Executive Summary

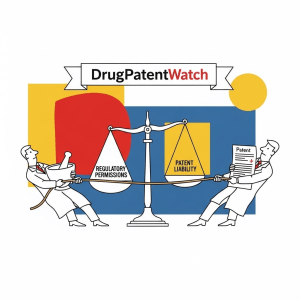

The pharmaceutical sector currently faces a distinct legal friction where federal health policy conflicts with intellectual property statutes. On one side, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) maintains a regulatory framework that permits, and in times of shortage encourages, the compounding of drugs to meet specific patient needs. On the other, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) grants patent holders an exclusionary right that contains no explicit exemption for pharmacy compounding. This divergence creates a substantial liability risk for compounding pharmacies, investors, and healthcare providers.

The fundamental query—whether a compounding pharmacy can legally manufacture a patented drug pursuant to a prescription—requires a bifurcated answer. From a regulatory perspective under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), the answer is qualifiedly yes, provided specific conditions regarding medical necessity or drug shortages are met. From a patent law perspective under 35 U.S.C., the answer is generally no. A valid patent grants the owner the absolute right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention, regardless of the infringer’s regulatory compliance or public health intent.

This report analyzes the statutory mechanics of this conflict. It examines the limitations of the “medical practitioner” exemption under 35 U.S.C. § 287(c), the failure of the “safe harbor” provision of § 271(e)(1) to protect commercial compounding, and the aggressive litigation strategies currently deployed by major pharmaceutical manufacturers against the compounding sector. With the market for compounded GLP-1 agonists (such as semaglutide and tirzepatide) reaching multi-billion dollar valuations, the enforcement of intellectual property rights against compounders has shifted from sporadic cease-and-desist actions to systemic, high-value litigation.

Industry Statistic

“The global GLP-1 agonists weight loss drugs market size was estimated at USD 13.84 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 48.84 billion by 2030… driven by rising obesity rates… and strong clinical efficacy of drugs like semaglutide.”

1

For business professionals, legal counsel, and investors, understanding this liability structure is critical. The assumption that FDA compliance creates a shield against patent infringement is a legal fallacy that exposes entities to significant financial damages. This report outlines the specific legal vulnerabilities inherent in the 503A and 503B business models and provides a data-driven framework for assessing Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) in this volatile sector.

The Regulatory Dichotomy: FDA Permissions versus Patent Prohibitions

To accurately assess risk, one must distinguish between the permission to market a drug (regulatory law) and the right to manufacture a patented invention (patent law). These two systems operate independently. Compliance with one does not immunize an entity from liability under the other.

The FD&C Act Framework: 503A and 503B

Congress has established two primary legal pathways for pharmacy compounding, codified in Sections 503A and 503B of the FD&C Act. These sections provide exemptions from three key requirements that apply to conventional drug manufacturers: the requirement to obtain a New Drug Application (NDA) approval (Section 505), the requirement to label drugs with adequate directions for use (Section 502(f)(1)), and, for 503A pharmacies, the requirement to comply with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP).2

Section 503A: The Traditional Pharmacy

Section 503A regulates traditional compounding. These entities must operate pursuant to a patient-specific prescription. They are prohibited from compounding large batches in anticipation of orders, except in very limited quantities based on historical prescribing patterns. The primary limitation for 503A pharmacies regarding commercial copies is the prohibition on compounding “regularly or in inordinate amounts” any drug products that are essentially copies of a commercially available drug product.4

Section 503B: The Outsourcing Facility

Enacted following the 2012 fungal meningitis outbreak caused by the New England Compounding Center, the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA) created Section 503B. This designation allows facilities to register as “outsourcing facilities.” Unlike 503A pharmacies, 503B facilities may compound drugs in bulk without patient-specific prescriptions for distribution to healthcare providers (office stock). In exchange for this commercial flexibility, 503B facilities must comply with full CGMP standards and submit to FDA inspections.3

