The Valuator’s Teacup: Why Pharma Forecasting Is a High-Stakes Riddle

The Fundamental Challenge of Pharmaceutical Valuation

The pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors operate under a unique set of economic principles that can make traditional financial valuation models seem woefully inadequate. For an analyst accustomed to the relatively predictable cash flows of a mature manufacturing or retail business, the biopharma landscape is a high-stakes labyrinth of scientific uncertainty, regulatory hurdles, and intellectual property complexities. It is, as some have noted, like trying to measure the ocean with a teacup.1

This profound uncertainty is not merely a theoretical construct; it is a tangible, measurable financial reality. The average cost of bringing a single new prescription drug to market is an estimated $2.6 billion, a staggering figure that includes not only the direct costs of successful development but also the financial burden of numerous failed drug candidates.1 The statistics are stark: over 90% of drugs that enter clinical trials fail to make it to market. The sunk costs associated with these failures are immense, with a single failed Phase III trial alone estimated to cost between $200 million and $500 million.1 These are investments that, once made, cannot be recovered. The inherent “go/no-go” dynamic of clinical development creates dramatic valuation discontinuities. A single clinical trial result has the power to double or halve a company’s market value overnight, a level of volatility that standard financial models, built on more predictable revenue streams, are simply not designed to accommodate.1

To navigate this landscape, specialized valuation approaches are required. Risk-adjusted net present value (rNPV) models, for instance, explicitly account for the probabilities of success and failure at each development stage. This methodology transforms a static valuation into a dynamic, forward-looking forecast that evolves with each new piece of data. The valuation of a hypothetical drug candidate, for example, can jump dramatically from $45.8 million at Phase I to $312.1 million at the time of New Drug Application (NDA) submission, reflecting the progressive de-risking of the asset.1 This fluid, probabilistic nature of value is the first major hurdle for anyone seeking to accurately forecast a pharmaceutical company’s future.

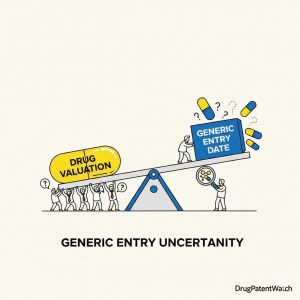

The Patent Cliff: A Clear and Present Danger

If scientific and regulatory risks define the early life of a drug, intellectual property (IP) risk dictates its commercial endgame. The entire high-risk, high-cost R&D gamble is predicated on the temporary monopoly power conferred by patent protection. A company’s patent portfolio, therefore, is not a legal afterthought but the most critical forward-looking indicator of its financial future.2 The value of a drug’s revenue stream is directly and inseparably tied to the remaining life and defensive strength of its patents.1

This reality is brought into sharp focus by the impending “patent cliff,” a major competitive threat where revenues for blockbuster drugs can plummet by as much as 79% after lower-cost generic rivals enter the market.3 This is not a distant, abstract threat. Analysts project that between now and 2030, more than $200 billion in annual pharmaceutical revenue is at risk due to expiring patents.2 A company’s balance sheet is, by its very nature, a historical document. It tells a story of what has already happened. In a sector where a single product can generate a disproportionate amount of revenue, and its patent-protected life is the sole mechanism for recouping a multi-billion dollar investment, the future is not found in the quarterly earnings report. It is found in the patent data, which provides a transparent and factual snapshot of where a company is investing its innovation efforts and when its core revenue streams are most vulnerable.4 The ability to accurately model the timing and magnitude of this inevitable revenue erosion is a direct determinant of valuation accuracy and a critical source of competitive intelligence.

The severity of this revenue erosion is not uniform; it is directly correlated with the intensity of generic competition. The initial entry of a single generic competitor, for instance, leads to a significant but contained price drop. As the number of competitors increases, the pressure on pricing intensifies dramatically, leading to a precipitous decline in both price and brand market share.

| Number of Competitors | Price Decline (Relative to Pre-Generic Price) |

| 1 | Modest decline, often less than 20% |

| 3 | Approximately 20% decline |

| 10 or more | 70% to 80% decline |

| Multiple (>1) | 50% to 80% decline in the first year |

As the table illustrates, the price of a drug in a market with ten or more generic competitors can be reduced by 70% to 80% relative to its pre-generic entry price, a far more severe erosion than in a market with only two or three players.5 This demonstrates that forecasting is not simply a matter of predicting

if a generic will enter, but rather when and how many will follow.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Grand Bargain on a Billion-Dollar Battlefield

In the United States, the dynamics of generic entry are governed by a complex and highly strategic legislative framework: the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, universally known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. This landmark legislation was designed to strike a delicate balance between two seemingly contradictory objectives: incentivizing pharmaceutical innovation through patent protection while simultaneously promoting generic competition to make medications more affordable for consumers.6 This grand bargain created a new and specialized litigation pathway—the Paragraph IV (PIV) challenge—that has become a central determinant of pharmaceutical valuation.

