Introduction: The Unsung Heroes of Healthcare

In modern medicine blockbuster brand-name drugs often take center stage, celebrated for their innovative breakthroughs and life-altering potential. They are the stars of the show, backed by billions in research and development and heralded by massive marketing campaigns. But behind the curtain, working tirelessly to make healthcare sustainable, accessible, and equitable, are the unsung heroes: generic drugs.

These are not mere copies; they are the backbone of a functioning healthcare system, the workhorses that ensure the revolutionary treatments of yesterday become the affordable standards of today. Every time a patient fills a prescription for a fraction of the cost of its branded counterpart, they are experiencing the direct benefit of a complex, high-stakes, and fascinating journey—the generic drug development process.

The Generic Revolution: More Than Just a Cheaper Pill

The impact of generic drugs is staggering. In the United States alone, they account for over 90% of all prescriptions filled, yet they represent just under 20% of total prescription drug spending. This incredible efficiency frees up trillions of dollars within the healthcare system, money that can be reinvested into new research, hospital infrastructure, and patient care. Think of it as a perpetual innovation fund, where the success of past inventions directly fuels the discoveries of the future.

But the story of generics isn’t just about economics. It’s about access. It’s about the diabetic patient who can afford their daily metformin, the individual with high blood pressure who has consistent access to lisinopril, and the cancer patient whose treatment regimen is made possible by affordable supportive care drugs. This is the profound human impact of the generic industry—a story of science, strategy, and regulation converging to serve a fundamental public good.

Setting the Stage: Why Understanding This Process is a Strategic Imperative

For professionals in the pharmaceutical, investment, and healthcare sectors, understanding the generic drug development process is not an academic exercise; it’s a strategic imperative. The journey from identifying a potential candidate to launching a successful generic product is a high-stakes chess match played out over years. It demands a sophisticated understanding of patent law, regulatory science, chemistry, manufacturing, and market dynamics.

Why does it matter so much? Because fortunes are made and lost in the details. A six-month delay in an ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) approval can mean losing out on the lucrative 180-day exclusivity period. A miscalculation in API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) sourcing can cripple a launch. A poorly designed bioequivalence study can send a development team back to the drawing board for years.

This guide is designed for you—the business leader, the regulatory affairs specialist, the R&D scientist, the portfolio manager, the investor. We will move beyond the textbook definitions to provide a comprehensive, strategic look at the entire lifecycle, from the initial spark of an idea to the final push into the market. We’ll explore the critical decision points, the hidden pitfalls, and the emerging opportunities that define this dynamic industry.

A Roadmap for the Journey Ahead

Our journey will be structured in stages, mirroring the real-world process:

- The Foundation: We’ll begin with the legal and economic landscape, exploring the Hatch-Waxman Act, the patent cliff, and the strategic importance of market exclusivities.

- Strategic Blueprint: We’ll dive into the crucial pre-development phase, where candidate selection, patent analysis, and API sourcing set the stage for success or failure.

- Laboratory Crucible: Next, we’ll enter the lab to understand the science of reverse engineering, formulation, and analytical development.

- The Human Element: We’ll examine the linchpin of generic approval—the bioequivalence study—and explore the unique challenges posed by complex generics.

- The Regulatory Marathon: This section will demystify the ANDA, breaking down the submission process, the FDA review cycle, and how to navigate agency feedback.

- The Final Mile: Finally, we’ll cover the critical steps of pre-approval inspections and the strategic planning required for a successful commercial launch.

Throughout this exploration, we will weave in expert insights, real-world examples, and actionable strategies to help you not just understand the process, but master it. So, let’s begin our journey from molecule to market.

The Foundation: Patents, Exclusivity, and the Hatch-Waxman Act

Before a single beaker is filled or a single tablet is pressed, the generic drug development process begins in the realm of law and economics. The entire industry exists within a carefully constructed framework designed to balance two competing interests: rewarding the innovation of brand-name drug companies and promoting affordable access to medicines for the public. Understanding this foundation isn’t just important; it’s the price of admission.

The Patent Cliff: A Precipice of Opportunity

Imagine a blockbuster drug, one that generates billions in annual revenue for its innovator company. This revenue is protected by a fortress of patents covering its active molecule, its formulation, its method of use, and more. For a period, typically around 20 years from the initial patent filing, the innovator enjoys a monopoly. But patents, like all good things, must come to an end.

The “patent cliff” is the term used to describe the period when a drug’s key patents expire, exposing it to generic competition. For the brand company, it can be a terrifying drop in revenue, often losing 80-90% of their market share within a year. But for a generic company, this cliff is not a precipice of doom; it’s a vista of pure opportunity. It’s the starting gun for a race to the market.

Defining the Patent Cliff and Its Market Impact

The patent cliff is a predictable, recurring event in the pharmaceutical lifecycle. It’s the moment the market shifts from a monopoly to a competitive environment. The first generic to launch, especially if it has 180-day exclusivity, can capture a massive portion of the market overnight. Subsequent generics further drive down the price, culminating in a stable, low-cost market that delivers immense value to the healthcare system.

The scale of this impact is hard to overstate. When a drug like Lipitor (atorvastatin), which once earned Pfizer over $10 billion annually, went generic, the market was transformed. The potential reward for the first generic filers was enormous, but so was the pressure to get the science and regulatory strategy exactly right. Every major patent expiry creates a similar gold rush, attracting numerous generic players who have been preparing for years.

Using Data to Predict and Prepare: The Role of Services like DrugPatentWatch

You can’t win a race if you don’t know where the starting line is. For generic companies, the starting line is the patent expiry date. But it’s not as simple as looking up one date on a calendar. A single drug can be protected by a complex web of dozens of patents and multiple types of regulatory exclusivities. There are composition of matter patents, formulation patents, method-of-use patents, and process patents. Some may be challenged, some may be extended, and some may be irrelevant to a generic design.

This is where strategic intelligence becomes paramount. Navigating this “patent thicket” is a full-time job. How do you identify the most promising opportunities years in advance? How do you track litigation outcomes that could shift an expiry date? This is precisely the problem that services like DrugPatentWatch are built to solve. They provide comprehensive databases and analytics that allow companies to:

- Identify Blockbuster Expiries: Pinpoint which high-revenue drugs are losing patent protection and when.

- Analyze the Patent Estate: Dissect the entire collection of patents associated with a drug to understand which ones are the real barriers to entry.

- Track Litigation: Monitor Paragraph IV challenges and their outcomes, which can accelerate or delay generic entry.

- Assess the Competitive Landscape: See which other generic companies have already filed ANDAs, signaling how crowded the field might be.

Using this data, a portfolio manager can move from a reactive to a proactive stance, building a development pipeline that is diversified, commercially viable, and strategically timed. It’s about making multi-million-dollar decisions with the best possible information, turning the complexity of patent law from a barrier into a competitive advantage.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Magna Carta of Generic Drugs

If the patent cliff is the opportunity, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984—universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act—is the rulebook that makes the opportunity accessible. Before 1984, the path for generics was treacherous and unclear. A generic company had to conduct its own expensive and duplicative clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy, and it couldn’t even begin that work until after the brand patent expired, giving the innovator a significant head start.

Hatch-Waxman fundamentally changed the game, creating the modern generic industry as we know it.

Balancing Innovation and Accessibility

The genius of the Hatch-Waxman Act lies in its grand compromise. It sought to give something to both sides of the pharmaceutical aisle.