Table 1: Operational and Regulatory Distinctions between 503A and 503B Facilities

| Feature | 503A Pharmacy | 503B Outsourcing Facility |

| Primary Customer | Individual Patient (Home Use) | Healthcare Facilities / Physicians (Office Use) |

| Prescription Requirement | Required for every unit dispensed | Not required; bulk distribution permitted |

| Batch Size | Limited to specific patient need | Unlimited (subject to CGMP) |

| CGMP Compliance | Exempt (follows USP /) | Mandatory (21 CFR Parts 210 & 211) |

| “Essentially a Copy” Rule | Restricted (“regular or inordinate amounts”) | Strictly Prohibited (unless on shortage list) |

| Patent Infringement Risk | Moderate (lower volume, harder to detect) | High (industrial scale, direct competitor) |

3

The Patent Act’s Strict Liability Standard

While the FDA grants these exemptions to ensure patient access to tailored medications, the Patent Act confers a “right to exclude.” Section 271(a) of the Patent Act establishes that “whoever without authority makes, uses, offers to sell, or sells any patented invention, within the United States or imports into the United States any patented invention during the term of the patent therefor, infringes the patent”.7

This statutory language creates a strict liability standard. The intent of the infringer is irrelevant to the finding of infringement (though it impacts damages). The fact that a pharmacist is acting in the interest of patient health, or complying with FDA compounding regulations, serves as no defense against a charge of literal infringement. If a compounding pharmacy creates a formulation that reads on the claims of a valid patent—whether that patent covers the active ingredient, the formulation, or the method of use—the pharmacy has committed an act of infringement.8

The conflict arises because the FDA exemptions (from NDA requirements) remove the barriers to market entry, while the patent system seeks to maintain barriers to entry to reward innovation. A 503B facility investing in the equipment to produce a sterile injectable drug is building a business model based on the regulatory permission to operate, often failing to account for the patent prohibition that remains in force.

Statutory Immunities and Their Limits

When pharmaceutical companies initiate patent litigation against compounders, defendants typically attempt to invoke specific statutory exemptions designed to protect medical activity. A detailed analysis reveals these exemptions are narrower than commonly believed and often fail to protect commercial compounding operations.

The Medical Practitioner Exemption: 35 U.S.C. § 287(c)

The most frequently cited defense is the “medical practitioner exemption.” Enacted in 1996 following the controversial lawsuit Pallin v. Singer, where a physician sued another for using a patented incision technique, § 287(c) limits the ability of patent holders to enforce patents against medical professionals performing medical activities.10

Statutory Construction and Limitations

Section 287(c)(1) states that with respect to a “medical practitioner’s performance of a medical activity,” the provisions regarding remedies for infringement (damages, injunctions) shall not apply. However, the definition of “medical activity” in § 287(c)(2)(A) contains explicit exclusions that render it ineffective for most pharmacy compounding defenses.11

The statute defines “medical activity” as the performance of a medical or surgical procedure on a body, but specifically excludes:

- The use of a patented machine, manufacture, or composition of matter in violation of such patent.

- The practice of a patented use of a composition of matter in violation of such patent.

- The practice of a process in violation of a biotechnology patent.11

Furthermore, § 287(c)(3) states that the exemption does not apply to the activities of any person engaged in the commercial development, manufacture, sale, importation, or distribution of a machine, manufacture, or composition of matter or the provision of pharmacy or clinical laboratory services.10

Implications for Compounders

This exclusionary language is fatal to the defense of compounding pharmacies.

- Composition of Matter: Most pharmaceutical patents cover the chemical structure of the drug (composition of matter). Since the statute explicitly excludes the use of a patented composition of matter from the definition of “medical activity,” a pharmacist compounding a patented drug cannot claim immunity.13

- Commercial Activity: Compounding pharmacies, especially 503B facilities, are engaged in the commercial manufacture and sale of drugs. The legislative history and the text of § 287(c)(3) clarify that Congress intended to protect the procedure performed by a doctor (e.g., a surgical method), not the product made and sold by a pharmacy or manufacturer.10

Therefore, § 287(c) offers no shield to a pharmacy compounding a drug that infringes a composition of matter patent or a formulation patent.

The Safe Harbor Provision: 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)

Another potential defense is the “Hatch-Waxman Safe Harbor.” This provision exempts acts of infringement that are “solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information under a Federal law which regulates the manufacture, use, or sale of drugs”.14

Applicability to Commercial Compounding

The safe harbor was designed to allow generic manufacturers to conduct bioequivalence testing and prepare regulatory filings (such as an ANDA) before the expiration of a patent, facilitating immediate market entry upon patent expiry.