The Mechanics of a Paragraph IV Challenge

A Paragraph IV certification represents a direct and audacious challenge to the validity of a brand manufacturer’s intellectual property.6 A generic drug applicant, when filing its Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), must make a certification for each patent listed in the FDA’s “Orange Book” for the brand-name drug it seeks to copy.6 A Paragraph IV certification is a bold assertion that, in the generic company’s opinion, the brand patent is “invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed” by the proposed generic product.6

This bold assertion is not merely a statement; it is a “technical act of patent infringement” under U.S. law, designed to force a legal confrontation.6 Within 20 days of the FDA deeming the ANDA “substantially complete,” the generic applicant must send a detailed “notice letter” to the brand company and any patent holders.6 This letter must provide a detailed factual and legal basis for the challenge, setting the stage for a high-stakes legal battle.6 For a valuation professional, the presence or absence of a PIV filing—and the timing of that filing, which typically occurs a median of 5.2 years after the brand drug’s FDA approval—is a critical, predictable signal of impending market competition.11

The 30-Month Stay: A Strategic Shield or an Illusory Delay?

Upon receiving a Paragraph IV notice letter, the brand manufacturer has a 45-day window to initiate a patent infringement lawsuit.6 If a lawsuit is filed within this window, an automatic 30-month regulatory stay is triggered, during which the FDA generally cannot grant final approval to the generic application.6 This provision provides brand manufacturers with a predictable window of continued exclusivity—approximately two and a half years—during which their patent dispute can be resolved.6 This stay is a critical component of product lifecycle management, as it allows brand companies to maximize revenue from mature products and execute defensive strategies.6

However, the stay is not an impenetrable shield. Research suggests that the 30-month stay may not be as determinative of generic entry timing as is commonly assumed, as other factors, such as additional patents, manufacturing challenges, or settlement agreements, often play a more significant role.6 This means that the valuation impact of a PIV filing is not just about the stay’s duration, but about the brand company’s ability to successfully execute defensive tactics during that precious window. These strategies can include launching an authorized generic, transitioning patients to next-generation products, or reinforcing their patent “thicket” with additional formulation or method-of-use patents.2

The 180-Day Exclusivity: The Prize for the First-to-File

To incentivize these patent challenges, the Hatch-Waxman Act offers a powerful reward: the first generic company to file a “substantially complete” ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification is eligible for 180 days of market exclusivity upon launch.6 This creates a temporary duopoly between the brand and the first generic entrant, as the FDA will not approve any subsequent generic applications for the same product during this six-month period.6

This exclusivity period is the financial jackpot of the generic business model. With only one other competitor on the market, the first generic entrant can price its product at a significant but moderate discount to the brand—typically 15-25% below brand pricing.6 This yields substantially higher margins than in the post-exclusivity market, where multiple generic competitors may drive prices down by 80-90% below the original brand price.6 For a blockbuster drug, the financial reward of this exclusivity can be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, a powerful motivator that explains the aggressive pursuit of first-to-file opportunities by generic manufacturers.6 The high success rate of these challenges, which climbs to 76% when settlements and dropped cases are included, shows that the calculated risk of litigation is often worth the potential payoff.6

| Phase of a Paragraph IV Challenge | Key Event | Timeline | Strategic Implication |

| The Filing | Generic files an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification to challenge a brand patent. | N/A | Signals the generic’s intent to enter the market; a key signal for investors and analysts. |

| The Notice | Generic sends a detailed notice letter to the brand company and patent holder. | Within 20 days of a “substantially complete” ANDA filing. | The brand company’s 45-day defense window begins, triggering litigation if a suit is filed. |