- For Innovator Companies: It offered a mechanism to restore some of the patent life that was lost during the lengthy FDA approval process for their new drug, effectively extending their monopoly period.

- For Generic Companies: It created a streamlined approval pathway, the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), that did not require repeating costly and unethical clinical trials.

This balance ensures that innovators are still incentivized to invest in risky R&D, while also creating a clear, predictable pathway for generics to enter the market as soon as patents permit.

Key Provisions: The ANDA Pathway and Patent Certifications

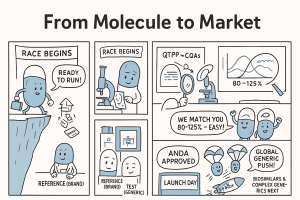

The ANDA is the heart of the Hatch-Waxman Act. Instead of new clinical trials, a generic company “abbreviates” its application by relying on the FDA’s previous finding that the innovator’s drug is safe and effective. The generic company’s burden of proof is different; it must demonstrate two key things:

- Pharmaceutical Equivalence: The generic has the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, and route of administration as the brand-name reference listed drug (RLD).

- Bioequivalence: The generic is absorbed into the bloodstream and becomes available at the site of action at the same rate and extent as the RLD.

Crucially, Hatch-Waxman also established a formal process for generic companies to address the brand’s patents. When submitting an ANDA, a generic manufacturer must make a certification for each patent listed in the FDA’s “Orange Book” for the RLD. There are four possible certifications:

- Paragraph I: The required patent information has not been filed.

- Paragraph II: The patent has already expired.

- Paragraph III: A certification that the generic will not be marketed until the patent expires on a specified date.

- Paragraph IV: A certification that the patent is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the proposed generic product.

The Paragraph IV certification is the most aggressive and consequential. It’s a direct challenge to the innovator’s intellectual property and often triggers immediate litigation.

Navigating the Maze of Exclusivities

Beyond patents, the FDA grants various types of “exclusivities,” which are periods of market protection that are separate from patents. They are granted upon approval of a drug and run concurrently with any patents. Understanding these is critical for timing a generic launch.

180-Day “First-to-File” Exclusivity: The Ultimate Prize

To incentivize generic companies to undertake the risk and expense of challenging patents, Hatch-Waxman created a powerful reward: 180-day exclusivity. This is granted to the first company (or companies) that submits a “substantially complete” ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification.

For 180 days, the FDA will not approve any subsequent ANDAs for the same drug. This means the first-to-file generic gets to compete only with the brand drug, not with a flood of other generics. This duopoly allows the first generic to price its product at a slight discount to the brand but still at a significant premium compared to a fully genericized market. This six-month window is often where the majority of the profit from a generic launch is made. It is, without a doubt, the most sought-after prize in the generic industry and the primary driver behind the “race to file.”

Other Exclusivities: Pediatric, Orphan Drug, and NCE

While 180-day exclusivity is specific to generics, innovators have their own set of valuable exclusivities that a generic strategist must track:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: A five-year period of data exclusivity for drugs containing an active ingredient never before approved by the FDA. No generic ANDA can even be submitted for the first four years of this period (the “NCE-1” date).

- Pediatric Exclusivity (PED): Provides an extra six months of market protection (added to existing patents and other exclusivities) as a reward for the brand company conducting studies in children. This can unexpectedly delay a generic launch by six months and must be factored into all timelines.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity (ODE): Grants seven years of market exclusivity for drugs that treat rare diseases (affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.).

A generic company’s timeline is therefore a complex calculation, factoring in the expiration of multiple patents, the potential for a pediatric extension, and the expiry of any data exclusivities. Missing one of these pieces can lead to a disastrous miscalculation of the launch date.

Stage 1: The Strategic Blueprint – Pre-Development and Candidate Selection

The most successful generic companies are not just brilliant scientists; they are master strategists. The war for market share is often won or lost years before the product launch, in the conference rooms where portfolio decisions are made. This pre-development stage is about asking the right questions, performing rigorous due diligence, and placing smart bets. It’s about building a blueprint for success.

The Art of the Portfolio: Choosing Your Battles Wisely

A generic company cannot pursue every drug coming off patent. Resources—financial, technical, and human—are finite. The goal is to build a balanced portfolio of products with varying levels of risk, cost, and potential reward. This selection process is a multi-faceted analysis.

Commercial Viability Analysis: Beyond the Patent Expiry Date

Simply knowing a drug’s patent expiry date and its brand sales is table stakes. A deep commercial analysis goes much further. Key questions include:

- Market Size and Dynamics: What are the current and projected sales of the brand product? Is the market growing or shrinking? Are there new, superior therapies emerging that could make this drug obsolete by the time the generic launches?

- Competitive Landscape: How many other generic companies are likely to file? Intelligence from sources like DrugPatentWatch can provide clues about who has already filed an ANDA. A market with one or two “first filers” is far more attractive than one with ten.

- Pricing and Reimbursement: What is the likely pricing scenario? If it’s a “first generic,” the price will be higher. If it’s the 10th generic, prices will plummet. Will pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and insurance companies readily reimburse the generic? Are there any complexities with rebates or formularies?

- Lifecycle Management: Is the brand company likely to launch its own “authorized generic” to compete with the first filer? Are they developing a next-generation “product-line extension” (e.g., a once-daily version of a twice-daily drug) that could cannibalize the market for the original?

A promising candidate is one with a large, stable market, a limited number of expected competitors, and a clear path to reimbursement.

Technical Feasibility: Can We Actually Make This?

A billion-dollar market opportunity is worthless if you can’t successfully develop the product. The technical assessment is a reality check performed by the R&D and manufacturing teams.

- API Complexity and Availability: Is the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) difficult to synthesize? Does it have complex polymorphic forms that are hard to control? Are there reliable, high-quality suppliers, or will we need to develop the API in-house at great expense?

- Formulation Challenges: Is the drug a simple immediate-release tablet, or is it a “complex generic”? Complex products like long-acting injectables, transdermal patches, inhalers, or drug-device combinations present significant scientific and regulatory hurdles. The question isn’t just “can we make it?” but “can we prove it’s bioequivalent?”

- Manufacturing Requirements: Does the product require specialized manufacturing technology or equipment that we don’t possess? For example, sterile manufacturing for injectables is far more complex and costly to set up than solid oral dosage form manufacturing.

A product might look great on paper commercially but be rejected because the technical risk is deemed too high for the potential reward.

The Regulatory Gauntlet: Assessing the Pathway to Approval

Finally, the regulatory affairs team weighs in. They assess the likely path to approval and identify potential roadblocks.

- Clarity of the BE Pathway: For most simple drugs, the FDA has clear guidance on how to conduct the required bioequivalence (BE) study. For complex generics, the guidance may be less clear or still in development, introducing significant uncertainty into the project timeline and cost.

- Potential for Citizen Petitions: Is the brand company likely to file a “Citizen Petition” with the FDA? This is a tactic sometimes used to delay generic approval by raising questions about the science or safety standards for generic versions. While often ultimately denied, these petitions can cause significant delays and require resources to rebut.

- Labeling Issues: Are there complexities with the product’s label? For example, if a brand drug is approved for three indications but one of them is still protected by a method-of-use patent, the generic company must create a “skinny label” that carves out the protected indication. This process can be complex and a source of litigation.

Only when a candidate has passed muster on all three fronts—commercial, technical, and regulatory—is it typically greenlit for development.