- The “Solely” Requirement: Courts have interpreted “solely” to exclude routine commercial sales. A 503A or 503B facility selling compounded drugs to patients or hospitals is engaging in commerce, not merely developing data for an FDA submission. The sale is the end goal, not a regulatory step.3

- Classen Immunotherapies Precedent: The Federal Circuit in Classen Immunotherapies v. Biogen IDEC held that the safe harbor does not protect information routinely reported to the FDA post-approval. While 503B facilities must report the drugs they compound to the FDA, this reporting is a condition of their commercial license, not a submission for pre-market approval. Therefore, the routine production and sale of compounded drugs fall outside the protection of § 271(e)(1).14

Consequently, neither § 287(c) nor § 271(e)(1) provides a robust defense for a compounding pharmacy accused of infringing a patent through the sale of compounded medications.

The “Essentially a Copy” Doctrine as a Litigious Weapon

The FDA’s regulatory framework includes provisions designed to protect the integrity of the new drug approval process by restricting compounders from making “copies” of approved drugs. While these are regulatory rules, patent holders effectively utilize them as leverage in intellectual property litigation.

Regulatory Definition of “Essentially a Copy”

The restrictions on copying differ slightly for 503A and 503B entities but share the same policy goal: preventing compounders from serving as unregulated generic manufacturers.

For 503A Pharmacies:

A compounded drug is considered essentially a copy if:

- It consists of the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as a commercially available drug.

- The API has the same, similar, or easily substitutable dosage strength.

- The prescriber does not determine that the compounded formulation makes a significant difference for the individual patient.3

For 503B Outsourcing Facilities:

The standard is stricter. A drug is essentially a copy if:

- It is identical or nearly identical to an approved drug.

- It consists of a bulk drug substance that is a component of an approved drug, unless there is a change that produces a clinical difference for the patient, as determined by the prescribing practitioner.5

Leveraging Regulatory Violations in Patent Suits

Patent holders use these definitions to construct “Unapproved New Drug” arguments. If a compounding pharmacy produces a drug that the FDA would classify as “essentially a copy” (e.g., compounding a tablet identical to a commercial product without a documented medical need like an allergy), the pharmacy loses its exemptions under 503A or 503B.

Once the exemption is lost, the compounded drug becomes an “unapproved new drug” under the FD&C Act. This exposes the pharmacy to liability under the Lanham Act for false advertising. The innovator argues that by selling an unapproved drug that mimics the approved product, the pharmacy is deceiving consumers and engaging in unfair competition.17

The “Salt” Argument and Safety Risks

In the recent disputes involving semaglutide, some compounders utilized salt forms of the API (semaglutide sodium or semaglutide acetate) rather than the base form used in the FDA-approved product (Wegovy/Ozempic). Compounders argued this avoided patent infringement of the base molecule. However, the FDA issued warnings that these salt forms are not components of the approved drugs and raise safety concerns. This places compounders in a bind: use the base form and infringe the patent/violate the “copy” rule, or use the salt form and violate FDA safety warnings, inviting Lanham Act lawsuits for selling “adulterated” or “misbranded” drugs.18

The Shortage List Paradox

The intersection of drug shortages and patent rights represents the most critical area of ambiguity and risk in the current market.

The Mechanism of Section 506E

When a drug is in short supply, the FDA places it on the Drug Shortage List under Section 506E of the FD&C Act.

- Regulatory Effect: The placement of a drug on this list suspends the “essentially a copy” restriction. A 503B facility is statutorily permitted to compound copies of a drug on the shortage list without needing to demonstrate a clinical difference for the patient.3

- Public Policy: This mechanism allows the compounding industry to function as a “relief valve,” rapidly increasing supply to meet patient demand when the approved manufacturer fails to do so.19

The Patent Trap

Crucially, the FDA’s authorization to compound a shortage drug acts only as a waiver of regulatory penalties. It does not suspend the patent rights of the innovator. A patent is a property right granted by Congress, and the FD&C Act does not contain a provision that invalidates or suspends a patent during a declared public health shortage.8

This creates a paradox where a compounder is:

- Encouraged by the FDA to invest capital to manufacture a drug like cisplatin or semaglutide to solve a shortage.