| The Litigation Trigger | Brand company files a patent infringement lawsuit in response to the notice letter. | Within 45 days of receiving the notice letter. | Triggers the automatic 30-month stay on FDA approval for the generic. |

| The Regulatory Stay | The FDA cannot grant final approval to the generic ANDA. | 30-month period or until a court decision is rendered, whichever comes first. | Provides a predictable, two-and-a-half-year window of continued exclusivity for the brand company. |

| The Outcome | Litigation is resolved through a court decision or settlement. | Variable (litigation can last for years). | Determines the timing of generic market entry and the brand’s future revenue stream. |

| The Reward | The first-to-file generic company launches its product after a favorable outcome. | 180-day market exclusivity period begins. | Creates a duopoly and a highly profitable period for the first generic entrant. |

The Financial Crucible: Deconstructing the Costs and Stakes of Litigation

The Paragraph IV process is not a low-cost affair. For both innovator and generic companies, engaging in this structured legal conflict carries substantial financial and operational burdens. A comprehensive valuation must account for these costs, which come in both highly visible and less obvious forms.

Visible Costs: The Multi-Million-Dollar Tab

The direct, tangible costs of pharmaceutical patent litigation are staggering. The average cost of a single patent dispute can range from $1 million to $5 million.16 For high-stakes cases with over $25 million at risk, litigation costs can exceed $4 million.17 The financial burden is not linear and is driven by several key factors. Legal fees are, without question, the single largest component of any litigation budget, with rates for elite attorneys often running well over $1,000 per hour.10

Expert witness fees are another significant cost driver. In a complex pharmaceutical case, expert witnesses—often PhD-level scientists and economists—are indispensable for explaining the intricate scientific and financial concepts to a judge. These fees can easily run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars per expert.10 Finally, the discovery phase is a notorious cost driver, involving the collection, review, and production of millions of pages of internal documents, lab notebooks, and regulatory filings.10 The technology and vendor costs for managing this immense volume of e-discovery can escalate into millions of dollars.10 This high cost of litigation is not just a financial burden; it is a structural barrier to entry that can effectively stifle competition from smaller, less-capitalized challengers, potentially consolidating market power among a few large players.10

Invisible Costs: The Erosion of Opportunity and Human Capital

While the direct costs of litigation are formidable, the most damaging costs are often those that do not appear on a legal invoice. These “invisible costs” are reflected in lost opportunities, diminished innovation, and eroded shareholder value.10

The diversion of key personnel is perhaps the most significant indirect cost. A patent lawsuit is not fought solely by outside lawyers; it requires the intense involvement of top scientists, R&D executives, and other key technical personnel. These individuals are pulled away from their core responsibilities—the very work of discovering and developing the next generation of life-saving medicines—to answer interrogatories, sit for depositions, and prepare for trial.10 The time and energy spent fighting over an existing product are not spent on inventing the next one. This diversion represents a massive opportunity cost, a type of “tax” on innovation that is a critical, yet often-overlooked, factor in long-term corporate valuation.18

Furthermore, litigation strains the relationship between the parties and may jeopardize cooperation on other fronts. For financially weaker firms, the risk of a lost case and its associated damages can cause credit costs to soar.18 Even without a preliminary injunction, customers of an alleged infringer may stop buying their product due to the risk that it will be withdrawn from the market, leading to a loss of sales and goodwill.18

The Financial Stakes: Averages and Anomalies

The stakes of this litigation are astronomical. Research shows that the average stakes for a brand firm in a PIV case are an estimated $4.3 billion, while the average stakes for a generic firm are approximately $204.3 million (in 2010 dollars).19 This massive difference in stakes highlights the immense financial payoff that a brand firm may reap by preserving its monopoly power.19

This is a market where every win and loss is a public event that can be tracked in real-time. Event study analysis of stock market valuations following litigation decisions shows a direct correlation between legal outcomes and corporate value. For a brand firm, a patent win is associated with an average value increase of about 2.1%, while a loss is associated with an average value decrease of 2.4%.19

| Party | Average Stakes (in 2010 USD) | Average Value Increase (upon a win) | Average Value Decrease (upon a loss) |

| Brand Firm | $4.3 Billion | 2.1% | 2.4% |

| Generic Firm | $204.3 Million | 3.1% | 1.6% |

The discrepancy between the total stakes (in the billions) and the stock market’s reaction (a few percentage points) is highly telling. It suggests that the market has already “priced in” a probabilistic outcome for the litigation. The stock price movement upon a decision is not a reflection of the total value but rather the market’s recalibration of its belief about the probability of success. The true financial alpha, therefore, lies not in simply knowing the outcome, but in having a more accurate probabilistic forecast than the market consensus.19