The Patent Dance: Intellectual Property Due Diligence

This is where the legal and scientific teams collaborate in a high-stakes “patent dance.” The goal is to find a path to market that doesn’t infringe the innovator’s valid intellectual property.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Avoiding the Lawsuit Landmines

A Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) analysis is a comprehensive review of the “patent thicket” surrounding the brand drug. Patent attorneys and scientists work together to answer a critical question: “Can we launch our proposed product without being successfully sued for patent infringement?”

This involves:

- Identifying all relevant patents: Not just the ones listed in the Orange Book, but any other patents that could potentially cover the formulation, manufacturing process, or use of the drug.

- Analyzing the patent claims: The “claims” are the legally operative part of a patent that define the boundaries of the invention. The team must determine if their proposed generic product falls within those boundaries.

- Assessing patent validity: Even if the product seems to infringe, the team might conclude that the patent itself is invalid (e.g., it wasn’t truly novel or was obvious at the time of filing).

The outcome of the FTO analysis dictates the development strategy. It might lead to a decision to “design around” a patent by, for example, using different non-active ingredients (excipients) than the brand to avoid a formulation patent.

Paragraph IV Certifications: The High-Risk, High-Reward Strategy

If the FTO analysis concludes that a key patent is invalid or not infringed, the company can choose the aggressive path of a Paragraph IV certification. This is a declaration to the FDA and the brand company that you believe you have a right to come to market before the patent expires.

Filing a Paragraph IV certification almost guarantees two things:

- A Lawsuit: The Hatch-Waxman Act gives the brand company 45 days to sue the ANDA filer for patent infringement.

- A 30-Month Stay: If a lawsuit is filed, the FDA is automatically barred from giving final approval to the ANDA for up to 30 months (or until the court case is resolved, whichever comes first).

This 30-month stay is a critical period. It gives the parties time to litigate the patent dispute. The generic company might win the case, lose the case, or, very commonly, reach a settlement agreement with the brand company that allows for a generic launch on a specific date, often before the patent’s full expiration. Pursuing a Paragraph IV strategy is expensive and risky, but it is the only path to securing the coveted 180-day exclusivity.

Sourcing the Spark: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) Strategy

The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient is the therapeutic heart of any drug. A solid API strategy is a cornerstone of a successful generic program. An unreliable API supply can delay development, halt production, and even lead to a product recall.

Make vs. Buy: Strategic Sourcing Decisions

The first major decision is whether to synthesize the API in-house or source it from a third-party manufacturer.

- Making (Vertical Integration): Developing and manufacturing the API in-house provides maximum control over quality, supply, and cost. It also protects proprietary knowledge about the synthesis process. However, it requires massive capital investment in specialized facilities and scientific expertise. It’s a long-term strategic bet.

- Buying (Outsourcing): Sourcing API from external suppliers is more common, especially for smaller companies. It’s more capital-efficient and allows the company to leverage the expertise of specialized API manufacturers. The global API market is vast, with major hubs in India and China.

The “buy” decision is not simple. It involves a trade-off between cost, quality, and supply chain security. Many companies opt for a hybrid approach, qualifying at least two different suppliers from different geographic regions to mitigate risk.

Qualifying API Suppliers: Quality, Cost, and Reliability

Choosing an API supplier is one of the most critical decisions in the development process. The supplier’s quality becomes your quality. The qualification process is intense and involves:

- Drug Master File (DMF) Review: The API supplier typically files a DMF with the FDA. This is a confidential document that details the chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) of the API. The generic company gets a Letter of Authorization (LOA) to allow the FDA to review the DMF in support of their ANDA. The generic company will review the “open” part of the DMF and scrutinize the supplier’s quality systems.

- Quality Audits: The generic company will conduct a rigorous on-site audit of the potential supplier’s manufacturing facility. They will inspect everything from raw material handling to process controls, quality control labs, and data integrity practices to ensure compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP).

- Sample Testing: The R&D team will obtain samples of the API from the potential supplier and run them through a battery of tests to confirm its identity, purity, physical characteristics (like particle size, which can affect formulation), and impurity profile. Any unexpected impurity could jeopardize the entire development program.

A company might evaluate five potential suppliers to select the two that offer the best balance of impeccable quality, a secure supply chain, and a competitive cost. This rigorous upfront work prevents catastrophic failures down the line.

Stage 2: The Laboratory Crucible – Pharmaceutical Development

With a strategic blueprint in hand, the project moves from the conference room to the laboratory. This is where science takes the lead. The goal is to create a product that is, for all intents and purposes, a therapeutic twin of the innovator’s drug. It’s a process of meticulous reverse engineering, innovative formulation, and rigorous analytical testing. This stage is governed by the philosophy of “Quality by Design” (QbD), a systematic approach that builds quality into the product from the very beginning.

Reverse Engineering the Innovator: Deformulation and Characterization

You can’t create a copy of something without first understanding it inside and out. The first step in the lab is to take the brand-name drug—the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)—and carefully take it apart. This process is known as deformulation.

Imagine being a chef tasked with recreating a rival’s secret sauce. You would taste it, smell it, analyze its texture, and use sophisticated techniques to identify every single ingredient, from the main tomatoes down to the faintest pinch of spice. Deformulation is the pharmaceutical equivalent.

What’s in the Box? Identifying Excipients and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

Using advanced analytical techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Mass Spectrometry (MS), and various forms of spectroscopy, scientists identify and quantify every component of the RLD:

- The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API): This is already known, but its physical properties (crystal form, particle size) in the final product are scrutinized.

- The Excipients: These are the inactive ingredients that form the delivery system for the API. They include fillers (to add bulk), binders (to hold the tablet together), disintegrants (to help it dissolve in the body), lubricants (to aid manufacturing), coatings, and colorants.

The goal is not just to identify the “what” but also the “how much.” The result is a recipe for the brand-name drug. But the analysis goes deeper. Scientists must also identify the Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) of the drug product. These are the physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological attributes that must be controlled to ensure the product has the desired quality. For a simple tablet, CQAs might include its hardness, thickness, dissolution rate, and content uniformity. For a more complex product, it could involve dozens of parameters.

The “QbD” Philosophy: Quality by Design in Generic Formulation

Historically, drug development often followed a “quality by testing” model. A batch was made, and then it was tested at the end to see if it met specifications. The modern approach, championed by the FDA, is Quality by Design (QbD).

QbD turns this on its head. It’s a proactive, systematic approach that begins with the end in mind. The process starts by defining a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP), which is a prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product that ideally will be achieved. It’s essentially a list of what the perfect generic drug will look like and how it will perform, based on the characterization of the RLD.

From the QTPP, the team identifies the CQAs. Then, they work backward to identify the Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) of the raw materials (both API and excipients) and the Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) of the manufacturing process that could affect those CQAs.

For example:

- QTPP: The tablet should dissolve in the stomach within 30 minutes.

- CQA: Dissolution rate at 30 minutes must be >85%.

- CMA: The particle size of the API and the type of disintegrant used.

- CPP: The compression force used to make the tablet and the speed of the tablet press.

By understanding these relationships, scientists can define a “design space”—a multi-dimensional combination of input variables (e.g., material attributes) and process parameters that has been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality. Working within this design space ensures that every batch produced will meet the quality target, making the process robust and reliable.

Industry Insight

<blockquote>”Implementing Quality by Design is not just a regulatory expectation; it’s a fundamental shift in mindset. It forces a deep understanding of the product and process, which ultimately reduces manufacturing failures, minimizes batch-to-batch variability, and accelerates development. A dollar spent on QbD upfront can save ten dollars in manufacturing problems or regulatory delays later on.”

