data from a collection of daunting legal documents and dates into a clear, actionable strategic plan.

Mastering this discipline requires moving beyond a superficial glance at the Orange Book. It demands a commitment to deep intelligence gathering, using every tool at your disposal—from the depths of the USPTO’s records to the sophisticated analytical power of platforms like DrugPatentWatch. It requires building a comprehensive map of the patent and exclusivity landscape, identifying the pivotal barriers, and understanding the high-stakes game of the Paragraph IV certification.

But most of all, it requires a holistic, integrated mindset. An optimal filing time is not a single point on a calendar; it is the convergence of patent timelines, regulatory exclusivities, commercial dynamics, and competitive pressures. It is the moment when legal risk is minimized and market opportunity is maximized.

By embracing a proactive, data-driven, and cross-functional approach, you can navigate the complexities of the 505(b)(2) chessboard with confidence and precision. You can turn the art of the nudge into a science, timing your market entry not by chance, but by design, and securing your product’s place as a commercial success.

Key Takeaways

- The 505(b)(2) pathway is a strategic tool for bringing differentiated products to market with reduced risk and cost by leveraging the FDA’s findings on a previously approved drug (RLD).

- Timing is paramount. The commercial success of a 505(b)(2) product is critically dependent on the timing of its NDA filing and subsequent market entry relative to the RLD’s patent and exclusivity landscape.

- Go beyond the Orange Book. A robust patent intelligence strategy involves a deep dive into USPTO databases, international records, and litigation history. Specialized platforms like DrugPatentWatch are crucial for aggregating and analyzing this complex data efficiently.

- Map the entire landscape. Create a comprehensive timeline of all relevant patents (with all term adjustments/extensions) and regulatory exclusivities to identify the true “patent cliff” and the pivotal patent that represents your main barrier.

- The Paragraph IV certification is a high-risk, high-reward strategy. It can enable early market entry but almost always triggers costly litigation and a 30-month stay of approval. The decision to file a P-IV must be based on a rigorous assessment of the patent’s weakness and the innovator’s propensity to litigate.

- “Design-arounds” and “skinny labels” are powerful, lower-risk strategies. Finding the “white space” by creating non-infringing formulations or carving out patented indications can provide a faster and less contentious path to market.

- Integrate all intelligence. Optimal timing requires a three-dimensional view that combines patent data, regulatory exclusivity rules, and commercial intelligence (innovator lifecycle management and competitor activity).

- Execution requires a cross-functional team. Tight collaboration between IP, regulatory, R&D, and commercial teams is non-negotiable for developing and executing a dynamic and adaptive timing strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How has the FDA’s requirement to list the patent submission date in the Orange Book affected timing strategy?

The requirement, part of the 2020 Orange Book modernization rules, adds another layer to strategic analysis. The submission date of the patent (to the FDA for listing, not the USPTO filing date) can be important in certain disputes, particularly regarding the timing of notice letters and the eligibility for 180-day exclusivity. For a 505(b)(2) strategist, it provides more transparency and another data point to verify. It helps ensure that an innovator isn’t improperly listing a patent late to deliberately disrupt a competitor’s pending application. While not a revolutionary change, it reinforces the need for meticulous data tracking and verification in any filing timeline.

2. What is the single biggest mistake companies make when analyzing patent data for a 505(b)(2) filing?

The most common and costly mistake is “claim myopia”—that is, focusing only on the patent expiration date without conducting a thorough analysis of the patent’s claims. A patent expiring in 2035 sounds intimidating, but if its claims are extremely narrow and cover, for example, a formulation containing a specific, non-essential sugar, it may be easily designed around. Conversely, a patent expiring sooner might contain broad, unassailable claims on the active molecule itself. Failing to understand the scope and strength of the claims leads to flawed “go/no-go” decisions, wasted R&D resources, and catastrophic miscalculations in litigation risk.

3. Can a 505(b)(2) application itself receive its own period of market exclusivity?

Yes, and this is a crucial part of its value proposition. A 505(b)(2) application is not eligible for the 5-year NCE exclusivity, but if the application required new, essential clinical investigations to be approved, it can be granted its own 3-year period of NCI (New Clinical Investigation) exclusivity. This exclusivity prevents the FDA from approving a subsequent 505(b)(2) or ANDA that relies on the 505(b)(2) holder’s protected change for three years. It can also be eligible for 7-year Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE) and 6-month pediatric exclusivity, creating a valuable protective moat for the newly approved product.

4. How does international patent data factor into a U.S. 505(b)(2) filing strategy?

International patent data provides critical strategic context. By analyzing the “patent family” of a U.S. patent—its counterparts filed in Europe, Japan, Canada, etc.—you can gain significant insights. For example, if a U.S. patent’s claims were narrowed significantly during examination in the stringent European Patent Office (EPO), it might reveal prior art or arguments that can be used to challenge the validity of the U.S. patent. Furthermore, tracking the innovator’s global patenting strategy can signal their future intentions for lifecycle management long before those plans are evident in the U.S. alone.

5. With the rise of biologics, is there an equivalent timing strategy for biosimilars under the BPCIA?

Yes, there is a parallel universe of strategic timing for biosimilars, governed by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). The principles are similar, but the mechanics are unique. Instead of the Orange Book, there is the “Purple Book.” Instead of the straightforward 30-month stay, there is the complex and highly choreographed “patent dance,” a series of information exchanges and litigation phases between the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor [8]. The goal is the same—to analyze a complex patent portfolio and time market entry—but the specific rules of engagement, timelines, and types of patents (which often cover manufacturing processes and cell lines) are distinct to the world of biologics.

References

[1] Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Section 505(b)(2). 21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(2).

[2] DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2016). Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs. Journal of Health Economics, 47, 20–33.

[3] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025). Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (The Orange Book). Retrieved from fda.gov.

[4] LaMattina, J. (2011). The impact of mergers on pharmaceutical R&D. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 10, 559–560.

[5] U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. (n.d.). Patent Term and Patent Term Extension. Retrieved from uspto.gov.

[6] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2017). Guidance for Industry: Applications Covered by Section 505(b)(2).

[7] Noonan, K. E. (2021). GlaxoSmithKline v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021). Patent Docs. Retrieved from https://www.patentdocs.org/2021/10/glaxosmithkline-v-teva-pharmaceuticals-usa-inc-fed-cir-2021-1.html.

[8] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Biosimilar Development, Review, and Approval. Retrieved from fda.gov.