Antitrust on the Horizon: The Evolving Landscape of Pay-for-Delay Settlements

In the high-stakes world of Hatch-Waxman litigation, the most common outcome is not a court decision but a settlement. For decades, a specific type of settlement known as a “pay-for-delay” or “reverse payment” agreement became increasingly common.20 In these agreements, the brand company, in a reversal of the typical flow of money, pays the generic challenger to drop its suit and stay off the market for a specified period.7 These deals have been widely criticized as anticompetitive, as they can effectively nullify the procompetitive intent of the Hatch-Waxman Act.21

The Watershed Moment: The FTC v. Actavis Decision

The legality of these agreements was a subject of intense debate and conflicting rulings among federal circuit courts until the Supreme Court’s landmark 2013 decision in FTC v. Actavis.23 In a watershed ruling, the court held that while these settlements were not

per se illegal, they were subject to antitrust scrutiny under the “rule of reason”.23 The court found that “large and unjustified” payments to generic companies could be unlawful and that a settlement’s potential for genuine adverse effects on competition must be measured against the “procompetitive” policies of antitrust law.23

The decision, while hailed as a victory for antitrust regulators, was deliberately opaque about the parameters of what constitutes a “large and unjustified” payment.24 As Chief Justice Roberts famously predicted in his dissent, the ambiguity has left lower courts struggling to apply a clear and consistent analytical framework.24 The legal uncertainty left by

Actavis has created a new layer of complexity and risk, pushing the industry to evolve its settlement structures away from explicit cash payments and into more creative, and harder-to-scrutinize, “in-kind” payments.27

Beyond Cash: The Rise of In-Kind Settlements

In the wake of Actavis, explicit reverse payments, beyond compensation for saved litigation expenses, have become less common.27 In their place, settlement agreements have grown increasingly complex, incorporating a variety of non-cash value transfers that are now the subject of intense antitrust scrutiny.27 These “in-kind” payments can include:

- “No Authorized Generic” (No-AG) Commitments: The brand company agrees not to launch its own authorized generic to compete with the first-to-file generic during the 180-day exclusivity period.27

- Declining Royalty Structures: The brand and generic agree to a royalty arrangement where the generic’s payments are eliminated or reduced if the brand launches an authorized generic.27

- Quantity Restrictions: The settlement restricts the quantity of product the generic can sell for a period of time, which, if sufficiently strict, can alter market dynamics and maintain supracompetitive prices.27

The financial implications of these non-cash terms are significant and must be precisely valued. A “no authorized generic” commitment, for example, is not an abstract legal term; it is a direct, quantifiable financial benefit that allows the first-to-file generic to retain a larger market share and higher margins during its 180-day exclusivity window.27 By financially modeling these terms, analysts can accurately forecast the profitability of a settlement for both parties. The evolution of these practices demonstrates a clear cause-and-effect relationship: legal and regulatory scrutiny of one type of behavior (cash payments) leads to an evolution of the practice into a more complex, but still financially quantifiable, form (in-kind payments).27

Case in Point: Lessons from the Frontlines of Litigation

The theoretical framework of Hatch-Waxman litigation is best understood through real-world case studies, where the strategic choices of brand and generic firms have shaped multibillion-dollar outcomes.

The War for Lipitor: Pfizer’s Defensive Masterclass

Few drugs have been as valuable as Pfizer’s cholesterol-lowering medication, Lipitor, which generated over $130 billion in sales before it lost patent protection.2 The battle to protect its market exclusivity serves as a masterclass in aggressive, multi-pronged defensive strategy. In what was dubbed the “180-day war,” Pfizer faced an onslaught of generic challenges. Its defensive playbook included an unprecedented rebate offensive and the strategic use of an authorized generic (AG).2

An authorized generic is a brand-name drug that is marketed as a generic by a subsidiary of the brand company or a third party.6 While the launch of an AG cannibalizes the brand’s own sales, it also drastically reduces the potential profitability of the first-to-file generic during the lucrative 180-day exclusivity period.6 In fact, an authorized generic competing with a single generic can reduce the generic’s revenues by an average of 50%.28 This strategy not only mitigates revenue loss for the brand but also serves as a powerful deterrent to other generic entrants, who see the potential for a less profitable, hyper-competitive market from day one. This proactive defensive measure must be meticulously factored into any valuation model.