– Former FDA Official, Office of Pharmaceutical Quality</blockquote>

Building a Better Copy: Formulation and Process Development

Armed with the RLD’s recipe and a QbD framework, the formulation scientists get to work. Their job is to create a new recipe for the generic product that is pharmaceutically equivalent to the brand but is also robust, scalable, and ideally, not infringing on any formulation patents.

Choosing the Right Excipients: The Supporting Cast

Generic companies will often try to use the same excipients as the brand, in roughly the same quantities. This is known as being “qualitatively (Q1) and quantitatively (Q2) the same.” A Q1/Q2 formulation often has a smoother regulatory path, as it reduces the number of variables that could affect performance.

However, sometimes a company must deviate. This could be for several reasons:

- Patent Avoidance: The brand may have a patent on a specific combination of excipients. The generic formulator must “design around” this by selecting alternative, non-infringing excipients that achieve the same function.

- Improved Manufacturability: A different binder might lead to better tablet hardness, or a different lubricant might allow the manufacturing press to run faster and more efficiently.

- Supplier Availability: The specific grade of an excipient used by the brand may no longer be available or may be prohibitively expensive.

Choosing new excipients is a careful balancing act. The formulator must ensure the new ingredient is compatible with the API and other excipients and does not negatively impact the drug’s stability or its performance in the body.

Process Optimization and Scale-Up: From Beaker to Batch

Developing a formulation in a lab that makes a few hundred tablets is one thing. Developing a process that can manufacture millions of tablets consistently is another entirely. This is the challenge of process optimization and scale-up.

Using the QbD framework, scientists conduct experiments to define the “design space.” They might use statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) to efficiently study the impact of different process parameters (like mixing time, granulation fluid amount, compression force, and drying temperature) on the product’s CQAs.

Once the process is well understood and optimized on a small, pilot scale, it must be scaled up to the size of a full commercial batch. This is a critical step. The physics of processes like mixing and drying can change dramatically when moving from a 1 kg batch to a 500 kg batch. The tech transfer team must demonstrate that the process remains under control and continues to produce a product that meets all quality attributes at the larger scale. This is confirmed by manufacturing several validation batches which are intensively tested to prove the process is robust and reproducible.

The Proof is in the Purity: Analytical Method Development and Validation

Running parallel to all formulation and process development is the work of the analytical chemistry department. Their role is to develop the tools to measure quality. If the formulation team is the chef, the analytical team provides the calibrated thermometers, scales, and taste buds. You cannot control what you cannot measure.

Ensuring Identity, Strength, Purity, and Quality (ISPQ)

The analytical team develops and validates a suite of tests to be performed on the raw materials, in-process materials, and the final drug product. These tests are designed to confirm:

- Identity: Is the drug what it says it is? Techniques like Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) are often used.

- Strength (Assay): Does the tablet contain the correct amount of API? This is typically measured with high precision using HPLC.

- Purity: Are there any impurities or degradation products present? If so, are they below the strict limits set by regulatory authorities (like the ICH – International Council for Harmonisation)? HPLC and Gas Chromatography (GC) are workhorse techniques here.

- Quality: Does the product meet its other quality attributes? This includes tests for dissolution (how quickly it dissolves), content uniformity (to ensure every tablet has the same dose), hardness, friability (resistance to breaking), and water content.

Each of these analytical methods must be rigorously validated. This means the lab must prove, through a series of experiments, that the method is accurate, precise, specific, sensitive, and robust. This validation package becomes a key part of the ANDA submission.

Stability Testing: Will It Stand the Test of Time?

A drug product is useless if it degrades on the pharmacy shelf before it reaches the patient. The stability testing program is designed to determine the product’s shelf-life and recommended storage conditions.

Validation batches of the drug product, packaged in the proposed commercial container (e.g., bottles, blister packs), are placed into controlled-environment stability chambers. These chambers maintain specific temperature and humidity conditions.

- Long-Term Conditions: Typically $25^\\circ C \\pm 2^\\circ C$ and 60 Relative Humidity (RH). Samples are pulled and tested at set intervals (e.g., 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36 months).

- Accelerated Conditions: Typically $40^\\circ C \\pm 2^\\circ C$ and 75 RH. Testing at these harsher conditions can help predict the long-term stability and detect potential degradation issues more quickly. Significant changes under accelerated conditions might signal a problem with the formulation or packaging.

The data gathered from this extensive program are used to establish the product’s expiration date. A minimum of six months of accelerated and long-term data on at least three primary batches is typically required for the initial ANDA submission. The study continues for years to confirm the assigned shelf life. This ensures that the generic drug remains safe and effective throughout its entire lifecycle.

Stage 3: The Human Element – Bioequivalence and Clinical Studies

After months or even years of meticulous lab work, the generic product is ready for its most important test: the human study. This is the moment of truth. All the reverse engineering, formulation science, and analytical testing have been leading to one pivotal question: does our drug perform the same way in the human body as the brand-name drug? This is the principle of bioequivalence, the scientific bedrock upon which the entire generic drug approval system is built.

The Core of the ANDA: Proving Bioequivalence (BE)

The Hatch-Waxman Act’s great innovation was freeing generic companies from the need to repeat large, expensive, and time-consuming clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy. That was already done by the innovator. The generic’s burden is to prove that its product is a suitable therapeutic alternative. It does this by demonstrating bioequivalence.

What is Bioequivalence? The Scientific Basis for Interchangeability

Bioequivalence does not mean the two drugs are identical in every way. They may have different inactive ingredients, different colors, or different shapes. Bioequivalence means that they deliver the same amount of the active ingredient to the bloodstream over the same period of time.

The assumption, which has been validated over decades of experience, is that if two products produce the same concentration-time profile in the blood, they will have the same therapeutic effect and the same safety profile at the site of action in the body. This is why a pharmacist can confidently substitute a generic for a brand.

The study to prove this is typically a randomized, single-dose, two-way crossover study involving a small number of healthy volunteers (often between 24 and 72 subjects). Here’s how it works:

- Randomization: The volunteer group is randomly split in two.

- Period 1: Group A receives the generic drug (the Test product, “T”), and Group B receives the brand-name drug (the Reference product, “R”). Blood samples are taken at regular intervals over a set period (e.g., 24-72 hours) to measure the concentration of the drug in the plasma.

- Washout Period: A sufficient amount of time passes for the drug to be completely eliminated from the subjects’ bodies.

- Period 2 (Crossover): The groups switch. Group A now receives the Reference drug (R), and Group B receives the Test drug (T). Blood samples are taken again in the same way.

The crossover design is powerful because each volunteer acts as their own control, which reduces the variability in the data caused by differences between individuals.

Designing the BE Study: Pharmacokinetic (PK) Endpoints (Cmax, Tmax, AUC)

From the blood concentration data collected for each subject, pharmacologists calculate several key pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters:

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration): This is the peak concentration the drug reaches in the bloodstream. It’s a measure of the rate of absorption.

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): This is the total area under the plasma concentration-time curve. It represents the extent of drug absorption—the total amount of drug the body is exposed to. There are two types: AUC_0−t (from time zero to the last measurable concentration) and AUC_0−infty (extrapolated to infinity).

- Tmax (Time to Maximum Concentration): The time at which Cmax is reached. It’s another indicator of the absorption rate. Tmax is noted but not typically subject to the same statistical analysis as Cmax and AUC.

The goal of the study is to prove that these key parameters for the generic product are statistically equivalent to those of the brand product.