- Liable for Patent Infringement the moment they sell that drug, as the patent holder retains the right to exclude.

Economic Realities vs. Legal Risk

While the patent holder can sue, they often face strategic headwinds during a shortage.

- Injunctive Relief: Courts typically weigh the “public interest” when deciding whether to grant a preliminary injunction. If a drug is in critical shortage (e.g., a cancer drug), a judge may deny an injunction that would cut off supply to patients, even if infringement is likely.8

- Damages: The patent holder can still seek monetary damages (lost profits or reasonable royalties) for the sales made during the shortage.

- Reputational Risk: Suing a pharmacy that is keeping cancer patients alive during a shortage is a public relations disaster. Consequently, enforcement during “true” shortages of life-saving drugs is rare.

However, for “lifestyle” drugs or chronic treatments like GLP-1 agonists, where the shortage is driven by massive consumer demand rather than manufacturing failure, innovators have shown no hesitation in litigating.22

The Biologic Frontier and GLP-1 Litigation

The current legal battlefield is defined by the high-value market for GLP-1 receptor agonists. This conflict illustrates the evolution of litigation strategies against compounders.

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly vs. The Compounding Industry

Semaglutide (Novo Nordisk) and Tirzepatide (Eli Lilly) are peptide-based drugs. While technically distinguishable from large biological molecules, they share complex manufacturing characteristics. The immense demand for these weight-loss drugs created a prolonged shortage, incentivizing thousands of compounders to enter the market.

Litigation Strategy Shifts

Innovators have moved beyond simple patent infringement suits to a broader “Total War” strategy:

- Lanham Act False Advertising: Lawsuits allege that compounders are marketing their products as “generic Ozempic” or “generic Mounjaro.” Since there is no FDA-approved generic, these claims are legally false. This allows innovators to target the marketing of the drug rather than just the chemistry.22

- State Consumer Protection Laws: By testing compounded samples and finding impurities or lower potency, innovators sue under state laws (e.g., Florida Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act), arguing the products are dangerous to consumers.18

- ITC Exclusion Orders: Eli Lilly utilized the International Trade Commission to block the importation of the tirzepatide API, effectively cutting off the supply chain for compounders at the source.25

The “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” List

A key defensive maneuver for innovators is petitioning the FDA to place specific drugs or categories (like peptides or biologics) on the “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” list.

- Effect: If a drug is on this list, it cannot be compounded under 503A or 503B, regardless of whether it is in shortage.

- Current Status: Innovators are actively lobbying for GLP-1s and other complex molecules to be added to this list to permanently close the compounding window.26

Strategic Freedom-to-Operate and Risk Mitigation

For investors and operators in the compounding space, the “wait and see” approach to patent liability is financially perilous. A proactive Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) strategy is required to navigate the overlap of 503B regulations and patent claims.

The FTO Execution Framework

Conducting an FTO for a compounding operation differs from a generic drug launch. The timeline is compressed, and the regulatory pathway does not provide the 30-month stay of litigation afforded to ANDA filers.

Table 2: Compounding Pharmacy FTO Checklist

| Analysis Phase | Key Actions | Tools & Considerations |

| 1. Patent Identification | Identify all Orange Book patents (composition, formulation, method of use). Search for non-Orange Book patents (manufacturing process). | Use DrugPatentWatch to map patent expiration dates and exclusivity periods against shortage projections.27 |

| 2. Regulatory Overlay | Determine 506E Shortage List status. Check “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” list status. | Cross-reference patent claims with the specific formulation allowed under FDA shortage guidance. |

| 3. Claim Construction | Analyze “Method of Use” claims. Does the patent cover all uses or just a specific indication (e.g., heart failure vs. hypertension)? | If the patent covers a specific indication, can the compounder limit prescribing to non-patented uses? (Difficult in practice). |

| 4. Supplier Audits | Verify the API source. Does the API manufacturer hold a license? Do they provide indemnification? | Review supply contracts for patent indemnity clauses.29 |

| 5. Formulation Design | Can excipients be altered to avoid formulation patents? | Determine if changing excipients triggers the “Essentially a Copy” clinical difference requirement. |

27

Using DrugPatentWatch for Strategic Intelligence

Platforms like DrugPatentWatch are essential in this phase. Unlike standard patent search engines, they integrate regulatory data (exclusivity periods, Orange Book codes) with patent data. This allows a user to:

- Identify “Method of Use” patents that might remain active after the composition of matter patent expires.