Humira’s Iron Grip: A Biosimilar Battle with a Patent Thicket

The story of AbbVie’s Humira, a blockbuster with over $20 billion in annual sales, is a testament to the power of a layered IP defense.29 AbbVie maintained a near-monopoly on the U.S. market for years by constructing a formidable “patent thicket” of over 60 patents that covered every conceivable aspect of the drug—from the active compound to its formulation, method-of-use, and manufacturing process.29

This isn’t just a legal defense; it’s a financial moat that preserves a multibillion-dollar revenue stream. While the individual patents may be weak, their sheer number and overlapping nature create a logistical and financial nightmare for any challenger, forcing them into a strategic dance and lengthy litigation.29 This multi-front battle ultimately led to a series of settlements that granted AbbVie years of additional market exclusivity, even as biosimilars were already available in Europe.29 The valuation of AbbVie’s IP is therefore not just a sum of its individual patents, but the collective deterrent effect of the entire portfolio, a defense that transforms a drug’s IP from a single asset into a fortress.

Copaxone’s Fate: The High Cost of Abusive Practices

The case of Teva’s Copaxone serves as a powerful cautionary tale. While aggressive litigation and lifecycle management are core to brand strategy, these tactics are not without legal and regulatory risk. The European Commission fined Teva €462.6 million for abusing its dominant position in the market for glatiramer acetate, the active ingredient in Copaxone.12 The abuses were found to include “product hopping,” where Teva pre-emptively converted patients from a daily dose to a three-times-a-week formulation to extend patent protection and delay competition.12 The company was also found to have misused divisional patents to create a “divisionals game” that forced generics to repeatedly challenge patents with “marginal” differences.12

The massive fine represents a direct, quantifiable financial liability that undermines the very revenue stream the company was trying to protect. This demonstrates that a valuation must not only consider a company’s patent portfolio but also the legal and regulatory risks associated with its strategic defense of that portfolio. Aggressive tactics, when deemed anticompetitive, can transform a short-term market advantage into a long-term corporate liability.

“A patent is not just a legal document; it is the financial bedrock of the entire industry, the sole mechanism that allows companies to recoup the monumental, high-risk investments required to bring a new medicine from a laboratory bench to a patient’s bedside.” 10

From Data to Alpha: Integrating Patent Intelligence into Corporate Strategy

The traditional approach to intellectual property is reactive: a company files a patent, and then it defends it when challenged. In the modern, data-rich pharmaceutical landscape, a new paradigm is emerging—one that is proactive and data-driven. The most successful teams understand that patent data is not just a legal document but a source of strategic, value-creating business intelligence.

A New Toolkit for R&D and BD Teams: Leveraging Platforms Like DrugPatentWatch

The public availability of patent data provides a concrete basis for evaluating a competitor’s R&D efforts and future market moves.4 The challenge is to transform this raw information, often overwhelming in its volume, into actionable insights. This is where specialized platforms like

DrugPatentWatch come into play.

DrugPatentWatch offers a suite of tools that provide deep insights into global drug patents, litigation histories, and exclusivity status.33 This enables teams to move from a reactive defense to a proactive offense. R&D teams, for instance, can analyze a competitor’s patent filings to predict their future pipeline and strategic priorities.4 By tracking the rate at which a competitor is filing patents in a specific technology area, a company can gauge the intensity of their R&D efforts and adjust its own innovation roadmap accordingly.4

For business development teams, this intelligence is invaluable. They can use the platform to identify drugs with weak patents or looming expiration dates, scouting for licensing, acquisition, or partnership targets.33 This strategic use of data turns a legal compliance function into a core business development capability, allowing companies to anticipate market entry and mitigate financial risk.