The 90% Confidence Interval: The Statistical Hurdle

Equivalence is not determined by simply seeing if the average Cmax and AUC are the same. The FDA uses a statistical test based on confidence intervals.

For the generic drug to be approved, the 90% Confidence Interval (CI) for the ratio of the geometric means (Test/Reference) for both Cmax and AUC must fall entirely within the predetermined equivalence limits of 80.00% to 125.00%.

Let’s break that down:

- Ratio of Means: The study calculates the average Cmax and AUC for the test drug and the reference drug and then finds the ratio (T/R). A perfect match would be a ratio of 1.00 (or 100%).

- Confidence Interval: This is a range of values that is likely to contain the true population ratio. A 90% CI means that we are 90% confident that the true ratio for the entire population lies within this range.

- The 80-125% Window: This window was established based on clinical and pharmacological considerations. It represents a range where any difference in absorption is considered not to be clinically significant. It is a strict standard. Contrary to a common misconception, it does not mean the generic can have 20% less or 25% more drug. The average T/R ratio must be very close to 100%, and the entire statistical range of uncertainty (the 90% CI) must be tightly contained within the 80-125% boundaries.

Passing this statistical test is the make-or-break moment for the ANDA. A “failed” BE study, where the confidence interval for Cmax or AUC falls even slightly outside the 80-125% window, means the product cannot be approved. The company would have to investigate the cause—was it a formulation issue? A problem with the study conduct?—and likely reformulate and repeat the costly study.

When BE Studies Get Complicated: Complex Generics

The classic blood-level BE study works beautifully for drugs that are absorbed systemically, like most oral tablets and capsules. But what about drugs that act locally and are not intended to be absorbed into the bloodstream? This is the realm of complex generics, and it’s one of the fastest-growing and most challenging areas of the industry.

Examples include:

- Topical drugs: Creams, ointments, and gels applied to the skin.

- Inhaled drugs: Products for asthma or COPD delivered via inhalers or nebulizers.

- Ophthalmic drugs: Eye drops.

- Long-acting injectables: Depot formulations that release a drug over weeks or months.

For these products, measuring blood levels is often irrelevant or impossible. The FDA and the industry have had to develop new, sophisticated methods to demonstrate bioequivalence.

In Vitro Release Testing (IVRT) and In Vitro Permeation Testing (IVPT)

For topical products like creams, the key is to show that the generic releases the drug from its formulation and can permeate the skin’s outer layers in the same way as the brand. Instead of human studies, this often relies on lab-based (in vitro) methods:

- In Vitro Release Testing (IVRT): Uses a synthetic membrane in a special apparatus called a Franz diffusion cell to measure the rate at which the API is released from the semi-solid formulation. The generic must show a similar release profile to the brand.

- In Vitro Permeation Testing (IVPT): Is a step closer to reality. It uses excised human skin in the diffusion cell to measure the rate and extent to which the API permeates into the skin layers.

These lab-based tests, combined with rigorous characterization of the formulation’s physical and chemical properties (like pH, viscosity, and globule size), can sometimes be used in place of a traditional clinical study to establish BE.

For other complex products, like inhaled drugs, the approach is different. It might involve showing that the generic inhaler delivers a particle size distribution equivalent to the brand’s device, combined with a PK study. For long-acting injectables, it might involve a long-term PK study in patients. The regulatory and scientific path for each type of complex generic is unique and requires deep expertise.

The Clinical Study Ecosystem

Generic companies are experts in drug development and manufacturing, but they rarely conduct their own clinical studies. This highly specialized work is almost always outsourced to a Clinical Research Organization (CRO).

Partnering with Clinical Research Organizations (CROs)

CROs are the engine room of clinical research. They specialize in running studies efficiently and in compliance with all regulatory standards. Their services include:

- Protocol Development: Working with the generic company to design the BE study protocol.

- Regulatory Submissions: Submitting the protocol to regulatory agencies and ethics committees for approval.

- Subject Recruitment: Finding and screening healthy volunteers who meet the study’s inclusion criteria.

- Clinical Conduct: Housing the volunteers, administering the drugs, collecting the blood samples, and monitoring for any adverse events.

- Bioanalysis: Running the thousands of blood samples through validated analytical methods (usually LC-MS/MS) to generate the plasma concentration data.

- Statistical Analysis and Reporting: Performing the PK and statistical calculations and writing the final clinical study report (CSR) that will be included in the ANDA.

Selecting the right CRO is a critical decision. The generic company will audit the CRO’s facilities and quality systems to ensure they are up to snuff. Any errors in the conduct of the study or the analysis of the samples could invalidate the results and sink the entire project.

Ethical Considerations and Good Clinical Practice (GCP)

All research involving human subjects is governed by strict ethical principles and regulations. In the U.S. and internationally, studies must be conducted according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standards. This framework ensures the rights, safety, and well-being of trial participants are protected and that the clinical trial data are credible.

Key elements of GCP include:

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) / Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) Approval: Before a single subject is enrolled, the study protocol must be reviewed and approved by an independent committee that weighs the risks and benefits of the research.

- Informed Consent: Every volunteer must be fully informed about the purpose, procedures, risks, and potential benefits of the study before agreeing to participate. This is a process, not just a form, and the volunteer can withdraw at any time without penalty.

- Data Integrity and Traceability: All data must be meticulously recorded, and any changes must be documented. The entire study must be auditable, from the original source data to the final report.

Adherence to GCP is not optional. It is a legal and ethical requirement. An FDA inspector can and will audit the CRO’s facilities and records. A finding of significant non-compliance could lead to the rejection of the study data and the entire ANDA. The human element is the final and most important test of the product’s quality before it is submitted for approval.

Stage 4: The Regulatory Marathon – Assembling and Submitting the ANDA

After years of strategic planning, laboratory work, and clinical testing, the finish line appears to be in sight. But the final leg of the journey is not a sprint; it’s a marathon of its own. This is the regulatory phase, where all the disparate threads of development are woven together into a single, comprehensive narrative—the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This document, often running to hundreds of thousands of pages, is the formal request to the FDA to market a generic drug. Assembling it perfectly and navigating the review process is an art form that requires precision, patience, and persistence.

The Common Technical Document (eCTD): A Universal Language for Regulators

In the past, every country had its own unique format for regulatory submissions, creating a nightmare of paperwork for global pharmaceutical companies. To solve this, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) developed the Common Technical Document (CTD), a standardized format now accepted by major regulators worldwide, including the FDA, EMA (European Medicines Agency), and Japan’s PMDA.

Today, all submissions are made electronically in the eCTD format. The eCTD organizes the vast amount of information into a hierarchical structure of five modules, much like a digital five-drawer filing cabinet. This harmonization makes it easier for companies to prepare submissions and for regulators to review them efficiently.

Module 1: Administrative Information

This module contains region-specific administrative and prescribing information. It’s not part of the harmonized CTD but is required by each agency. For an ANDA submitted to the FDA, this module includes:

- Application Forms (Form 356h): The official paperwork requesting approval.

- Draft Labeling: The proposed prescribing information, patient information leaflets, and container labels for the generic product.

- Patent Certifications: The critical Paragraph I, II, III, or IV certifications regarding the brand’s patents.

- Debarment Certification: A statement certifying that the company has not used the services of any person debarred by the FDA.

Module 2: Summaries

This module provides the executive summary of the entire application. It’s where the applicant tells the story of their product and makes the case for its approval. It contains high-level summaries of the Quality (CMC), Nonclinical, and Clinical data found in the other modules. For an ANDA, the most important parts are the Quality Overall Summary (QOS) and the Summary of Bioequivalence. This module is the first thing a reviewer reads, so its clarity and persuasiveness are crucial.