- Monitor litigation alerts to see if other generic firms or compounders are already being sued on the same assets.

- Forecast generic entry dates, which often correlate with the removal of a drug from the shortage list (as generic entry solves the supply constraint).28

Indemnification and Contractual Protections

Compounding pharmacies must negotiate patent indemnification clauses with their API suppliers.

- The Clause: A provision where the supplier agrees to defend and reimburse the pharmacy for any patent infringement damages arising from the use of the API.

- The Limitation: Suppliers often limit this to the API itself. If the infringement claim arises from the formulation (the mix of API + excipients) or the method of use, the API supplier’s indemnity may not apply. 503B facilities must carefully draft these agreements to cover the final product liability where possible.32

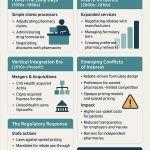

Economic Implications of the Compounding Wedge

The persistence of the compounding market despite legal risks is driven by fundamental economic incentives.

Price Arbitrage

The cost differential between innovator biologics and compounded alternatives creates a massive economic wedge.

- Innovator Pricing: Branded GLP-1s often cost between $900 and $1,300 per month.

- Compounded Pricing: Compounded versions are sold for $200 to $400 per month.

This price elasticity of demand ensures that even with legal risks, the potential revenue for a 503B facility capturing a fraction of the market is substantial. For self-insured employers and patients paying out-of-pocket, the compounded option is often the only financially viable one.33

Insurance and Reimbursement

Generally, commercial insurers and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) are hesitant to cover compounded drugs, citing their “unapproved” status. However, during shortages, some plans grant exceptions. The lack of broad reimbursement acts as a natural cap on the market, but the cash-pay market (especially for lifestyle, anti-aging, and weight loss drugs) remains robust enough to sustain the industry.35

Conclusion

The question of whether compounding pharmacies can make patented drugs pursuant to prescriptions is settled by a collision of opposing legal forces. The FD&C Act provides a permissive pathway driven by public health necessity, while the Patent Act maintains a restrictive barrier driven by property rights.

For the immediate future, the risk remains highest for 503B outsourcing facilities. Their industrial scale and interstate commerce profile make them the primary targets for innovator litigation. While the “shortage loophole” provides a temporary operational window, it is a window made of glass—transparent to patent enforcement and easily shattered by a court order or a shift in FDA policy.

The evolution of this sector will likely be defined by the courts’ interpretation of “implied preemption”—whether the FDA’s statutory authority to manage drug shortages implicitly preempts the strict liability of the Patent Act. Until the Supreme Court or Congress speaks directly to this issue, the compounding of patented drugs remains a high-risk, high-reward arbitrage played in the shadow of potential infringement liability.

Key Takeaways

- Strict Liability Prevails: There is no “public health” or “pharmacy” exemption in the U.S. Patent Act. A pharmacy compounding a patented drug infringes that patent, regardless of FDA compliance or patient need.

- Section 287(c) is Ineffective: The “Medical Practitioner” exemption explicitly excludes pharmacy services and the use of patented compositions of matter. It protects surgeons, not compounders.

- Shortage List ≠ Patent Waiver: The FDA Drug Shortage List allows compounders to bypass the “essentially a copy” regulatory restriction. It does not suspend the patent rights of the innovator.

- The “Unapproved Drug” Pincer: Innovators use the “essentially a copy” rules to frame compounded drugs as “unapproved new drugs,” enabling them to sue for false advertising (Lanham Act) and unfair competition, which often carry faster injunctive relief than patent suits.

- Scale Increases Risk: 503B outsourcing facilities face significantly higher litigation risk than 503A pharmacies due to their larger volume, “office stock” distribution model, and deeper pockets.