Proactive Strategies for Innovators: Building a Litigation-Resistant Fortress

The high costs of litigation and the severe financial impact of a lost case make the quality of a patent portfolio paramount.19 A litigation-resistant fortress is not built with a single, broad patent but with a multi-layered claim strategy. This includes broad independent claims to provide the widest possible scope of protection for the core invention, as well as narrow dependent claims that build upon the independent claims with specific limitations.10

A robust defensive strategy also involves building a “patent thicket” with secondary patents, such as method-of-use and formulation patents.2 These patents can be used to extend market exclusivity and deter generic challengers, who must challenge each patent individually.3 Ultimately, the best defense is a great offense. Proactive pipeline development and strategic mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are essential for replacing revenue from mature products and maintaining long-term growth.2

Offensive Strategies for Generics: Identifying and Exploiting Weak Patents

Generic firms have their own strategic playbook, one predicated on identifying and exploiting weaknesses in a brand company’s IP portfolio. The Hatch-Waxman Act effectively deputizes generic companies to act as “private attorneys general” or “sheriffs,” scrutinizing and challenging potentially weak or invalid patents that stand in the way of competition.9

This involves conducting a meticulous, early-stage patent analysis to identify patents that are vulnerable to challenges based on prior art, obviousness, or non-infringement arguments.13 The

DrugPatentWatch platform, for instance, provides a transparent record of patents and litigation histories that enables generic companies to identify market entry opportunities and inform portfolio management decisions.33 The existence of a streamlined, lower-cost process like Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) also significantly lowers the barrier to entry for generic challengers, offering a faster and cheaper alternative to traditional court litigation with a lower burden of proof.2 This makes a multi-pronged attack on a brand’s IP portfolio—in both district court and at the PTAB—a more viable and cost-effective strategy.

Key Takeaways

The fundamental challenge of pharmaceutical valuation lies in its inherent uncertainty, driven by long R&D cycles and the binary outcomes of clinical trials. However, generic entry uncertainty, while a significant pain point, is not an abstract risk but a quantifiable pain point that can be modeled, forecast, and managed. The key lies in transforming a reactive IP defense into a proactive, data-driven strategy.

- Intellectual Property as a Financial Metric: In a sector where a single drug can define a company’s financial future, the patent portfolio is the most critical forward-looking indicator of value. The impending patent cliff is a predictable, existential threat that can and must be precisely mapped.

- The Hatch-Waxman Act is a Litigation Engine: The PIV process is a structured legal conflict with predictable timelines and powerful financial incentives. Understanding these mechanics is foundational for anyone involved in valuation, R&D, or business development.

- Costs Extend Beyond the Legal Bill: The high costs of litigation are not merely a financial burden; they are a structural barrier to entry for smaller firms and a massive opportunity cost for all companies, diverting key personnel and eroding long-term innovation.

- Antitrust is a Critical Variable: The legal landscape is evolving. In the post-Actavis era, “in-kind” payments in settlement agreements are now the subject of antitrust scrutiny and must be financially modeled. These non-cash terms are a new frontier of risk and opportunity.

- Data is the Source of Alpha: The most sophisticated teams understand that patent data is a source of competitive intelligence. By leveraging platforms like DrugPatentWatch, companies can move beyond reactive defense to proactively anticipate market entry, identify strategic opportunities, and mitigate financial risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the “generics paradox,” and how does it influence brand drug pricing after patent expiration?

The “generics paradox” refers to a phenomenon observed in some markets, particularly the U.S., where the price of an originator brand drug does not decline significantly after the first generic competitor appears; in some cases, it may even increase.36 This appears to contradict the principle of competition leading to lower prices. The paradox is a short-term phenomenon. It can occur because the first generic entrant, granted 180-day exclusivity, can price its product at a high-margin, moderate discount to the brand, as there is little competition.6 The brand drug’s price may not fall because it still commands a significant share of the market, which is often composed of patients, physicians, and payers who are loyal or resistant to change.36 However, once multiple generic competitors enter the market after the exclusivity period, prices for both the generic and brand products will plummet, with prices falling by 70% to 80% relative to the pre-generic price in markets with ten or more competitors.5

How do “in-kind” payments in settlement agreements affect pharmaceutical valuations, and what is their legal status?

In the wake of the FTC v. Actavis Supreme Court decision, which subjected “pay-for-delay” settlements to antitrust scrutiny, explicit cash payments to generics have become less common.27 They have been replaced by more complex “in-kind” payments, such as a brand company’s commitment not to launch an authorized generic, or a declining royalty structure.27 These non-cash terms have a direct, quantifiable financial value. For a generic company, a “no authorized generic” commitment, for example, can preserve a larger market share and higher margins during its 180-day exclusivity period, an effect that can be modeled and valued.27 These agreements are not immune from antitrust scrutiny, as the FTC continues to actively police them to ensure they do not constitute an anticompetitive transfer of value that harms consumers by delaying generic entry.27

What is the strategic difference between a compound patent and a method-of-use patent, and why are both critical for a strong valuation?