Module 3: Quality (CMC – Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls)

This is the scientific heart of the ANDA and by far the largest and most complex module. It contains every detail about the product’s composition, development, manufacturing process, quality control, and stability. Think of it as the complete biography of the drug product. Key sections include:

- Drug Substance (API): Detailed information about the API manufacturer, synthesis process, characterization, and quality control specifications. This section often cross-references the API supplier’s confidential Drug Master File (DMF).

- Drug Product: A complete description of the generic product itself. This includes the formulation development report (explaining why the excipients were chosen), the manufacturing process description and controls, the specifications for the finished product, the validation of the analytical methods used, and the complete stability data package.

Reviewers from the FDA’s Office of Pharmaceutical Quality will scrutinize this module to ensure the product is well-characterized and can be manufactured consistently to produce a high-quality drug, batch after batch.

Module 4: Nonclinical Study Reports

For a generic ANDA, this module is typically empty or very small. Since the generic relies on the FDA’s previous finding of safety for the brand drug, new nonclinical (animal) toxicology studies are not required.

Module 5: Clinical Study Reports

This module contains the evidence that the generic performs the same way as the brand in humans. For most generics, this means the full Clinical Study Report (CSR) from the bioequivalence study. The CSR is an exhaustive document that includes the study protocol, the statistical analysis plan, information on the subjects, all the raw data, the statistical results, and the final conclusions. An FDA clinical pharmacologist will review this module to confirm that the BE study was conducted properly and that the statistical analysis demonstrates that the generic meets the 90% confidence interval criteria of 80-125%.

The Submission Process: Hitting “Send” on Years of Work

Once all modules are complete and have passed a rigorous internal review, the eCTD is compiled and submitted to the FDA through its Electronic Submissions Gateway (ESG). This is a momentous occasion for the development team, but it’s only the beginning of the review process.

The GDUFA Clock: FDA Review Timelines

The review of generic drugs is governed by the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). Under GDUFA, generic companies pay user fees to the FDA, which in turn provides the agency with the resources to hire more reviewers and adhere to specific performance goals for review times.

When an ANDA is submitted, it is assigned a GDUFA goal date, which is the target date by which the FDA intends to complete its review. For a standard ANDA, this is typically 10 months. For priority reviews (e.g., for drugs in shortage or first generics), the timeline may be shorter. This “GDUFA clock” creates predictability in the process, but the clock can be stopped and restarted depending on the review’s progress.

Refuse-to-Receive (RTR): Avoiding an Early Stumble

Before the formal review even begins, the ANDA undergoes an initial administrative check by the FDA to ensure it is complete enough to be reviewed. If the application is missing major components or is poorly organized, the FDA can issue a Refuse-to-Receive (RTR) letter.

An RTR is a major setback. It means the application is not even accepted into the review queue. The company must fix the deficiencies and resubmit the entire application, which restarts the GDUFA clock from day zero. Common reasons for an RTR include a missing stability data, an inadequate justification for impurities, or a flawed BE study design. Meticulous preparation and pre-submission checks are the best way to avoid this early and costly stumble.

Surviving the Review Cycle: Responding to FDA Information Requests (IRs) and Complete Response Letters (CRLs)

Once the ANDA is accepted for review, different teams of FDA experts (chemistry, bioequivalence, labeling, etc.) begin their work in parallel. It is very rare for an ANDA to be approved in the first cycle without any questions from the agency. The review is an interactive, iterative process.

The Deficiency Letter: A Call to Action

During the review, the FDA may have questions or require clarification on certain points. They will communicate these to the applicant through Information Requests (IRs) or Discipline Review Letters (DRLs). These are informal communications that identify deficiencies that need to be addressed. The company is given a short window (often 7-30 days) to respond. A prompt, clear, and scientifically sound response is critical to keeping the review on track.

If the deficiencies are more significant and cannot be resolved through informal requests, the FDA will issue a Complete Response Letter (CRL) at the end of the 10-month review cycle. A CRL is not a final rejection. It is a formal letter detailing all the deficiencies that prevent the FDA from approving the ANDA in its present form. The GDUFA clock stops upon issuance of a CRL.

A CRL might list chemistry deficiencies (e.g., “Your proposed specification for impurity X is not adequately justified”), bioequivalence issues (e.g., “There were GCP violations at your clinical site”), or labeling problems (e.g., “Your proposed label does not match the current RLD label”).

Crafting a Complete Response: Strategy and Execution

Receiving a CRL can be demoralizing, but it’s a normal part of the process. The key is how the company responds. A cross-functional team is assembled to dissect the CRL and develop a response strategy.

- Minor Deficiencies: If the issues are straightforward (e.g., providing more justification or reanalyzing data), the company can often respond quickly. The FDA will classify this as a “minor amendment,” and the review goal for the response is typically 3 months.

- Major Deficiencies: If the CRL requires new data to be generated—for example, a new short-term stability study, reformulation work, or, in the worst-case scenario, a repeat of the bioequivalence study—the response will take much longer. This is a “major amendment,” and the FDA review clock for the response is reset to 10 months.

Crafting the response is a major undertaking. It must directly address every single point raised in the CRL, providing the necessary data, scientific arguments, and updated documentation. The goal is to provide a package so complete and convincing that the next action from the FDA is an approval letter. Many ANDAs go through two or even three review cycles before finally gaining approval.

Stage 5: The Final Mile – Pre-Approval Inspection and Launch Preparation

Gaining tentative approval or a Complete Response Letter that lists only a pending facility inspection means the ANDA is on the one-yard line. The science is sound, the data are acceptable, but the FDA needs to verify one last thing: can you actually make this product consistently and in compliance with U.S. quality standards? This is the purpose of the Pre-Approval Inspection (PAI). Simultaneously, the commercial teams are shifting into high gear, preparing for the complex logistics of a product launch. This final mile is where regulatory compliance meets commercial execution.

The FDA Knocks: Pre-Approval Inspections (PAIs)

The FDA does not approve a drug based on paperwork alone. They need to see the manufacturing facilities with their own eyes. The PAI is an on-site audit conducted by FDA inspectors at the facilities responsible for manufacturing, packaging, labeling, and testing the drug product, as well as the facility that makes the API.

What Are They Looking For? cGMP Compliance

The overarching goal of the PAI is to verify that the facility is operating in a state of control and in compliance with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). These are the regulations (21 CFR Parts 210 and 211) that establish the minimum requirements for all aspects of drug production and quality control.

During a PAI, inspectors will:

- Compare Reality to the ANDA: They will verify that the manufacturing process, equipment, and controls used in the facility match what was described in the Quality/CMC section of the ANDA. Any discrepancies are a major red flag.

- Audit the Quality System: They will perform a deep dive into the company’s quality system, reviewing procedures for batch records, change control, deviation investigations, handling of out-of-spec (OOS) results, training programs, and internal audits.

- Review Data Integrity: This is a major focus of modern inspections. Inspectors will scrutinize electronic and paper-based data to ensure it is complete, consistent, and accurate. They look for evidence of data manipulation, trial testing, or deletion of unfavorable results.

- Tour the Facility: They will walk through the warehouse, manufacturing suites, and quality control labs to observe operations, check equipment calibration and cleaning logs, and interview personnel.