FAQ

1. Can a patent holder obtain an injunction to stop a pharmacy from compounding a life-saving drug during a shortage?

Technically, yes, but it is difficult. Courts apply the eBay v. MercExchange four-factor test for injunctions, which includes considering the “public interest.” If a drug is critical for life support (e.g., a cancer drug or epinephrine) and the innovator cannot supply the market, a judge is likely to deny the injunction to prevent patient harm, even if infringement is proven. However, the pharmacy would still be liable for monetary damages.

2. Why don’t generic drug manufacturers use the “shortage loophole” to launch early?

Generic manufacturers operate under Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs), which require certification regarding patents (Paragraph IV certification). Filing an ANDA triggers a statutory 30-month stay of approval if the patent holder sues. Compounders do not file ANDAs, so they don’t trigger this automatic stay. Generics are bound by the formal FDA approval pathway, whereas compounders operate in the exemptions of 503A/503B.

3. Does the “Safe Harbor” (271(e)(1)) apply if a 503B facility is conducting stability testing for FDA reporting?

It is a gray area, but likely no for the commercial product. While the testing itself might be protected, the production of the commercial batches sold to hospitals is not “solely” for the development of information for the FDA. The sale is the primary purpose. The Safe Harbor typically protects pre-market research, not post-market commercial compliance.

4. How does the “Demonstrably Difficult to Compound” list affect patent strategy?

It is a regulatory “kill switch.” If an innovator succeeds in lobbying the FDA to place their drug on this list (common for complex delivery systems or biologics), compounding becomes illegal under the FD&C Act immediately. This renders the patent question moot, as the FDA will shut down the operation for regulatory violations, saving the innovator the cost of patent litigation.

5. Can a physician be sued for prescribing a compounded version of a patented drug?

Generally, no. Physicians are usually protected under the “Medical Practitioner” exemption (35 U.S.C. § 287(c)) for their medical activities, including prescribing. However, if a physician is significantly involved in the commercialization—for example, owning a stake in the compounding pharmacy or inducing the pharmacy to infringe—they could potentially be liable for induced infringement, though this is rare.

Works cited

- GLP-1 Agonists Weight Loss Drugs Market Size Report, 2030 – Grand View Research, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/glp-1-agonists-weight-loss-drugs-market-report

- The Viability of a Compounding Pharmacy Patent Exception in the United States, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/health_law/resources/esource/archive/viability-compounding-pharmacy-patent-exception-united-states/

- Breaking Down Patent Barriers: A Guide for Compounding Pharmacies – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/breaking-down-patent-barriers-a-guide-for-compounding-pharmacies/

- Product Under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act Guidance for Industry – FDA, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Compounded-Drug-Products-That-Are-Essentially-Copies-of-a-Commercially-Available-Drug-Product-Under-Section-503A-of-the-Federal-Food–Drug–and-Cosmetic-Act-Guidance-for-Industry.pdf

- Compounded Drug Products That Are Essentially Copies of Approved Drug Products Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act – FDA, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/media/98964/download

- ASHP Guidelines on Outsourcing Sterile Compounding Services, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.ashp.org/Outsourcing-Compounding-Services

- Patent Infringement in Personalized Medicine: Limitations of the Existing Exemption Mechanisms, accessed December 19, 2025, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6351&context=law_lawreview

- Compounding Inequities Through Drug IP and Unfair Competition – Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW, accessed December 19, 2025, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ipipc_papers

- Intellectual Property Challenges for 503A Pharmacy Compounding – Frier Levitt, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.frierlevitt.com/articles/intellectual-property-challenges-for-503a-pharmacy-compounding/

- Remedies Under Patents On Medical And Surgical Procedures | Oblon, McClelland, Maier & Neustadt, L.L.P., accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.oblon.com/publications/remedies-under-patents-on-medical-and-surgical-procedures

- 35 U.S. Code § 287 – Limitation on damages and other remedies; marking and notice, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/35/287

- Protecting Innocent Infringers of Naturally Reproducing Patented Organisms – Stetson University, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www2.stetson.edu/advocacy-journal/protecting-innocent-infringers-of-naturally-reproducing-patented-organisms/

- Enforceability of Medical Procedure Patents Under 35 U.S.C. § 287(c) | Oblon Life Science, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.lifesciencesipblog.com/enforceability-of-medical-procedure-patents-under-35-usc-287c