A compound patent, often the most valuable, protects the active chemical ingredient of a drug and provides the broadest and most fundamental layer of protection.30 A method-of-use patent, in contrast, protects a specific way of using the drug to treat a particular condition, rather than the drug itself.30 Both are critical for a strong valuation because they enable a brand company to construct a “patent thicket”—a layered defense of numerous, overlapping patents.2 While the core compound patent may expire, secondary patents, such as those protecting specific formulations or methods of use, can extend a drug’s overall market exclusivity. This creates a formidable barrier to entry that forces generic challengers into a more complex, costly, and lengthy legal battle to clear the path for their product.29

Beyond legal fees, what are the most significant indirect costs of Paragraph IV litigation, and how do they impact a company’s long-term value?

The most significant indirect costs of Paragraph IV litigation are the diversion of key personnel and the erosion of corporate opportunity.10 A patent lawsuit is not a self-contained legal event; it requires the intense involvement of top scientists, R&D executives, and other key personnel who are pulled away from core business functions like drug development to handle discovery, depositions, and trial preparation.10 This represents a massive opportunity cost, as the time and energy spent fighting over an existing product are not being used to innovate the next one. This “tax” on innovation can have a more damaging impact on a company’s long-term value than the direct legal bill, as it can slow the development of future revenue streams and weaken the company’s competitive position.10

How can a company use a platform like DrugPatentWatch to anticipate market entry and mitigate financial risk?

A company can use a platform like DrugPatentWatch to transform a reactive IP strategy into a proactive, data-driven one.33 The platform provides a transparent source of information on global drug patents, litigation histories, and patent expiration dates.33 By tracking Paragraph IV filings and their outcomes, a company’s IP team can work with its business development and financial forecasting teams to anticipate the earliest possible date of generic entry for a competitor’s drug.33 This allows them to de-risk their portfolio, identify market entry opportunities, inform portfolio management decisions, and even prevent the overstocking of off-patent drugs.33 For a generic manufacturer, this intelligence can be used to identify drugs with weak patents or looming expiration dates, allowing them to scout for potential opportunities and prepare for a timely, first-to-file challenge.

Works cited

- Valuation of Pharmaceutical Companies: A Comprehensive …, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/valuation-of-pharma-companies-5-key-considerations/

- Transforming Drug Patent Data into Financial Alpha – DrugPatentWatch, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/transforming-drug-patent-data-into-financial-alpha/

- The Economics of the Pharmaceutical Sector: Innovation, Competition, and Patent Policy, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-economics-of-the-pharmaceutical-sector-innovation-competition-and-patent-policy/

- The Role of Patent Analytics in Competitive Intelligence – PatentPC, accessed September 17, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/the-role-of-patent-analytics-in-competitive-intelligence

- aspe.hhs.gov, accessed September 17, 2025, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/510e964dc7b7f00763a7f8a1dbc5ae7b/aspe-ib-generic-drugs-competition.pdf

- What Every Pharma Executive Needs to Know About Paragraph IV …, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-every-pharma-executive-needs-to-know-about-paragraph-iv-challenges/

- Pharmaceutical Patents, Paragraph IV, and Pay-for-Delay – Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of, accessed September 17, 2025, https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1024&context=ipbrief

- Patent Certifications and Suitability Petitions – FDA, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/patent-certifications-and-suitability-petitions

- What to Expect from Drug Patent Litigation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/what-to-expect-from-drug-patent-litigation/

- Managing Drug Patent Litigation Costs: A Strategic Playbook for the Pharmaceutical C-Suite, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/managing-drug-patent-litigation-costs/

- The timing of 30‐month stay expirations and generic entry: A cohort study of first generics, 2013–2020, accessed September 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8504843/

- European Commission Fines Teva €462.6 Million for Misusing Divisional patents and Disparaging Generic Competitors in the Copaxone Market – McDermott Will & Emery, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.mwe.com/insights/european-commission-fines-teva-e462-6-million-for-misusing-divisional-patents-and-disparaging-generic-competitors-in-the-copaxone-market/