At the end of the inspection, the inspectors will hold a closeout meeting and may issue a Form 483, which lists any observed deviations from cGMP. These observations must be addressed with a robust corrective and preventive action (CAPA) plan. A successful PAI is a prerequisite for final approval. A failed PAI can put an indefinite hold on the application until all issues are resolved to the FDA’s satisfaction.

Preparing for the Inspection: Mock Audits and Readiness

Companies do not wait for the FDA to show up unannounced. They prepare for months, treating inspection readiness as a continuous process. A common practice is to hire third-party consultants, often former FDA inspectors, to conduct rigorous mock audits.

These mock audits simulate the real thing, identifying gaps and weaknesses in the quality system so they can be fixed before the official inspection. The facility is brought to a state of “inspection readiness,” where all documentation is organized, personnel are trained on how to interact with inspectors, and the entire site is prepared to demonstrate its commitment to quality.

Gearing Up for Go-Time: Commercial Manufacturing and Supply Chain

While the regulatory and quality teams are focused on approval, the commercial and supply chain teams are planning the launch. A generic launch, particularly a “first generic” launch, is an explosive event. The company needs to have millions of doses ready to ship to wholesalers across the country on Day 1.

Tech Transfer and Validation Batches

The manufacturing process developed in the pilot plant must be successfully transferred to the commercial manufacturing site. This technology transfer involves training the commercial operators, qualifying the large-scale equipment, and ensuring the process works as expected at its final scale.

Before commercial production can begin, the company must manufacture process validation (PV) batches. These are the first few full-scale commercial batches, typically three, that are intensively monitored and tested to formally prove that the manufacturing process is robust, reproducible, and consistently delivers a product that meets its pre-determined quality specifications. The data from these batches form the final confirmation of the process’s validity.

Building Inventory: The At-Risk Launch Decision

Here lies one of the biggest gambles in the pharmaceutical industry. To have product ready for a Day 1 launch, a company must often begin manufacturing large quantities of the drug before it has received final FDA approval. This is known as producing “at-risk” inventory.

Why is it a risk?

- If the ANDA is not approved, or if the launch is delayed due to patent litigation, the company could be stuck with millions of dollars’ worth of inventory that it cannot sell and may have to destroy.

- If the company launches while patent litigation is still pending (an “at-risk launch”), and subsequently loses the patent case, they could be liable for massive damages to the brand company, potentially amounting to all the profits they made from the generic.

Despite the risks, building inventory is often a commercial necessity. Wholesalers and pharmacy chains need assurance that there will be a continuous and reliable supply. A company that isn’t ready to flood the market on launch day will quickly lose market share to competitors who are. The decision of how much inventory to build and when is a high-stakes calculation balancing regulatory uncertainty, litigation risk, and commercial opportunity.

The Launch Sequence: Marketing, Sales, and Pharmacovigilance

With final approval in hand and inventory in the warehouse, the launch sequence is initiated.

Pricing and Reimbursement Strategy

The commercial team executes its pricing strategy. For a “first generic” with 180-day exclusivity, the price might be set at a modest discount to the brand (e.g., 10-20% less). When multiple generics enter, the price can plummet by 90% or more due to intense competition. The company’s sales and national account teams work with the major drug wholesalers (like McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen) and large pharmacy chains to secure contracts and ensure the product is stocked and available. They also work with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to ensure the drug is placed on formularies, making it easily accessible to patients through their insurance plans.

Post-Market Surveillance and Safety Reporting

The company’s responsibility does not end when the product leaves the warehouse. All drug manufacturers are required to have a pharmacovigilance system to monitor the real-world safety of their products.

This involves:

- Collecting and investigating any Adverse Event Reports (AERs) that come in from patients, doctors, or pharmacists.

- Reporting serious and unexpected adverse events to the FDA in an expedited manner.

- Submitting periodic safety update reports to the agency.

- Monitoring the medical literature for any new safety information about the drug.

This post-market surveillance ensures that the safety profile of the drug is continuously monitored throughout its lifecycle, protecting patients and maintaining public trust in the quality of generic medicines. The journey from molecule to market is complete, but the commitment to quality and safety is ongoing.

The Global Arena: Harmonization and Divergence in Generic Drug Regulation

While this guide has focused heavily on the U.S. FDA and the Hatch-Waxman framework, the generic drug industry is a thoroughly global enterprise. A large generic company based in India, Israel, or Europe may seek to market its products in dozens of countries simultaneously. This requires navigating a complex patchwork of global regulations. While there are powerful forces driving harmonization, significant and tricky differences between major markets persist.

Beyond the FDA: The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Other Key Regulators

The second-largest developed pharmaceutical market is the European Union, regulated by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The EMA’s approach to generics is conceptually similar to the FDA’s, but with important differences in procedure and terminology.

- Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA): In Europe, a generic application is known as a Marketing Authorisation Application submitted via the “generic application” procedure, which is analogous to the ANDA.

- Reference Medicinal Product (RMP): This is the European equivalent of the FDA’s Reference Listed Drug (RLD).

- Data Exclusivity: Europe has a system known as “8+2+1”. An innovator gets 8 years of data exclusivity (during which a generic application cannot be filed), followed by 2 years of market exclusivity (during which a generic can be approved but not marketed). An additional 1 year of market exclusivity can be granted if the innovator gets a new indication approved during the first 8 years. This system is different from the U.S. model of 5-year NCE exclusivity and patent-linked stays.

- No Patent Linkage: Crucially, unlike the FDA, the EMA does not “link” marketing approval to patent status. The EMA will grant a marketing authorization for a generic even if the brand’s patents are still in force. It is the generic company’s own commercial responsibility and legal risk to decide when to launch, based on the patent situation in each individual EU member state. Patents are national rights, and litigation occurs on a country-by-country basis.

Other major regulators, like Health Canada, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), and Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), have their own unique variations on these themes, each with specific data requirements, review timelines, and legal frameworks that companies must master.

The ICH and the Quest for Harmonization

The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) has been the single most important force in reducing the regulatory friction between these different regions. The ICH brings together regulators and industry experts from around the world to develop common guidelines for drug development.

The adoption of ICH guidelines, such as the Common Technical Document (CTD), has been a game-changer. It allows a company to create a core “global dossier” for a product (especially the Quality/CMC module) that can be used as the basis for submissions in all ICH regions, with only minor regional customizations needed. Other key ICH guidelines cover topics like stability testing (the Q1 series), impurity thresholds (the Q3 series), and good manufacturing practice (the Q7 guide for APIs), creating a common scientific language and set of expectations for quality worldwide.

Local Hurdles: Country-Specific Requirements

Despite harmonization, global submission strategies are still complex. Companies must deal with a host of local requirements:

- Labeling and Language: Product information must be translated and formatted according to the specific rules of each country.

- Pharmacopoeial Standards: While the major pharmacopoeias (USP, Ph. Eur., JP) are largely harmonized, there can be differences in specific test methods or acceptance criteria that must be addressed.

- API Sourcing: Some countries have rules that favor locally produced APIs or require additional registration steps for foreign API manufacturers.

- BE Study Populations: Some regulators may require BE studies to be conducted in their local population if there is reason to believe ethnicity could affect pharmacokinetics.

Successfully launching a product globally requires a sophisticated regulatory affairs department that can manage these parallel and sometimes conflicting requirements, creating a master plan that gets the product to patients around the world as efficiently as possible.

The Future of Generics: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities

The generic drug industry, born from a legislative compromise in 1984, has matured into a global powerhouse. But it is not a static industry. It is constantly evolving in response to new scientific frontiers, shifting market dynamics, and emerging technologies. The future of generics will be defined by increasing complexity, a greater emphasis on value, and the adoption of digital tools to accelerate development.