- Patent Infringement and Experimental Use Under the Hatch-Waxman Act: Current Issues – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R42354.html

- The Safe Harbor for FDA Submissions Expands: Did the Federal Circuit Reverse Course? | Insights | Jones Day, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2012/08/the-safe-harbor-for-fda-submissions-expands-did-the-federal-circuit-reverse-course

- Safe Harbor Provision of 35 USC 271e1 Implications of Intent and Continued Use, accessed December 19, 2025, https://ktslaw.com/en/Blog/fda/2018/9/Safe-Harbor-Provision-of-35-USC-271e1-Implications-of-Intent-and-Continued-Use

- Legal Battles Intensify: Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Lawsuits …, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/legal-battles-intensify-pharmaceutical-manufacturers-lawsuits-targeting-compounding-pharmacies

- Lilly, Novo Nordisk battle surge in copycat weight-loss drugs amid safety concerns, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/lilly-novo-nordisk-battle-surge-in-copycat-weight-loss-drugs-amid-safety-concerns/

- How Drug Shortages Spur Drug Compounding – RedSail Technologies, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.redsailtechnologies.com/blog/how-drug-shortages-spur-drug-compounding

- Compounding when Drugs are on FDA’s Drug Shortages List, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/compounding-when-drugs-are-fdas-drug-shortages-list

- Allowing Compounding Pharmacies to Address Drug Shortages – Mercatus Center, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/allowing-compounding-pharmacies-address-drug-shortages

- Eli Lilly Strikes Back Against Pharmacy Compounders and Telehealth Platforms | Insights, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/06/eli-lilly-strikes-back-against-pharmacy-compounders-and-telehealth

- Major Update on GLP-1 Litigation involving Compounding Pharmacies, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.bipc.com/major-update-on-glp-1-litigation-involving-compounding-pharmacies

- Novo Nordisk Settles Ozempic Patent Case – CHIP LAW GROUP, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.chiplawgroup.com/novo-nordisk-settles-ozempic-patent-case/

- GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Drug Litigation Overview and Trends – Foley & Lardner LLP, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.foley.com/insights/publications/2025/04/glp-1-receptor-agonists-drug-litigation-overview-trends/

- Compounding and GLP-1s: What To Expect When GLP-1 Drugs Are Removed From FDA’s Drug Shortage List | Insights | Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2024/12/compounding-and-glp1s-what-to-expect

- The Gray Zone: How 503B Pharmacies Navigate the Intersection of FDA Regulation and Drug Patents – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/the-gray-zone-how-503b-pharmacies-navigate-the-intersection-of-fda-regulation-and-drug-patents/

- Conducting a Biopharmaceutical Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis: Strategies for Efficient and Robust Results – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/conducting-a-biopharmaceutical-freedom-to-operate-fto-analysis-strategies-for-efficient-and-robust-results/

- 52.227-3 Patent Indemnity. – Acquisition.GOV, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.acquisition.gov/far/52.227-3

- A Pharma Exec’s Guide to Preliminary Freedom-to-Operate Analysis – DrugPatentWatch, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/a-pharma-execs-guide-to-preliminary-freedom-to-operate-analysis/

- How to Conduct a Drug Patent FTO Search: A Strategic and Tactical Guide to Pharmaceutical Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/how-to-conduct-a-drug-patent-fto-search/

- IP Indemnification Provisions Implicating Multiple Suppliers – Mayer Brown, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.mayerbrown.com/-/media/files/news/2016/08/ground-satellite-litigation-ip-indemnification-pro/files/f_bloch-acc_docket_september_2016/fileattachment/f_bloch-acc_docket_september_2016.pdf

- Compounding Pharmacy Market worth $19.41 billion by 2030 – MarketsandMarkets, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/PressReleases/compounding-pharmacy.asp

- The Profitability of a Compounding Pharmacy – THE PCCA BLOG, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.pccarx.com/Blog/the-profitability-of-a-compounding-pharmacy

- A framework for categorizing and analyzing prescription drug pricing reform options, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-framework-for-categorizing-and-analyzing-prescription-drug-pricing-reform-options/