- Paragraph IV (Para IV) Filing | Overview & Strategies – Pharma Lesson, accessed September 17, 2025, https://pharmalesson.com/paragraph-iv-para-iv-filing-overview-strategies/

- You Don’t Need to Win the Patent — You Need to Win the Market: What No One Tells You About Winning Drug Patent Challenges – DrugPatentWatch – Transform Data into Market Domination, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/you-dont-need-to-win-the-patent-you-need-to-win-the-market-what-no-one-tells-you-about-winning-drug-patent-challenges/

- Predicting patent challenges for small-molecule drugs: A cross-sectional study | PLOS Medicine – Research journals, accessed September 17, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1004540

- Pharmaceutical Firms Face $1 Million to $5 Million Patent Litigation Costs – GeneOnline, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.geneonline.com/pharmaceutical-firms-face-1-million-to-5-million-patent-litigation-costs/

- The Cost of Patent Litigation: Key Statistics – PatentPC, accessed September 17, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/the-cost-of-patent-litigation-key-statistics

- The Private Costs of Patent Litigation | Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law, accessed September 17, 2025, https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/context/faculty_scholarship/article/2389/viewcontent/The_Private_Costs_of_Patent_Litigation_pub.pdf

- The Distribution of Surplus in the US Pharmaceutical Industry …, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/707407

- Pay for Delay | Federal Trade Commission, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/competition-enforcement/pay-delay

- Reverse payment patent settlement – Wikipedia, accessed September 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverse_payment_patent_settlement

- Paying for Delay: Pharmaceutical Patent Settlement as a Regulatory Design Problem, accessed September 17, 2025, https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/contract_economic_organization/11/

- FTC v. Actavis, Inc. – Wikipedia, accessed September 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FTC_v._Actavis,_Inc.

- A Decade of FTC v. Actavis: The Reverse Payment Framework Is Older, But Are Courts Wiser in Applying It? – American Bar Association, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/antitrust/journal/86/issue-2/decade-of-ftc-v-actavis.pdf

- Unprecedented State Law on Pharmaceutical “Reverse Payments” Goes Into Effect, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.wilmerhale.com/en/insights/client-alerts/20200108-unprecedented-state-law-on-pharmaceutical-reverse-payments-goes-into-effect

- A Decade of FTC v. Actavis: The Reverse Payment Framework Is Older, but Are Courts Wiser in Applying It | White & Case LLP, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/decade-ftc-v-actavis-reverse-payment-framework-older-are-courts-wiser-applying

- Reverse Payments: From Cash to Quantity Restrictions and Other Possibilities, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/competition-matters/2025/01/reverse-payments-cash-quantity-restrictions-other-possibilities

- Should We Settle? Considerations For Generic Companies Before Settling Hatch-Waxman Litigation – Cantor Colburn, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.cantorcolburn.com/media/news/40_201110_Sept%202011%20Shoudl%20We%20Settle%20-%20Hatch-Waxman%20Litigation.pdf

- Settlement Opens Doors for Biosimilars of Abbvie’s Most Profitable Drug – BioSpace, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.biospace.com/settlement-opens-doors-for-biosimilars-of-abbvie-s-most-profitable-drug

- Patent Litigation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Key Considerations, accessed September 17, 2025, https://patentpc.com/blog/patent-litigation-in-the-pharmaceutical-industry-key-considerations

- Alvotech Resolves U.S. Patent and Trade Secret Disputes with AbbVie, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.alvotech.com/newsroom/alvotech-resolves-u.s.-patent-and-trade-secret-disputes

- 5 Ways to Predict Patent Litigation Outcomes – DrugPatentWatch, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/blog/5-ways-to-predict-patent-litigation-outcomes/

- Find Your Next Blockbuster – Biotech & Pharmaceutical patents, sales, drug prices, litigation – DrugPatentWatch, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.drugpatentwatch.com/about.php

- DrugPatentWatch | Software Reviews & Alternatives – Crozdesk, accessed September 17, 2025, https://crozdesk.com/software/drugpatentwatch

- 5 Ways To Improve Your Competitive Intelligence Using Patent Landscaping Analysis, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.greyb.com/blog/patent-analysis-for-competitive-advantage/

- Effects of Generic Entry on Market Shares and Prices of Originator Drugs: Evidence from Chinese Pharmaceutical Market – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed September 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12209137/