The Rise of Biosimilars: The Next Frontier

Perhaps the most significant evolution is the expansion from small-molecule generics to biosimilars. Biologics—large, complex molecules like monoclonal antibodies that are produced in living cell systems—are the dominant force in modern medicine, treating cancer, autoimmune diseases, and more. As the first wave of these blockbuster biologics loses patent protection, a new pathway for “similar” versions has emerged.

Developing a biosimilar is an order of magnitude more complex and expensive than a traditional generic:

- Manufacturing Complexity: Reproducing a large protein with its exact three-dimensional structure and post-translational modifications is a monumental scientific challenge. The process defines the product.

- Extensive Analytics: Proving “similarity” requires a massive battery of sophisticated analytical tests to compare hundreds of quality attributes between the biosimilar and the reference biologic.

- Clinical Requirements: Unlike generics, biosimilars typically require comparative clinical studies, including a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) study and often a comparative efficacy and safety trial in patients, to demonstrate that there are no clinically meaningful differences.

The cost to develop a biosimilar can be $100-$300 million, compared to $1-$5 million for a simple generic. However, the market opportunities are enormous, and this “next frontier” will be a major growth driver for the industry for decades to come.

The Push for “Supergenerics” and Value-Added Medicines

As the market for simple, “plain vanilla” generics becomes increasingly crowded and commoditized, many companies are shifting their focus to more complex products. This includes the complex generics we’ve discussed (inhalers, topicals) but also a category often called “supergenerics” or value-added medicines.

These are not direct copies. Instead, they leverage an existing, well-understood API to create a new, improved product that offers a tangible benefit. This is often pursued through the FDA’s 505(b)(2) pathway, which is a hybrid between an ANDA and a full New Drug Application (NDA). Examples include:

- New Formulations: Creating an extended-release version of an immediate-release drug to reduce dosing frequency.

- New Dosage Forms: Developing an oral liquid or a dissolvable film for patients who have difficulty swallowing tablets.

- New Combinations: Combining two existing generic drugs into a single fixed-dose combination pill to improve convenience and adherence.

These value-added products can gain their own patents and exclusivities, offering a way to escape the intense price competition of the pure generic market and create differentiated, more profitable products.

Digital Transformation and AI in Generic Development

Like all industries, pharmaceutical development is being transformed by data science, automation, and artificial intelligence (AI). Generic companies are increasingly adopting these tools to gain an edge.

- AI in Portfolio Selection: Machine learning algorithms can analyze vast datasets on market trends, patent litigation, and scientific literature to help identify high-potential generic candidates with a greater degree of accuracy.

- Automation in the Lab: Robotic systems can automate routine tasks like sample preparation and dissolution testing, increasing throughput and reducing human error.

- In Silico Modeling: Computer simulations can model and predict how a formulation will behave or how a drug will be absorbed in the body (in silico bioequivalence). This can reduce the number of costly lab experiments and pilot BE studies needed, accelerating development timelines.

- Smart Manufacturing (Pharma 4.0): The integration of sensors, data analytics, and continuous manufacturing processes allows for real-time monitoring and control of quality, making production more efficient and reliable.

While the adoption of these advanced technologies is still in its early stages, they hold the promise of making the generic drug development process faster, cheaper, and more predictable in the years to come.

Conclusion: The Enduring Value of the Generic Promise

The journey from molecule to market is a testament to the power of integrating deep science, sharp legal strategy, and operational excellence. It is a process that begins not with a chemical reaction, but with a strategic analysis of patents and markets. It navigates a labyrinth of meticulous formulation, rigorous analytics, and demanding human studies. It culminates in a regulatory marathon, where years of work are condensed into a massive digital dossier, scrutinized by experts who serve as guardians of public health.

The generic drug industry is far more than a business of imitation. It is an engine of access and a pillar of healthcare sustainability. Every successful ANDA approval represents a victory for patients, providing them with affordable access to the medicines they need to live healthier lives. It is a victory for healthcare systems, freeing up vital resources that can be channeled back into the innovation that will produce the blockbuster drugs of tomorrow.

For the professionals who dedicate their careers to this field, the work is challenging, the stakes are high, and the pressure is immense. But the reward is the knowledge that they are part of a critical mission: fulfilling the promise of modern medicine by placing it within reach of everyone. The process is complex, the path is arduous, but the value created at the end of that path is immeasurable and enduring.

<br>

Key Takeaways

- Strategy is Paramount: The most critical decisions in generic development are made before any lab work begins. Success depends on a masterful strategy for candidate selection, patent analysis (using tools like DrugPatentWatch), and risk assessment.

- Hatch-Waxman is the Rulebook: The entire U.S. generic industry operates within the framework of the Hatch-Waxman Act. Understanding its provisions, especially Paragraph IV certifications and the 180-day exclusivity, is fundamental to competitive strategy.

- Bioequivalence is the Scientific Core: The linchpin of a generic approval is the demonstration of bioequivalence (BE) to the brand-name drug. For most oral drugs, this is proven via a pharmacokinetic study showing the 90% confidence intervals for Cmax and AUC fall within 80-125%.

- Quality is Built-In, Not Tested-In: The modern approach to development is Quality by Design (QbD). This systematic method focuses on understanding the product and process deeply to ensure consistent quality, reducing manufacturing failures and regulatory delays.

- The ANDA is a Regulatory Marathon: Assembling and submitting the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) in the eCTD format is a massive undertaking. Successfully navigating the FDA’s multi-cycle review process requires expertise, persistence, and a rapid-response capability to address agency questions.

- Complexity is the New Frontier: The future of the industry lies in tackling more complex products. This includes not only technically challenging generics (inhalers, injectables) but also biosimilars and value-added medicines that offer new benefits beyond simple substitution.

<br>

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the single most common reason an ANDA receives a Complete Response Letter (CRL) on the first review cycle?

While reasons vary, deficiencies related to Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC), found in Module 3 of the ANDA, are consistently the most frequent cause. These can range from an inadequately justified impurity specification or an incomplete stability data package to insufficient validation of an analytical method. It highlights that even with a successful bioequivalence study, the FDA’s intense focus on product quality and manufacturing consistency means that the CMC section must be flawless.

2. How does an “authorized generic” differ from a regular generic, and how does it impact strategy?

An authorized generic (AG) is the exact same brand-name drug, but marketed without the brand name on its label. It is launched by the brand company itself (or with a partner) and does not require an ANDA. Brand companies often launch an AG on the same day the first “true” generic competitor with 180-day exclusivity launches. This is a strategic move to cannibalize the first filer’s sales and retain market share. A generic company’s commercial forecast must always account for the high probability of AG competition, which can significantly reduce the profitability of the 180-day exclusivity period.

3. What is “data integrity” and why has it become such a major focus for FDA inspections?

Data integrity refers to the completeness, consistency, and accuracy of data. For the FDA, it’s the foundation of trust. In recent years, inspectors have uncovered instances (particularly in some overseas facilities) of fraudulent practices like manipulating test results, hiding failing data, or backdating records. As a result, inspectors now use sophisticated forensic techniques to audit electronic and paper data trails. A facility with poor data integrity practices, even without evidence of fraud, will fail its inspection because the FDA cannot trust any of the data submitted in the ANDA. It has become a make-or-break issue for approval.

4. How is AI practically being used to accelerate generic development today, beyond just hype?